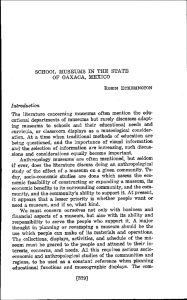

Pre-Columbian: Perspectives and Prospects MME LA BRUYÈRE: “Ma p’tite Jackie qu’est-ce que c’est, ton art précolombien?” JACKIE: “La civilisation américaine avant Christophe Colomb.” MME LA BRUYÈRE: “Ah, des histoires de negrès!” JACKIE: “Il n’y en avait pas encore!” MME LA BRUYÈRE: “Il y avait quoi alors?” JACKIE: “Mais des Indiens!” MME LA BRUYÈRE: “Évidemment, j’suis bete! Buffalo Bill!” Thus the character of Jackie, the sole representative of a younger generation in Jean Renoir’s film La reglè du jeu (The Rules of the Game, 1939), tries to define her field, Pre-Columbian art, to the aristocrat Madame de la Bruyère, whose racist conflation and confusion epitomizes entrenched traditions of social exclusion. The obscurity of Jackie’s subject, combined with her interlocutor’s inability to see, becomes a leitmotif of Renoir’s masterful critique of French society on the eve of World War II. The confusion over the use of the term, as well as its political baggage, continues to the present day. This unease over what the field is and where it belongs may have a direct bearing on future studies and opportunities, and thus calls for our attention. I begin this informal essay, therefore, with a consideration of the very term “Pre-Columbian,” and continue with a view of the field from the perspective of a scholar who has had the good fortune of enjoying professional positions at universities, research institutes, and most recently museums. As others will address the state of the field within the university system, including its museums, my focus will be on research institutes and independent museums. It is illuminating to begin by considering the historical use of the term “Pre-Columbian.” A brief inquiry using Google’s n-gram tool—the analysis of a contiguous sequence of words in a given corpus, in this case Google Books—shows that the term “Pre-Columbian art” appeared first in the late nineteenth century and did not come into wider use until around 1930.1 When the first 1. For a nuanced discussion of the historical use of the term “Pre-­ Columbian” in publications, academe, and in relation to the field of colonial ancient American works came into the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art—the first was acquired in 1877—they were referred to simply as “Mexican antiquities” or “Peruvian antiquities.” The introduction of the term “Pre-Columbian” seems to have arisen in conjunction with the concept of the world’s fair, itself a remarkable cultural phenomenon that emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century. In the United States, the civilizations of the ancient Americas were brought to broader public prominence through their persistent presence in world’s fairs and expositions, such as the 1884–85 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans; the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago; the 1904 Louisiana Purchase ­Exposition in St. Louis; the 1915 Panama-Pacific ­International ­Exposition in San Francisco; and the 1915 Panama-­California Exposition in San Diego. Of these, the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, celebrating the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, may have understandably been something of a driver for the term. A significant jump in its use occurred in 1940, perhaps related in part to the soft-power diplomatic efforts of Nelson Rockefeller and the Office of Inter-American Affairs.2 The OIAA was a wartime body devoted to public diplomacy across the Americas, and it fostered numerous exhibitions and other programs featuring Latin American art from Latin American art see Cecelia F. Klein, “Not Like Us and All the Same: Pre-Columbian Art History and the Construction of the Nonwest,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 42 (2002): 131–38. 2. On the Office of Inter-American Affairs see Holly Barnet-Sanchez, “The Necessity of Pre-Columbian Art in the United States: Appropriation and Transformations of Heritage, 1933–1945,” in Collecting the Pre-­Columbian Past, ed. Elizabeth Hill Boone (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1993), 177–207; Joanne Pillsbury, “The Panamerican: Nelson Rockefeller and the Arts of Ancient Latin America,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Summer 2014, 18–27. Further research on this subject and the history of Pre-Columbian exhibitions appears in Joanne Pillsbury and Miriam Doutriaux, “Incidents of Travel: Robert Woods Bliss and the Creation of the Maya Collection at Dumbarton Oaks,” in Ancient Maya Art at Dumbarton Oaks, ed. Joanne Pillsbury, Miriam Doutriaux, Reiko IshiharaBrito, and Alexandre Tokovinine (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2012), 1–25. Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture, Vol. 1, Number 1, pp. 121–127. Electronic ISSN: 2576-0947 © 2019 by The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of California Press’s Reprints and Permissions web page, http://www.ucpress.edu/journals.php?p=reprints. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/lavc.2019.000007f Dialogues 121 ancient to modern. The spirit of Pan-Americanism—the idea of strengthening political, economic, and cultural ties across the hemisphere—was a strong current circulating in diplomatic and business circles in the 1930s. Europe was perceived in the United States as on the downward slope of the inescapable arc of civilization, and with the onset of World War II, there was a palpable fear that European fascism would spread to Latin America. Rockefeller had faith that art, as a key component of diplomacy, could stem this tide. Crucially, Rockefeller argued fervently that Pre-­ Columbian works should be viewed as fine art, on par with Greek and Roman works. To his chagrin, the Met, after an auspicious start in the collection of ancient American art in the early years of its history, suspended acquisitions of Pre-Columbian sculpture in 1914 (although it still collected ancient Andean textiles) and sent most of its ancient American holdings across Central Park to the American Museum of Natural History on long-term loan. Other works from the Met’s collection went to the Brooklyn Museum, which had started collecting Native American art in 1903. Ancient American art did not return to the Met on a permanent basis until 1982. Robert Woods Bliss, also a diplomat and collector, was equally adamant that Pre-Columbian art should have a place in fine arts museums. Bliss’s collection of ancient American art was on display at the National Gallery of Art from 1947 until 1962, when it was transferred to its current home at Dumbarton Oaks, also in Washington, DC. Interestingly, the installation at the National Gallery was called Indigenous Arts of the Americas, a term Rockefeller, a half-generation younger than Bliss, also initially preferred. He became frustrated, however, with the fact that the public kept confusing “indigenous” with “indigent,” so he switched to “primitive,” ultimately naming his new museum in New York the Museum of Primitive Art. That rubric was widely used for some fifty years in the middle of the twentieth century to refer to the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas—essentially “other-than-Western” art outside of Asia. “Primitive art” follows a similar n-gram trajectory as “Pre-Columbian,” but with a steadier climb from 1920 to 1940, followed by a peak in 1970 and then a precipitous decline. When the staff and collections of the Museum of Primitive Art were incorporated into the Met in the late 1970s, the new department retained the name, but when the Rockefeller Wing opened in 1982, the galleries were dedicated to the “Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.” 122 latin ame r ican and latinx visual cultu r e The biggest increase in the use of the term “Pre-­ Columbian art” occurred in the decade between 1970 and 1980, with a peak in 1982 and a fairly steady decline after that. The decline is not necessarily related to the rise of alternative terms, such as “ancient American art,” which displays a lower, albeit longer and steadier n-gram. Such shifts undoubtedly reflect a rising disregard for the term “Pre-Columbian” as overly referential to European history and insensitive to the consequences of 1492 for the Indigenous populations of the Americas. But the decline of “Pre-Columbian” in the n-gram may also be conversely related to the 1982 peak. This period was a high-water mark for expansion in the humanities in the United States, manifested in a pronounced increase in the size of faculties at colleges and universities. The expansion of a professorate with an interest in ancient American art in institutions of higher learning led to increasingly specialized publications addressed to an audience of academics. Part of the decline in the use of the term is surely related to the fact that we can now produce books on topics such as scale in Inca art or the murals of Cacaxtla without feeling the need to include “Pre-Columbian” in the title. This trend toward specialization is also visible within the museum world. Instead of exhibitions on the arts of the Pre-Columbian Americas, we can now mount major international loan exhibitions on the art of the Wari, or the art of the Tiwanaku, or even works from a single city, such as the Teotihuacan exhibitions organized by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.3 Whatever the reasons for the decline of “Pre-Columbian” as a designation for the arts of the Americas before the arrival of Europeans—and the reasons are surely overdetermined—the steep drop in the use of the term certainly tracks with our own informal research while preparing the recent Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas exhibition.4 Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum the Getty Research 3. Susan E. Bergh, Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes (New York: Thames and Hudson; Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2012); Margaret YoungSánchez, ed., Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca (Denver: Denver Art Museum; Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004); Kathleen Berrin and Esther Pasztory, eds., Teotihuacan: Art from the City of the Gods (New York: Thames and Hudson; San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1993); Matthew Robb, ed., Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire (San F ­ rancisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Oakland: University of C ­ alifornia Press, 2017). 4. Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds., Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017). Institute in Los Angeles and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the exhibition was unusual in that it did not focus on a single culture from a single modern nation. My co-­curators, Timothy Potts and Kim Richter, and I sought to explore the development of goldworking across the Americas, from south to north, as it crossed paths with other materials such as jadeite and feathers—­materials then considered more precious than gold. In our own admittedly modest market surveys of a museumgoing public, it became abundantly clear that no one under fifty knew what the term “Pre-Columbian” meant. They were not so certain what “ancient American” meant, either, but they were intrigued enough by the first part of the title to come and figure it out. It is important to bear in mind that research in the field of Pre-Columbian art history—indeed art history in any field—is not limited to major research universities in the United States. The Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas in Mexico City, part of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, founded in 1936, has been a major center for advanced research in the visual arts, including Pre-­Columbian. In the United States, research institutes dedicated to art history, including the Center for Advanced Studies in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art (CASVA) and the Getty Research Institute (GRI), but also the more broadly humanistic Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections, have been major supporters of research in the arts of the ancient Americas. The research institutes have been, and remain, crucial players in the field, not only through fellowships and conferences, but also through fostering long-term research projects of the sort unlikely to be pursued within a university setting (I will soon explain why). Research institutes with concentrations on the arts of the ancient Americas are less common in Europe, but places such as the Sainsbury Research Unit for the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the University of East Anglia in England have had a sustained presence in the field. The contributions of research institutes to the study of ancient American art have been significant. Some, such as the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University (NYU), founded in 1932, are affiliated with universities, while others, such as CASVA, are part of, or sister institutions of, larger entities including museums. In terms of the study of ancient American art, the previously mentioned Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas was ahead of the pack in terms of its scholarly embrace of ancient American art. Its journal, Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, for example, has included since its inception in 1937 articles on subjects such as the sixteenth-century Relación de Michoacán, the Codex Cospi, and mural painting. A focus on ancient American art at some research institutes has been flickering at best, but three entities in particular have made notable efforts to incorporate studies of ancient American art: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, CASVA, and the GRI. Dumbarton Oaks, a research institute of Harvard University in Washington, DC, has been the preeminent center for the study of ancient American art since the late 1960s through a program of fellowships, symposia, publications, and other activities. CASVA has consistently engaged with ancient American art through fellowships, research professorships, and conferences since it was created in 1979. The GRI, founded six years later, has similarly welcomed scholars working on the ancient Americas from its inception. What often sets research institutes apart from universities is their ability to support major, long-term collaborative research projects involving teams of international scholars working together to produce reference works or other tools. In the field of ancient American art history these include CASVA’s Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies, 1530–1900, a three-volume work that overviews early modern and later sources for the study of the Incas and other Indigenous cultures of the Andean region of South America.5 The GRI has been producing not only major digital resources for art history in general, such as the Getty Research Portal, an international collaborative project making rare books and other research materials freely available, but also more specialized projects such as the ongoing Florentine Codex research initiative. Such projects—some spanning a decade or more, and involving hundreds of scholars in many c­ ountries—would be cumbersome or impossible to produce within a university setting. As the abovementioned case of the Metropolitan Museum of Art illustrates, the status of Pre-Columbian objects as fine art has been neither universally embraced nor constant. The Met had amassed several thousand works 5. Joanne Pillsbury, ed., Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies, 1530–1900, 3 vols. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art; Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008). Translated and revised as Joanne ­Pillsbury, ed., Fuentes documentales para los estudios andinos, 1530–1900, 3 vols. (Lima: Fondo Editorial, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2016). Dialogues 123 of ancient American sculpture by 1914, the year in which it decided Pre-Columbian sculpture did not have a place on Fifth Avenue. The Met’s decision was due, in part, to challenges from other players in New York, including George Heye’s Museum of the American Indian, which began assembling a massive Native American and Pre-­Columbian collection in the 1910s. Natural history museums, and occasionally museums with comprehensive collections ranging from geological specimens to historical artifacts, were the primary places where one saw the material culture of the ancient Americas. These included the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the Field Columbian Museum (now the Field Museum) in Chicago, the US National Museum (now the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History) in Washington, DC, and the Brooklyn Museum. It is worth noting here that while art history was still a relatively young discipline in the United States in the early twentieth century, the fields of archaeology and anthropology were more developed, and some of the first works of Pre-Columbian art history were produced in the context of anthropology departments. Herbert Spinden, for example, completed his thesis in anthropology at Harvard University in 1909; it was later published as A Study of Maya Art: Its Subject Matter and Historical Development (1913).6 Spinden went on to a career in museums, first at the American Museum of Natural History, and then ultimately at the Brooklyn Museum, very astutely collecting both ancient and colonial Latin American art at time when its larger rival, the Met, was looking the other way. Rockefeller’s position that works from the Pre-­ Columbian Americas were fine art and deserved to be in the Met came about in the wake of artists’ interest in Pre-­Columbian sculpture. As interest in modern art grew, so did interest in some of its sources, and as a result, Pre-­ Columbian art began to be displayed with greater regularity in art museums in the United States and Europe. By 1927, the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University devoted one gallery to Maya art loaned by the Peabody Museum. In Paris, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs organized Arts anciens de l’Amérique at the Musée du Louvre in 1928. This exhibition of more than a thousand works from Alaska, 6. Herbert J. Spinden, A Study of Maya Art: Its Subject Matter and Historical Development, Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 6 (Cambridge, MA: The Museum, 1913). 124 latin ame r ican and latinx visual cultu r e Canada, Mexico, Central America, and South America included loans from the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro and other public museums in France; private collections throughout Europe; and the Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnografía in Mexico City. By the last quarter of the twentieth century, major art museums in the United States and many in Europe had more or less welcomed ancient American art into the fold on a permanent basis. But where to place Pre-Columbian art in an encyclopedic museum? The material culture of Latin America before the arrival of Europeans has fallen under multiple rubrics in the past century. Particularly in the middle of the twentieth century, it was grouped with African and Oceanic arts, first under the term “primitive” and later as the catchall of “others” outside of Asia as “the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.” But it has also been located within a broader hemispheric designation as “arts of the Americas,” both early in the twentieth century, as at the Santa Barbara Art Museum in California, and more recently in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts’ Art of the Americas wing. But do either of these really make sense? Both groupings have been criticized as colonialist—the former because those regions were once dominated by European imperial powers, the latter for its hemispheric and hegemonic associations—and reductive, as they skip over the historical circumstances of the groupings. Methodologically, if not entirely chronologically, Pre-­Columbian sits more comfortably with other ancient traditions. But does that isolate and distance this heritage from concerns of today? And on a purely practical level, does an “ancient” designation make our field even more vulnerable to directors (and deans) looking to reach younger audiences—­students and museum visitors who are increasingly interested only in the present? In Latin America, there has historically been a greater divide between Pre-Columbian and post-Columbian art, with the material culture of the Americas before the arrival of Europeans generally considered the domain of the social sciences. Although things are changing, in many universities, the art history of Latin America begins in the sixteenth century. Museums in Latin America have mirrored this division up to a point: Pre-Columbian objects were in museums of anthropology and archaeology, not fine arts museums. In Mexico City, the Museo Nacional, founded in 1825, held the historical, archaeological, and natural history collections. The natural history collections were moved out in 1913, and the archaeological and ethnographic collections were eventually moved to their own building, becoming the Museo Nacional de Antropología, which opened in 1964. This spectacular museum and its incomparable collections has remained the major institution where one can see the arts of ancient Mexico. Mexico City’s Museo Nacional de Arte, established in 1982, covers the visual arts from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-­twentieth century. Private museums in Latin America, however, have cut across disciplinary and chronological lines. Often smaller and nimbler, they are important centers for Pre-Columbian visual studies. The Museo de Arte de Lima, for example, founded in 1961, has become a major driver of art-historical research of the ancient Andes, interestingly in the absence of any major academic art history programs in that city. The Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, established in ­Santiago in 1981, has likewise been a major center for the study of the arts of the ancient Americas through its permanent installations, temporary exhibitions, and publications. In Mexico, a number of newer museums, such as the Museo Amparo in Puebla and the Museo Soumaya in Mexico City, include works from ancient to contemporary. The point I wish to make here is that internationally, museums are major drivers of research on the arts of the ancient Americas, and not just through temporary exhibitions, but also through a variety of online platforms. The Met, admittedly at the extreme end of the scale in terms of size, has impressive online offerings, from the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, which pairs essays and works of art with chronologies to tell the story of global art and culture, to the online catalogue, blogs, and other outputs. To put things in perspective, a large museum like the Met— often called “a college of curators”—has the same number of curators—120—as small liberal arts colleges have professors, but in the case of the Met, the scholars are all dedicated to art history. Combined with the fellowship program with its nearly sixty yearlong appointments, it is a lively research community at the forefront of object-based research and collaborative projects with scholars in allied fields such as conservation and materials science. And its reach is vast. While more than seven million people visit the Met in person each year, that tally is dwarfed by the number of individuals across the globe who access its collections, exhibitions, lectures, and other features virtually. To give only one example, the FacebookLive tour of the Golden Kingdoms exhibition at the Met garnered some 45,000 views that day, and another 62,000 when we repeated the tour in Spanish. In a world where art history textbooks are costly or unavailable, the Met’s website, and those of other museums and research institutes, with content freely available, including images for publication, have become increasingly important presences in the study of art history globally. This is no time to rest on our laurels, however. The study of the arts of the ancient Americas is under threat at both the museum and the university. Issues surrounding repatriation or “decolonizing” the museum receive the greatest attention in the press, but museums also face financial challenges. New philanthropy is drawn more to science and start-up types of charitable initiatives. The field of ancient American art, in particular, is especially challenged in the context of the museum: with the near collapse of the antiquities market in the United States since 2008, major donors formerly drawn to this field have largely disappeared. In that year, the board of directors of the American Alliance of Museums approved a measure recommending that museums require documentation that an object under consideration for acquisition was out of its probable country of modern discovery by November 17, 1970, the date on which the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property was signed. The impact of this was felt immediately in museums: a slowdown, if not a complete halt, in acquisitions. But it has also meant the loss of a traditional group of supporters who are in agreement with the ethics behind this decision and have ceased to collect or turned to other fields. As much as we don’t want to acknowledge a connection between the market and the academy, it is likely to affect the university world as well, if only by diminishing employment opportunities for graduates. Static collections and a dearth of supporters make curatorial positions vulnerable. Universities are increasingly shifting resources toward Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics departments. This applies to increases in numbers of new faculty positions as well as to the support of programs and departments more generally. The significant expansion in the size of faculties in colleges and universities around 1980 to which I alluded above has long since slowed to a trickle, or even reversed. This is particularly true for departments in the humanities. It is fair to say that there is virtually no department in the history of art at a liberal arts college today that can expect, or even hope, to add a position (that is, achieve a net addition in the size of its department faculty). Moreover, they have to fight to hold onto the positions they have that come open through retirements. There Dialogues 125 is no evidence that this is going to change. Despite multiple studies on the importance of the humanities in the pursuit of any career, university administrators, and also parents and students, are increasingly wary of humanities degrees. Several articles about this situation have appeared just in the past months in the Chronicle of Higher Education. Yet now more than ever, the skills traditionally associated with art history, such as the effective communication of visual and cultural analysis orally and in writing, are crucial in a world that is becoming more image and less text based. It is heartening to see medical schools recognizing the importance of visual analysis and working with art history departments and museums to develop clinical skills through strengthening the practice of observation to understand the ambiguities of images. Art historian Susan ­Sidlauskas of Rutgers University, for example, has developed an interdisciplinary course with colleagues from Rutgers’s Robert Wood Johnson Medical School to help medical students become more observant diagnosticians. Similar programs now exist at many other universities, including Harvard, Stanford, the University of Texas, and Yale. But art history is not simply a matter of learning to look. One of its great strengths has always been its openness to other disciplines and its embrace of approaches from allied fields to understand the complexities of image making and its reception. Bruno Latour’s classic 1998 essay “How to Be Iconophilic in Art, Science, and Religion,” for example, reminds us that art history’s great strength is not so much visual acuity as its ability to grapple with mediations of images.7 Art history, more than other disciplines, contends with the heterogeneity and instability of social contexts in which works of art are created and understood. Despite the many challenges we face in the field of Pre-­ Columbian visual studies, I remain optimistic. In the final days of the Golden Kingdoms exhibition, it was soul affirming to spend time in the packed galleries (Figure 1). Exhibitions are great drivers of research, from the initial studies that eventually lead to the preparation of a catalogue, to continued observations during the installation of the works, through discussions with visitors when the works are on view. Astute comments and questions from the public prompt further reflections, including on the very nature 7. Bruno Latour, “How to Be Iconophilic in Art, Science, and Religion,” in Picturing Science, Producing Art, ed. C. A. Jones and P. Galison, with A. Slaton (New York: Routledge, 1998), 418–40. 126 latin ame r ican and latinx visual cultu r e Exit of the exhibition Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, 2018, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo © Anna-Marie Kellen, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Figure 1. of the creation of histories. Golden Kingdoms was an acute reminder of ways in which we try to understand the past, and the sharp distinctions between what we know from historical texts and what we know from archaeology and the objects themselves. It has become a platitude to say that history is written by the victors, but the first official histories of the Pre-Columbian world were written decades after the glittering cities of the ancient Americas had been destroyed, their populations devastated. Many were composed to justify the conquest, to present the Indigenous populations of the ancient Americas as benighted and in desperate need of salvation. And these histories cast a surprisingly long shadow onto present-day understandings of the history of Latin America before the arrival of Europeans. Surely now, more than ever, a deeper and more nuanced understanding of this history is of profound importance. Visual studies are an antidote to text-based views of the past. What we know from art history and archaeology is distinct from what we know from historical sources. Thanks to the objects themselves, we know more about populations that are under-addressed in the written texts, such as women, and populations outside of major urban centers. But we also know about the striking achievements of some of the greatest artists of the Pre-Columbian Americas, who, just like their contemporaries in Europe, were working for the great patrons of their time. For the most part we lack their names (see Lisa Trever’s contribution to this conversation) and we understand frustratingly little of the contexts in which these works were produced.8 For traditionalists, the absence of such specificities is a hindrance. To others it is liberating, leading to innovative new approaches.9 Either way, it is important to bear in mind that in the context of global art history, the biographies of makers and their patrons comprise a comparatively small subset of potential areas for exploration in visual studies. One of the great appeals of the study of the arts of the ancient Americas is its potential for expanding the ways 8. See also Lisa Trever, The Archaeology of Mural Painting at Pañamarca, Peru, with contributions by Jorge Gamboa, Ricardo Toribio, and Ricardo Morales (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2017). 9. On the identity of artists and patrons see Stephen Houston, “Crafting Credit: Authorship among Classic Maya Painters and Sculptors,” in Making Value, Making Meaning: Techné in the Pre-Columbian World, ed. Cathy Costin (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2016), 391–431. On the absence of texts as a liberation, this was a point made by Svetlana Alpers in response to a paper I delivered at CASVA’s twenty-fifth anniversary celebration at the National Gallery of Art in 2005, later published as “Reading Art without Writing: Interpreting Chimú Architectural Sculpture,” in Dialogues in Art History, from Mesopotamian to Modern: Readings for a New Century, ed. Elizabeth Cropper, Studies in the History of Art 74, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Symposium Papers LI (­Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2009), 72–89. On the issue of the identity of artists in other-than-Western art see Alisa LaGamma, ed., African Arts 31, no. 4 (1998); Alisa LaGamma, ed., African Arts 32, no. 1 (1999). in which we think of the visual arts in general—materials and their associated meanings, the processes of creation, the place of objects in the lives of individuals and communities, and a multitude of other subjects that we are just beginning to explore in this comparatively young field. In closing, I feel compelled to emphasize as strongly as possible that the art history of the Pre-Columbian Americas is crucial, not just as prelude to the present, but also as a reminder of how, at any time and any place, ideas are given visual form, and how these works speak to the heart of who we are as human beings. Joanne Pillsbury Metropolitan Museum of Art A B O U T T H E AU T H O R Joanne Pillsbury—is Andrall E. Pearson Curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Her edited volumes include Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies, 1530–1900 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), Past Presented: Archaeological Illustration and the Ancient Americas (Harvard University Press, 2012), and Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas (Getty Publications, 2017). Dialogues 127