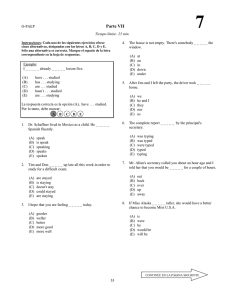

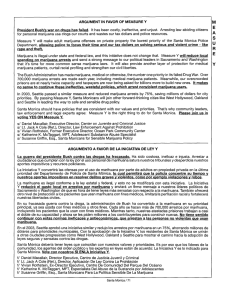

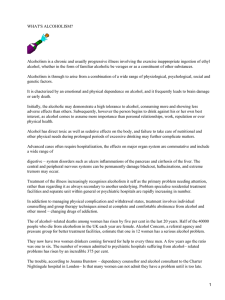

Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67 (2002) 301 /309 www.elsevier.com/locate/drugalcdep Effects of oral THC maintenance on smoked marijuana selfadministration Carl L. Hart *, Margaret Haney, Amie S. Ward, Marian W. Fischman, Richard W. Foltin Division on Substance Abuse, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Dr., Unit 120, New York, NY 10032, USA Received 29 October 2001; received in revised form 16 April 2002; accepted 18 April 2002 Abstract Studies have shown that the D9-tetrahydrocannabinol (D9-THC) concentration in marijuana cigarettes is an important factor for the maintenance of marijuana self-administration. Yet, the impact of oral D9-THC treatment on marijuana self-administration is unknown. Because other agonist therapies have been demonstrated to be effective for the treatment of substance use disorders, the objective of this study was to evaluate the influence of oral D9-THC maintenance on choice to self-administer smoked marijuana. During this 18-day residential study, 12 healthy research volunteers received one of three doses of oral D9-THC capsules (0, 10, 20 mg QID) for 3 consecutive days, followed by 3 consecutive days of matching placebo. The order of active D9-THC administration was counterbalanced. Each morning, except on days 6, 12, and 18, participants smoked the ‘sample’ marijuana cigarette (1.8% D9THC w/w) and received a $2 voucher (redeemable for cash at study’s end). Following the sample, volunteers participated in a fourtrial choice procedure during which they had the opportunity to self-administer either the dose of marijuana they sampled that morning or to receive the $2 voucher. Relative to placebo D9-THC maintenance, participants’ choice to self-administer marijuana was not significantly altered by either of the two active D9-THC maintenance conditions. Some ‘positive’ subjective drug-effect ratings following the sample marijuana cigarette were reduced: by day 3 of active oral D9-THC maintenance, participants’ rating of ‘Good Drug Effect’ and ‘High’ were significantly decreased. Smoked marijuana-related total daily caloric intake was not significantly altered under any maintenance conditions. Finally, the effects of smoked marijuana on psychomotor task performance were only minimally affected by oral D9-THC maintenance. These data indicate that participants’ choice to self-administer marijuana was unaltered by the oral D9-THC dosing regimen used in the present investigation. # 2002 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Marijuana; Subjective effects; Choice; Self-administration; Food intake; Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol 1. Introduction Marijuana remains the most widely used illicit drug in the United States; D9-tetrahydrocannabinol (D9-THC), a psychopharmacologically active constituent of marijuana smoke, is thought to be essential for the maintenance of chronic marijuana smoking behavior. For example, oral D9-THC has been shown to serve as a positive reinforcer in humans under experimental conditions (Chait and Zacny, 1992). In addition, several * Corresponding author. Tel.: /1-212-543-5884; fax: /1-212-5435991 E-mail address: [email protected] (C.L. Hart). studies have provided experimental data supporting D9THC’s integral role in the reinforcing effects of smoked marijuana (Mendelson and Mello, 1984; Chait and Burke, 1994; Kelly et al., 1994, 1997). In these studies, participants ‘sampled’ two marijuana cigarettes, each containing different D9-THC concentrations, and subsequently were given an option to choose between the cigarettes. Marijuana cigarettes containing a higher concentration of D9-THC were consistently preferred to those containing a lower D9-THC concentration. Moreover, data from this laboratory have demonstrated that even when the choice between marijuana cigarettes varying in D9-THC content is not mutually exclusive, participants chose higher concentration D9-THC con- 03765-8716/02/$ - see front matter # 2002 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 3 7 6 - 8 7 1 6 ( 0 2 ) 0 0 0 8 4 - 4 302 C.L. Hart et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67 (2002) 301 /309 centration cigarettes more often than those containing lower D9-THC concentrations (Haney et al., 1997; Ward et al., 1997). Volunteers in those studies were presented with a choice between one marijuana cigarette and an alternative reinforcer (e.g. snack food, money). Three different D9-THC concentration cigarettes were compared to the alternative reinforcers repeatedly. While choice to self-administer marijuana was sensitive to alternative reinforcers, volunteers overwhelmingly selected more cigarettes containing higher D9-THC content than placebo and low D9-THC cigarettes. Together, these data bolster the hypothesis that marijuana selfadministration is related to D9-THC content. Previous laboratory research has shown that tobacco cigarette and heroin self-administration can be significantly decreased when research participants are maintained on agonist treatments (Mello and Mendelson, 1980; Benowitz et al., 1998; Comer et al., 2001). Employing non-treatment seeking daily cigarette smokers, Benowitz et al. (1998) reported that 63 mg of transdermal nicotine (the major psychoactive constituent of tobacco smoke) reduced the daily number of cigarettes smoked by nearly 30% and decreased the amount of nicotine obtained from each cigarette by 36% in comparison to a placebo patch. Similarly, in a recent laboratory investigation of buprenorphine’s (a partial m opioid agonist) ability to impact heroin self-administration by humans, Comer et al. (2001) found that progressive ratio (PR) break point values for heroin and ratings of subjective heroin effects were markedly lowered (/40 and 60%, respectively), during 16 mg buprenorphine maintenance compared to 8 mg. Additionally, although the effects of methadone maintenance on human heroin self-administration has yet to be assessed under laboratory conditions, the ability of methadone maintenance to substantially decrease illicit heroin use in a clinical setting has been well-documented (for review, see Kreek, 2000). These findings argue that agonist medications can be effective tools for decreasing drug-taking behavior. Given these considerations, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of oral D9-THC maintenance to modify choice to self-administer smoked marijuana by humans under controlled laboratory conditions. Using a double-blind, within-participant design, experienced marijuana smokers were maintained on oral D9-THC (0, 10, 20 mg QID) for 3 consecutive days. Choice to self-administer a marijuana cigarette (1.8% D9-THC w/w) or receive a $2 voucher (redeemable for cash at study’s end) was compared during different D9-THC maintenance conditions. Our hypothesis was that marijuana-related reinforcing and subjective effects would be significantly attenuated during active oral D9THC maintenance, relative to placebo. Because the number of individuals seeking treatment for marijuana dependence has increased in the past decade (SAMHSA, 1998) and because marijuana withdrawal (a syndrome that, in theory, should be mitigated by oral D9-THC administration) may be one factor maintaining continued marijuana use, the findings from the current investigation could have important clinical implications. 2. Methods 2.1. Participants Twelve healthy research volunteers, ranging in age from 21 to 45 years (mean/31.7), completed this 18day residential study. Of these participants, two were female (Black-American, White-American) and 10 were male (eight Black-American, two Hispanic-American). They were solicited via word-of-mouth referral and newspaper advertisement in New York City. All reported smoking marijuana every day, averaging 12 ‘joints’ per day (ranging between 1 and 35 joints per day). An important caveat for self-reported marijuana use history is that it is difficult to absolutely quantify the number of marijuana joints research participants smoked per day because many individuals in the New York City area report smoking ‘blunts.’ A blunt is comprised of approximately four joints rolled in tobacco cigar wrapping paper. In addition, most of the current research participants reported smoking with other individuals regularly. As a result, the likelihood of some participants underestimating or overestimating their daily marijuana consumption is fairly high. Seven participants reported current caffeine use (ranging between 2 and 5 cups per week), eight reported current alcohol use (ranging between 1 and 10 drinks per week) and seven reported current tobacco cigarette use (ranging between 2 and 20 cigarettes per day). Several urine toxicology screens during the screening process confirmed the absence of other illicit drug use, as D9-THC was the only drug metabolite present. During screening, all volunteers passed comprehensive medical and psychological evaluations, and were within normal weight ranges according to the 1983 Metropolitan Life Insurance Company height/weight table. Female volunteers were given a serum pregnancy test during the screening process, and subsequent random urine pregnancy tests throughout the experimental protocol. Participants were informed that they would have the opportunity to smoke one marijuana cigarette on five occasions daily for 15 days, and each 5-day period of marijuana availability would be separated by a day during which no marijuana would be available. They were also informed that they would be administered four capsules containing a FDA-approved medication at different times each day. Participants were told that the D9-THC concentration in the marijuana cigarettes and doses contained in the capsules could change at anytime C.L. Hart et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67 (2002) 301 /309 during the study. All volunteers were told that the purpose of the study was to evaluate the interactions of smoked marijuana and medications on ongoing behavior in a relatively naturalistic setting. Each participant signed a consent form approved by the New York State Psychiatric Institute’s Institutional Review Board. The consent form described the study and detailed any possible risks. At study completion and prior to discharge, participants were fully informed about experimental and drug conditions. For completing the entire study, research participants were compensated at a rate of $70 per day, which was paid in 2 weekly installments. 2.2. Laboratory Three groups of participants (each group consisting of four individuals) resided in a residential laboratory designed for the continuous observation of behavior over extended time periods (Foltin et al., 1996). Located within the New York State Psychiatric Institute, the facility consists of 11 rooms. The common social area, where participants were free to engage in recreation activities, is a large room that contains two couches, chairs, two video game machines, two television monitors for viewing videotaped films, free-weight exercise equipment, art supplies, reading materials, board games, and two washers/dryers. Participants were individually housed in four private bedrooms, each of which is furnished with a bed, desk, Macintosh LC computer system, microwave, toaster, refrigerator, food preparation space, and bar-code scanner (Worthington Data Solutions, Santa Cruz, CA). The bar-code scanner was used for food reporting and requesting. From 08:15 to 24:00, food (including caffeinated beverages) was available ad libitum, except during the work sessions when meals that required extended food preparation time were not allowed. Additionally, during this time period, participants had free monitored access to tobacco cigarettes. Immediately outside of bedrooms were two single-occupancy bathrooms and two single-occupancy showers. In addition, two vestibules located adjacent to the common social area were used for supervised medication administration and for daily exchange of all personal items and food. For the purpose of continuous observation of behavior, cameras and microphones were located throughout the common social area and in bedrooms. However, no microphones or cameras were located in bathrooms, showers or private dressing areas. Communication between the staff and participants was kept to a minimum and was primarily accomplished via a continuous on-line computer network system consisting of the computers in each participant’s bedroom and the control room computer. 303 2.3. Procedure Prior to residing in the laboratory, participants completed two 3/4 h training sessions in order to familiarize them with the computerized psychomotor tasks, subjective-effects visual analog questionnaire, and other study procedures. On 2 different days participants were administered a ‘sample’ of the substances used in the study: on the first day they smoked a marijuana cigarette (1.8% D9-THC concentration) and the second day they were given an oral D9-THC capsule (20 mg). The purpose of administering marijuana and oral D9THC before the study began was to provide volunteers with experience with the study marijuana and oral D9THC prior to study onset and to monitor any potential unusual reaction to them. Volunteers moved into the laboratory the day before the study began, received further training on the computerized psychomotor tasks, and were acclimated to experimental conditions. Each study day, participants were awakened at 08:15 and were instructed to submit urine samples, which were randomly tested for drug metabolites (amphetamines, cocaine, D9-THC, and morphine derivatives): D9-THC was the only drug metabolite present. Participants completed a visual analog sleep questionnaire, which consisted of 7 100-mm lines anchored with ‘not at all’ at the left end and ‘extremely’ at the right end, labeled with: ‘I slept well last night,’ ‘I woke up early this morning,’ ‘I fell asleep easily last night,’ ‘I feel clearheaded this morning,’ ‘I woke up often last night,’ ‘I am satisfied with my sleep last night,’ and a fill-in question estimating how many hours participants thought they slept the previous night (Haney et al., 2001). Additionally, they completed a 50-item subjective-effects visual analog questionnaire, which was a series of lines, each 100 mm long and labeled ‘not at all’ at one end and ‘extremely’ at the other end, presented one at a time (Haney et al., 1999b; Hart et al., 2001a). These lines are labeled with adjectives describing a mood (e.g. I feel. . . ‘Anxious,’ ‘Angry,’ ‘Frustrated’), a drug effect (e.g. I feel. . . ‘High,’ ‘Good Drug Effect,’ ‘Bad Drug Effect’), or a physical symptom (e.g. I feel. . . ‘Headache,’ ‘Stomach Upset,’ ‘Muscle Pain’). Participants were also weighed after voiding, but were not informed of their weight. Eight 30-min computerized task batteries, composed of a subjective-effects questionnaire, a drug-effect questionnaire, and psychomotor tasks were completed each day. Participants were given a 15-min break between each task battery. From 09:15 to 11:15, participants completed three task batteries, followed by a lunch period in which they had access to activities available in the social/recreational area until 12:30. The final five task batteries were completed from 13:00 to 17:00. On the drug-effect questionnaire, participants were required to rate ‘Good Effects’ and ‘Bad Effects’ from C.L. Hart et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67 (2002) 301 /309 304 secutive days of placebo D9-THC administration was included in order to examine residual D9-THC effects and as a washout period. The dose of oral D9-THC during the first 3 days of each block of sessions was counterbalanced. The oral D9-THC dosing order for the first four participants (1 /4) was 0, 10, and 20 mg (QID: total daily dose of 40 or 80 mg); participants 5/8 received 0, 20, and 10 mg (QID); and participants 9/12 received 10, 0, and 20 mg (QID). Because the recommended clinical dose of oral D9-THC (2.5 /5 mg BID: total daily dose of 5 /20 mg) is well below doses used in this study, as a safety precaution, the 20 mg dose was never administer during the first block of sessions. Each 5-day period of marijuana availability was followed by 1 day during which no marijuana was available. the drug on a five-point scale: 0/‘not at all’ and 4 / ‘very much.’ They were also asked to rate how ‘Strong’ the drug-effect was as well as their desire ‘to take the drug again.’ Lastly, participants were ask to rate how much they liked the drug effect on a nine-point scale: / 4 indicated ‘disliked very much,’ 0 indicated ‘feel neutral, or feel no drug-effect,’ and 4 indicated ‘liked very much.’ The drug-effect questionnaire was administered 45 min after each marijuana dosing occasion and participants were instructed to rate their responses based on the marijuana cigarette most recently, smoked. Only the drug-effect questionnaire completed after the sample marijuana dose was included in the data analysis. Psychomotor tasks (Haney et al., 1999b) consisted of a 3-min Digit-Symbol Substitution Task (McLeod et al., 1982), a 3-min repeated-acquisition task (Kelly et al., 1993), a 10-min divided attention task (Miller et al., 1988), a 10-min rapid information task (Wesnes and Warburton, 1983), an immediate and delayed digitrecall task, followed by a 15-min rest period. Beginning at 17:00 h, participants had access to activities available in the social/recreational area. Two videotaped films were shown nightly, beginning at 18:15 and 21:30. Lights were turned out at 24:00. 2.5. Food monitoring A food box, which contained various meal items, conventional snacks, and beverages, was distributed to each participant daily at 08:30. Food boxes did not contain frozen food items; these items were kept in a freezer in an adjacent room and were available via request. To facilitate choice of frozen meals, participants were provided with a book containing package pictures of each item. Between 08:15 and 24:00, participants were free to request additional units of any items as desired and could consume food items ad libitum. Water could be consumed at any time. Participants were informed that their food intake was monitored continuously, and were instructed to scan custom-designed bar codes whenever they ate or drank, specifying substance and portion. Research monitors in the adjacent control room acknowledged the report and also kept a handwritten record of food consumption. Participants could cancel a food report, or change portion size, using the customized bar codes. Wrappers for each item were color-coded by participant to facilitate data collection. Trash was removed and examined daily to validate verbal reports and observer records of food intake, and to control for the possibility of food hoarding. 2.4. Experimental design A representative study design is shown in Table 1. This study consisted of three 6-day blocks of sessions. At 09:45 during the first 5 days of each block (days 1/5, 7 /11, and 13 /17), participants sampled the reinforcers available that day: they smoked one marijuana cigarette (1.8% D9-THC cigarettes were the only cigarettes available throughout the study) and were given a $2 money voucher, which was redeemable for cash at the end of the study. For the remaining marijuana-dosing times (12:35, 16:00, 19:00, 22:00), participants were given the option to smoke the sampled marijuana cigarette or to receive the $2 money voucher. Additionally, one of three doses of oral D9-THC capsules (0, 10, 20 mg QID; 09:00, 12:30, 17:00, 21:00) were administered during the first 3 days of each block of sessions, followed by 3 consecutive days of placebo D9-THC administration. The 3 con- Table 1 Representative study design for assessing the effects of oral D9-THC on smoked marijuana (MJ) Block number 1 2 3 Day 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Oral D9-THCa MJ choiceb 0 Y 0 Y 0 Y 0 Y 0 Y 0 N 10 Y 10 Y 10 Y 0 Y 0 Y 0 N 20 Y 20 Y 20 Y 0 Y 0 Y 0 N First marijuana dose on each choice day was a sample. During all other opportunities, participants were presented with a choice between one marijuana cigarette (1.8% D9-THC) and a $2 voucher. Y Choice day. N No choice day. a Oral THC dosing times (09:00, 12:30, 17:00, 21:00). b Choice/marijuana times (09:45, 12:35, 16:00, 19:00, 22:00). C.L. Hart et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67 (2002) 301 /309 2.6. Drug During sample dosing and when smoked marijuana was the selected option, participants smoked a single 1-g marijuana cigarette (1.8% D9-THC w/w, provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse), while under video observation, using a paced-puffing procedure previously shown to produce concentration-dependent changes in heart rate and subjective-effects ratings (Hart et al., 2001b). They were instructed to take three puffs from the marijuana cigarette: each puff consisted of a 5-s preparation interval, followed by 5 s of inhalation, 10 s of breath-hold, and 40 s of exhalation and rest. Cigarettes were tightly rolled at both ends and were smoked through a hollow plastic cigarette holder so that the contents were not visible. At least 12 h prior to administration, cigarettes were removed from a freezer, where they were stored in an airtight container, and humidified at room temperature. Small tablets of oral D9-THC (Unimed Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) were repackaged by the Pharmacy Department of the New York State Psychiatric Institute by placing D9-THC into red #00 opaque capsules and adding lactose filler. Placebo D9-THC contained only the filler. 2.7. Data analysis Data for smoked marijuana choices and the drugeffect questionnaire were analyzed using two-factor repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA): the first factor was oral D9-THC maintenance condition (0, 10, 20 mg) and the second factor was day of maintenance condition (1 /5). When the ANOVA revealed a significant dose by day interaction, post hoc analyses were performed to answer the following question: (1) do the effects produced by oral D9-THC maintenance differ from the effects produced by placebo maintenance? To evaluate potential differences between effects produced by the oral D9-THC maintenance conditions, each day of each oral D9-THC maintenance condition was compared to the corresponding day of each other oral D9-THC maintenance condition (e.g. placebo oral D9THC, day 1 versus 10 mg oral D9-THC, day 1). Data from day 6 were not included in the analysis because marijuana cigarettes were not available on this day. Data for the subjective-effects visual analog questionnaire and psychomotor performance were analyzed using three-factor repeated measures ANOVAs: the first factor was oral D9-THC maintenance condition (0, 10, 20 mg), the second factor was day of maintenance condition (1 /5), and the third factor was time after the sample marijuana cigarette (15 and 45 min post the sample marijuana dose). Analyses were performed only on subjective ratings and psychomotor performance data collected after the sample marijuana cigarette for each oral D9-THC condition because each participant 305 chose to self-administer varying numbers of marijuana cigarettes during each maintenance condition. Change from baseline scores for the two subjective-effects questionnaires and performance scores obtained after administration of the sample marijuana cigarette were compared among the various drug conditions. Change from baseline scores were used because there are subtle day-to-day differences on some dependent measures and participants’ task performance often gradually improves over the course of a study. Data from the subjectiveeffects questionnaire and psychomotor battery that were completed from 09:15 to 09:45 provided baseline scores for each day. As stated above, post hoc tests were performed to evaluate potential differences between effects produced by the oral D9-THC maintenance conditions, each day of each oral D9-THC maintenance condition was compared to the corresponding day of each other oral D9-THC maintenance condition. Total caloric intake, gram intake of carbohydrate, fat, and protein, proportion of caloric intake from each macronutrient (estimated as kcal from g-intake using Atwater factors (McLaren, 1976)), mean number of eating occasions, and eating occasion size were measured. Mean number of eating occasions and eating occasion size were determined using a minimal interoccasion interval of 10 min: an eating occasion was defined as beginning with the first report of consuming an item and ending when there was a pause of greater than 10 min between food reports. As described above for smoked marijuana choices, food intake data were analyzed using two-factor repeated measures ANOVA: the first factor was oral D9-THC maintenance condition (0, 10, 20 mg) and the second factor was day of maintenance condition (1 /5). The same post hoc analyses were performed. Only those P values B/0.05 were considered statistically significant and HunyhFeldt corrections were used, when appropriate. 3. Results 3.1. Reinforcing effects Table 2 displays the number of marijuana cigarettes chosen as a function of the oral D9-THC maintenance dose. Relative to placebo D9-THC maintenance, participants’ choice to self-administer marijuana was not significantly altered by either of the two active D9-THC maintenance conditions as indicated by the lack of a dose by day interaction (F (8, 88) /1.67, P / 0.12). 3.2. Subjective effects Fig. 1 shows ratings of ‘Good Drug Effect’ (left panel) and ‘High’ (right panel) following the sample marijuana cigarette (1.8% D9-THC) as a function of oral D9-THC C.L. Hart et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67 (2002) 301 /309 306 Table 2 Total number of marijuana options selected under each oral D9-THC condition and self-reported drug use by each participant Selected MJ options under oral D9-THC conditions Self-reported drug use Participant Sex Age Daily MJ cigarettesa Daily tobacco cigarettes Weekly alcoholic drinks 0 mg 10 mg 20 mg 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 12 12 12 12 12 12 8 12 2 4 6 0 7 12 11 12 11 12 9 12 7 12 10 1 M M M M M M F M M M M F 21 39 37 33 43 25 27 22 26 38 24 45 3.5 15 25 10 1 10 2 2 25 35 22 3 6 10 0 6 0 2 10 3 0 20 0 0 0 1 0 5 2 2 0 10 0 10 6 2 10 12 12 12 9 10 10 12 7 12 9 11 Maximum number of doses available per participant under each oral D9-THC condition was 12 (four choices across 3 days of active oral D9-THC maintenance). MJ marijuana. a One ‘blunt’ was classified as four ‘joints’ cigarettes. maintenance dose and day. Analysis of ‘Good Drug Effect’ data revealed a significant dose by day interaction (F (8, 88) /2.67, P B/ 0.03). On days 1 and 3, volunteers reported significantly reduced ratings of ‘Good Drug Effect’ following the sample marijuana cigarette while being maintained on 20 mg oral D9-THC compared to placebo D9-THC maintenance (P B/ 0.05 and P B/ 0.0001, respectively); on day 3 of 10 mg oral D9THC maintenance, ratings of ‘Good Drug Effect’ were significantly reduced, relative to placebo maintenance (P B/ 0.0001). Day 1 was the only day that the active maintenance conditions differed from each other: ratings were significantly decreased under the high-dose condition, relative to low-dose condition (P B/ 0.01). During the period after active oral D9-THC maintenance (day 4 only), ratings of ‘Good Drug Effects,’ under both active D9-THC conditions, remained markedly lower than those under the placebo oral D9-THC condition (P B/ 0.01). Analysis of ‘High’ data also revealed a significant dose by day interaction (F (8, 88) /4.37, P B/ 0.001). On day 1, participants reported significantly greater ratings of ‘High’ following the sample marijuana cigarette while being maintained on 10 mg oral D9-THC, relative to placebo and 20 mg D9-THC maintenance (P B/ 0.0001). On day 3 of placebo oral D9-THC maintenance, ratings of ‘High’ were significantly increased, relative to both active maintenance conditions (PB/ 0.03). During the period following active oral D9-THC maintenance (days 4 and 5), ratings of ‘High,’ under 20 mg D9-THC Fig. 1. Selected mean subjective-effects ratings following the sample marijuana cigarette (1.8% D9-THC) as a function of oral D9-THC maintenance dose and day. Data are represented as change from baseline scores. Error bars represent one S.E.M. Overlapping error bars were omitted for clarity. C.L. Hart et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67 (2002) 301 /309 maintenance, remained significantly lower than those under the placebo oral D9-THC condition (P B/ 0.01). No other significant effects were observed for subjectiveeffects visual analog data and no significant effects were noted for drug-effect questionnaire data. 3.3. Performance effects There were few performance alterations observed during D9-THC maintenance. The only significant dose by day interaction was observed during the immediate digit-recall task (F (8, 88) /3.05, P B/ 0.02). On day 2, volunteers correctly recalled more digits under the 20 mg condition compared to the 10 mg condition (P B/ 0.001). On day 4, the period following active oral D9-THC maintenance, participants correctly recalled fewer digits under the 20 mg condition, relative to the placebo and 10 mg condition (P B/ 0.03 and P B/ 0.02, respectively). 3.4. Food intake Analysis of mean caloric intake during each meal revealed a significant dose by day interaction (F (8, 88) /4.67, P B/ 0.001). On day 1, participants’ mean caloric intake during each meal was significantly increased during both active maintenance conditions compared to placebo maintenance (P B/ 0.01), whereas on day 3, mean caloric intake during each meal was significantly reduced during both active maintenance conditions, relative to placebo maintenance (P B/ 0.05). Nevertheless, no significant marijuana-related effects on daily total caloric intake were observed. The mean daily total caloric intake for each condition was as follows: 2848 kcal (placebo D9-THC maintenance), 2606 kcal (10 mg D9-THC maintenance), and 2669 kcal (20 mg D9THC maintenance). Additionally, the mean daily total caloric intake for the 3 days that marijuana was not available (days 6, 12, and 18) was 2902 kcal. A significant dose by day interaction was observed when the mean number of daily eating occasions was analyzed (F (8, 88) /2.55, PB/ 0.05). Relative to placebo maintenance, on days 1 and 2 the mean number of eating occasions was significantly decreased by 10 mg D9-THC maintenance (P B/ 0.03) and on day 2 by 20 mg maintenance (P B/ 0.001). 3.5. Sleep questionnaire Active THC maintenance exerted no significant effect on how participants’ rated the previous night’s sleep. 4. Discussion Findings from this study show that choice to selfadminister marijuana was not altered during active oral 307 D9-THC maintenance. Only a few positive subjectiveeffects ratings obtained after smoking the sample dose were reduced under both active D9-THC conditions. Psychomotor performance after smoked marijuana was not markedly impaired during active D9-THC maintenance. Consistent with performance, oral D9-THC maintenance did not substantially alter the effects of smoked marijuana on participants’ food intake and rating of the previous night’s sleep. Smoked marijuana preference was not significantly altered when volunteers were maintained on oral D9THC. These results were unexpected because of the substantial body of research indicating a pivotal role for D9-THC in marijuana’s reinforcing effects and because of previously reported data demonstrating that nicotineand heroin-associated reinforcing effects are substantially influenced by agonist treatment (Mello and Mendelson, 1980; Benowitz et al., 1998; Comer et al., 2001). There are several possible explanations as to why oral D9-THC did not have a greater effect on marijuana self-administration in the current study. First, the D9THC maintenance regimen employed consisted of only 3 consecutive days of active treatment, which may have been an insufficient time frame to produce substantial reductions in marijuana-related reinforcing effects. Because the volunteers tested in this study reported daily marijuana use (averaging 12 joints per day) and because D9-THC directly reinforces marijuana smoking with each inhalation, the behavior of smoking marijuana had become well-learned, not only owing to D9-THC’s primary reinforcement, but also because of conditioned reinforcers associated with the act of smoking marijuana. That is, smoking-related stimuli repeatedly paired with marijuana self-administration may elicit responses similar to those produced by marijuana, making marijuana-taking behavior difficult to extinguish, even though the amount of D9-THC (the probable primary reinforcer) obtained from smoking might be less reinforcing. Evaluating the reinforcing efficacy of nicotine and de-nicotinized cigarettes in non-treatment seeking cigarette smokers, Shahan and colleagues reported data consistent with this hypothesis (Shahan et al., 1999). They showed that the two different types of cigarettes produced similar reinforcing effects when cigarette choice was not mutually exclusive, suggesting that factors other than nicotine were maintaining cigarette smoking reinforcement. Others have also demonstrated the reinforcing efficacy of drug-related conditioned stimuli in laboratory animals (Schuster and Woods, 1968; Davis and Smith, 1976; Smith et al., 1977). A second possible reason that a greater decrease in marijuana-related reinforcing effects was not observed during oral D9-THC maintenance is because the selfadministration procedure employed in the current study was not sufficiently sensitive. Many investigators have 308 C.L. Hart et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67 (2002) 301 /309 used PR schedules (for review, see Richardson and Roberts, 1996; Haney et al., 1998), during which response requirements are systematically increased until the participant’s performance diminishes below some criterion level. As a result, the maximum amount of work a participant is willing to perform in order to support drug-taking behavior can be estimated. Perhaps a PR schedule would have revealed a clearer doserelated effect and shown a greater impact of oral D9THC maintenance on smoked marijuana self-administration. A third possible reason the reinforcing effects of smoked marijuana were not decreased more by oral D9-THC maintenance is that the D9-THC doses tested were too large (oral D9-THC doses used in the current study were 8/16 times greater than the recommended clinical doses). Administration of oral D9-THC produces several behavioral effects, including increased positive subjective ratings and self-administration (Mendelson and Mello, 1984; Haney et al., 1999a). In light of this knowledge, it is conceivable that participants interpreted oral D9-THC-associated effects as those produced by smoked marijuana, thus decreasing the likelihood of observing alterations of smoked marijuana-related reinforcing effects. Positive subjective-effects data obtained after the sample marijuana cigarette, however, argue against this supposition as the only cause because, under both active oral D9-THC maintenance conditions, ratings of ‘Good Drug Effect,’ and ‘High,’ were significantly decreased following smoking of the sample marijuana cigarette, indicating that volunteers experienced smoked marijuana’s subjective effects differently during active oral D9-THC maintenance. This finding is congruent with a previous investigation, which demonstrated diminished smoked marijuana-associated positive subjective effects during oral D9-THC maintenance (Jones et al., 1981). Moreover, the dissociation of drugrelated reinforcing and subjective effects has been well documented by several investigators using different classes of drugs (e.g. Johanson and Uhlenhuth, 1980; Fischman et al., 1990; Comer et al., 1997). It may be that in order to markedly decrease marijuana’s reinforcing effects, pharmacological interventions would have to decrease marijuana-induced subjective effects substantially more than those decreases observed in the current study. Another possible reason choice to smoke marijuana was not markedly decreased under active oral D9-THC maintenance is because participants altered their smoking behavior such that they titrated their amounts of smoked D9-THC exposure while continuing to choose it. Indeed, the administration of controlled concentrations of self-inhaled substances to humans is difficult due to variability in inhalation volume, lung capacity, depth of hold, etc. However, the current study employed a pacedpuffing procedure, which is designed to decrease the variability in inhalation parameters. These procedures have regularly produced D9-THC concentration-dependent changes in mood and cardiovascular activity following marijuana smoking. For example, in a recent study, the smoking procedure employed in the current study produced dose-related heart rate and subjectiveeffects ratings increases, (Hart et al., 2001b). Thus, the likelihood of changes in participants’ marijuana smoking behavior substantially influencing choice selections appears to be minimal. One major caveat of the current study’s design is that participants in the same group received an identical D9THC maintenance condition order (i.e. oral D9-THC conditions were not counterbalanced within each group). This factor potentially functioned as a social contagion. For example, on average, the third group of participants studied (participants #9 /12) selected considerably fewer smoked marijuana options than the other two groups. It is possible that participants’ choice behavior was influenced by choice selections of their fellow participants. In an effort to minimize such an effect, each participant was required to indicate their choices in the privacy of their room on a personal computer that was linked to the control room computer without knowledge of other study participants’ choice. Nevertheless, future studies should counterbalance within groups of participants to avoid this potential social confounder. The observation that the study drugs did not substantially impair psychomotor performance was not unexpected given that volunteers tested in this study were daily marijuana users. There is a growing body of literature supporting the hypothesis that regular marijuana users have learned (presumably through repeated practice) to be more cautious when executing challenging activities (e.g. cognitive operations) during intoxication (Ward et al., 1997; Haney et al., 1999b; Hart et al., 2001b), thereby decreasing the likelihood of observing D9-THC-related cognitive and psychomotor performance impairments in this population. Finally, the oral D9-THC maintenance doses examined in the current study did not markedly alter marijuana-related food intake effects. In conclusion, although D9-THC is thought to be integrally involved in smoked marijuana-related reinforcing effects, the majority of participants’ choice to selfadminister marijuana was unaltered by the oral D9-THC dosing regimen used in the present investigation. These data suggest that other factors (e.g. conditioned reinforcers) may also be critically involved in the maintenance of smoked marijuana-taking behavior and they underscore the need for further study of mechanisms involved in marijuana reinforcement. Future studies should increase the length of the oral D9-THC maintenance period in an effort to extinguish the effects of C.L. Hart et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67 (2002) 301 /309 marijuana-related conditioned stimuli, and employ other self-administration procedures. Acknowledgements This research is dedicated to the memory of our mentor Dr Marian Fischman, who died before publication of this manuscript. We thank the National Institute on Drug Abuse for financial support (DA-09236). The assistance of Shannon Lewis, Rachelle Reis-Larson, Christine Figueroa, Nicole Cain, Mabel Torres, Tom Melore, and Drs Cindy M. Pudiak, Evaristo Akerele and Jeffrey Wilson are gratefully acknowledged. References Benowitz, N.L., Zevin, S., Jacob, P. 1998. Suppression of nicotine intake during ad libitum cigarette smoking by high-dose transdermal nicotine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 287, 958 /962. Chait, L.D., Burke, K.A. 1994. Preference for high- versus lowpotency marijuana. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 49, 643 /647. Chait, L.D., Zacny, J.P. 1992. Reinforcing and subjective effects of oral D9-THC and smoked marijuana in humans. Psychopharmacology 107, 255 /262. Comer, S.D., Collins, E.D., Fischman, M.W. 1997. Choice between money and intranasal heroin in morphine-maintained humans. Behav. Pharmacol. 6, 677 /690. Comer, S.D., Collins, E.D., Fischman, M.W. 2001. Buprenorphine sublingual tablets: effects of IV heroin self-administration by humans. Psychopharmacology 154, 28 /37. Davis, W.M., Smith, S.G. 1976. Role of conditioned reinforcers in the initiation, maintenance and extinction of drug-seeking behavior. Pavlov. J. Biol. Sci. 11, 222 /236. Fischman, M.W., Foltin, R.W., Nestadt, G., Pearlson, G.D. 1990. Effects of desipramine maintenance on cocaine self-administration by humans. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 253, 760 /770. Foltin, R.W., Haney, M., Comer, S.D., Fischman, M.W. 1996. Effects of fluoxetine on food intake of humans living in a residential laboratory. Appetite 27, 165 /181. Haney, M., Collins, E.D., Ward, A.S., Foltin, R.W., Fischman, M.W. 1998. Effects of pergolide on intravenous cocaine self-administration in men and women. Psychopharmacology 137, 15 /24. Haney, M., Comer, S.D., Ward, A.S., Foltin, R.W., Fischman, M.W. 1997. Factors influencing marijuana self-administration by humans. Behav. Pharmacol. 8, 101 /112. Haney, M., Ward, A.S., Comer, S.D., Foltin, R.W., Fischman, M.W. 1999a. Abstinence symptoms following oral THC to humans. Psychopharmacology 141, 385 /394. Haney, M., Ward, A.S., Comer, S.D., Foltin, R.W., Fischman, M.W. 1999b. Abstinence symptoms following smoked marijuana in humans. Psychopharmacology 141, 395 /404. Haney, M., Ward, A.S., Comer, S.D., Hart, C.L., Foltin, R.W., Fischman, M.W. 2001. Bupropion SR worsens mood during marijuana withdrawal in humans. Psychopharmacology 155, 171 /179. 309 Hart, C.L., Ward, A.S., Haney, M., Foltin, R.W., Fischman, M.W. 2001a. Methamphetamine self-administration by humans. Psychopharmacology 157, 75 /81. Hart, C.L., van Gorp, W.G., Haney, M., Foltin, R.W., Fischman, M.W. 2001b. Effects of acute smoked marijuana on complex cognitive performance. Neuropsychopharmacology 25, 757 /765. Johanson, C.E., Uhlenhuth, E.H. 1980. Drug preference and mood in humans: d -amphetamine. Psychopharmacology 71, 275 /279. Jones, R.T., Benowitz, N.L., Herning, R.I. 1981. Clinical relevance of cannabis tolerance and dependence. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 21, 143s / 152s. Kelly, T.H., Foltin, R.W., Emurian, C.S., Fischman, M.W. 1993. Performance-based testing for drugs of abuse: dose and time profiles of marijuana, amphetamine, alcohol, and diazepam. J. Anal. Toxicol. 17, 264 /272. Kelly, T.H., Foltin, R.W., Emurian, C.S., Fischman, M.W. 1994. Effects of D9-THC on marijuana smoking, dose choice, and verbal report of drug liking. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 61, 203 /211. Kelly, T.H., Foltin, R.W., Emurian, C.S., Fischman, M.W. 1997. Are choice and self-administration of marijuana related to D9-THC content? Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 5, 74 /82. Kreek, M.J. 2000. Methadone-related opioid agonist pharmacotherapy for heroin addiction. History, recent molecular and neurochemical research and future in mainstream medicine. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 909, 186 /216. McLaren, D.S. 1976. Nutrition and its Disorders, second ed.. Churchill Livingstone, New York. McLeod, D.R., Griffiths, R.R., Bigelow, G.E., Yingling, J. 1982. An automated version of the digit symbol substitution test (DSST). Behav. Res. Meth. Instr. 14, 463 /466. Mello, N.K., Mendelson, J.H. 1980. Buprenorphine suppresses heroin use by heroin addicts. Science 207, 657 /659. Mendelson, J.H., Mello, N.K. 1984. Reinforcing properties of oral D9tetrahydrocannabinol, smoked marijuana, and nabilone: influence of previous marijuana use. Psychopharmacology 83, 351 /356. Miller, T.P., Taylor, J.L., Tinklenberg, J.R. 1988. A comparison of assessment techniques measuring the effects of methylphenidate, secobarbital, diazepam, and diphenhydramine in abstinent alcoholics. Neuropsychobiology 19, 90 /96. Richardson, N.R., Roberts, D.C.S. 1996. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J. Neurosci. Meth. 66, 1 /11. Schuster, C.R., Woods, J.H. 1968. The conditioned reinforcing effects of stimuli associated with morphine reinforcement. Int. J. Addict. 3, 223 /231. Shahan, T.A., Bickel, W.K., Madden, G.J., Badger, G.J. 1999. Comparing the reinforcing efficacy of nicotine containing and denicotinized cigarettes: a behavioral economic analysis. Psychopharmacology 147, 210 /216. Smith, S.G., Werner, T.E., Davis, W.M. 1977. Alcohol-associated conditioned reinforcement. Psychopharmacology 53, 223 /226. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services: The Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 1992 /1996. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, Md. Ward, A.S., Comer, S.D., Haney, M., Foltin, R.W., Fischman, M.W. 1997. The effects of a monetary alternative on marijuana selfadministration. Behav. Pharmacol. 8, 275 /286. Wesnes, K., Warburton, D.M. 1983. Effects of smoking on rapid information processing performance. Neuropsychobiology 9, 223 / 229.