The Social Setting of Human Rights

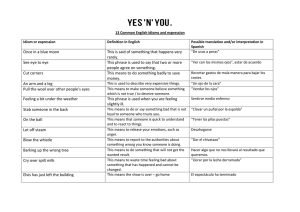

Anuncio