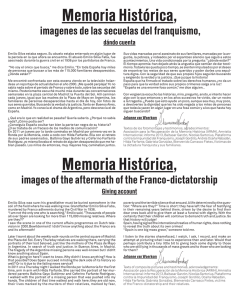

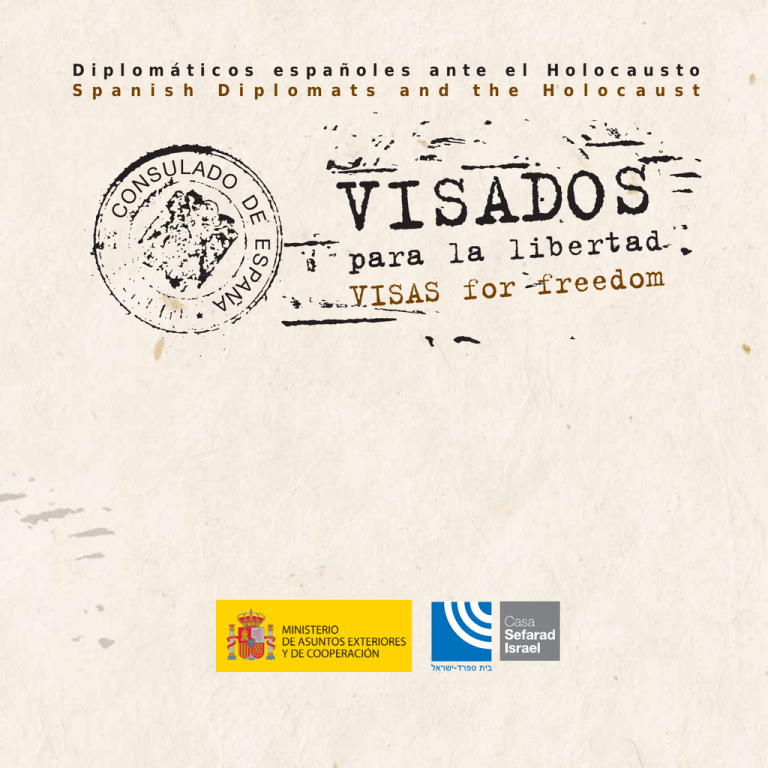

Visados para la libertad

Anuncio