Book Reviews | Reseñas

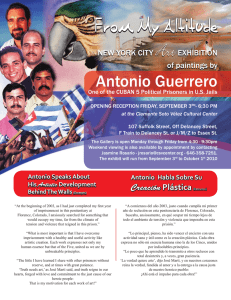

Anuncio