Social Class, Gender, Participation and Lifelong

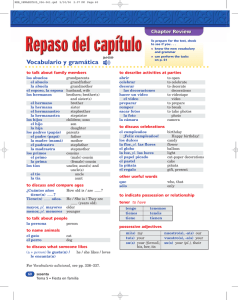

Anuncio