Guía Córdoba Judía/ Jewish Cordoba guidebook

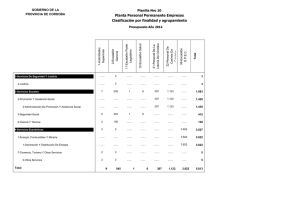

Anuncio