EC consultation Word document

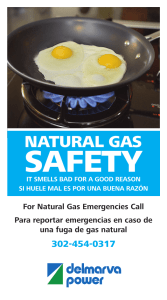

Anuncio