Customers` responses to service failures. Empirical studies on

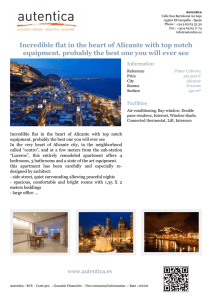

Anuncio

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

•j

LTK'í ERSITAT D' ALAC 'iNT

f-

1

Universitat d'Alacant

Universidad de Alicante

•

c ED 5 P

™1

i

O -1

i

Z ! ~ . L. - - '

I"!

i'IM-

L

TESIS DOCTORAL CON MENCIÓN DE DOCTOR EUROPEO

Alicante, Julio de 2005

Customers' responses to service failures

Empirical studies on prívate, voice and third-party

responses

Ana Belén Casado Díaz

Departamento de Economía Financiera, Contabilidad y Marketing

Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales

Directores:

Francisco J. Mas Ruiz

Catedrático de Comercialización e Investigación de Mercados de la

Universidad de Alicante

J. D.P. Kasper

Professor of Services and Retail Management ofMaastricht University

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

!

,¿

:

•

a

f

¡:

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

A mis padres

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Acknowledgments

This is one of the most exciting moments in my life. I have dreamt many

times the writing this preface (though dreaming of writing it in Spanish) but,

after many years of hard work, here we are. Now, it is time to give recognition

to and to thank all the people that have made this work possible.

With respect to the development of this research, fírst of all, I would like to

express my sincerest gratitude to my co-supervisor Francisco José Mas Ruiz. He

has been crucial in all the stages of this work, giving me not only wise advice

but also his own time and hard work during all these years and, most

importantly, personal support and encouragement in the moments I needed. I

am deeply grateful to him.

Second, I would like to thank Peter S.H. Leeflang for the interest he has

always shown in the completion of this thesis. He introduced me to Hans

Kasper who agreed to be my co-supervisor without knowing anything about me.

Since then, Hans has patiently reviewed my work, giving me wise advice that

has improved this dissertation. I would especially like to thank him for having

made possible my stay at the Department of Marketing and Marketing Research

of Maastricht University. During the three months that I spent there I met

amazing people who shared their valuable knowledge and experience with me

and made my stay easier, and fun. Very special thanks go to Piet Pauwels, Vera

Blazevic, Lisa Deutskens and Sonja Wendel.

Third, I have to mention also my colleague Ricardo Sellers Rubio, co-author

of the study presented in the sixth chapter of this thesis. It has been a pleasure to

work with him and his contribution has been especially valuable with respect to

the implementation of the event study technique. I would also like to thank

Carlos Forner Rodríguez for his help with the bootstrap estimation in this

chapter.

Finally, I would like to thank the Department of Financial Economics,

Accounting and Marketing of the University of Alicante where I have found a

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

great place to work in. I would like to mention especially Juan Carlos Gómez

Sala, Francisco José Mas Ruiz, Joaquín Marhuenda Fructuoso, and Ángel León

Valle, for establishing the appropriate research orientation in the department

that has brought the physical and economic resources necessary to my

formation as researcher. I would like to thank also Juan I. España Valor and

Cristina Girones Ansuátegui for their valuable work, kindness, friendship, and

help; you can always count on them.

Regarding the personal support for developing this thesis, not only have I

found a great place to work; I have also found amazing people to work with at

the Department. I am probably the luckiest worker of this world, loving going to

work just to meet my colleagues: Juan Luis Nicolau (who has always

encouraged me with kind words), Mónica Espinosa (who introduced me in the

select 'morning-coffee group'), Ricardo Sellers, and so on. But especially

important for me are Felipe Ruiz, Paco Poveda, Carlos Forner, and "my" María

Jesús Pastor. They are my particular "sanedrín", my wise and extremely patient

friends. Above all, I want to thank my roommate Felipe for being there every

time I needed him, with his willingness to help/hear me and to make my life

easier. Having met them is one of the best things that has happened to me; no

doubt, they have made me a better person. I wish everyone friends like them!

From now on, I will continué in Spanish.

Me gustaría agradecer a toda mi familia su incondicional apoyo todos estos

años, la paciencia que todos han tenido conmigo, lo fácil que me han hecho la

vida, en resumen, el amor que siento que me tienen y que yo les tengo.

Especialmente quiero mencionar a mis padres, dos personas increíbles con las

que he tenido la suerte de crecer y a las que les debo todas las cosas buenas

que pueda haber en mí. A ellos les dedico esta tesis. A mis hermanos, que

siempre están ahí, apoyándome y escuchándome, son los mejores. A mis

sobrinos, a los que no he podido dedicar todo el tiempo que me habría gustado

en su primer año de vida pero que espero compensar a partir de ahora. A mis

cuñados y a mis suegros, que siempre me han tratado como a una hija más. A

mis tíos/as y primos/as, por el cariño que me han mostrado siempre.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

También quiero mencionar aquí a todos mis amigos por los ánimos que me

han dado durante todo este tiempo, especialmente Dominique, Javi, Natalia,

Jaime, Cristina, Paloma y el resto de la troupe valenciana (supongo que

respirarán aliviados cuando lean esto).

Para terminar, quiero agradecer a Pepe su apoyo, su paciencia, sus

ánimos, las veces que me ha hecho reír, las veces que me ha recordado las

cosas que de verdad importan en esta vida, su aguante infinito durante todos

estos años (sobre todo con las veces que lo he dejado solo), su sonrisa, sus

abrazos, ... supongo que todo.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Julio de 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Table of contents

Chapter 1. Introduction

1.1. SERVICE FAILURES: THE STARTING POINT

1.2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES OF THE DISSERTATION

1.2.1 Objectives Chapter 4

1.2.2 Objectives Chapter 5

1.2.3 Objectives Chapter 6

1.3 DISSERTATION OUTLINE

Chapter 2. Service failures: theoretical considerations

11

11

14

16

17

17

18

21

2.1 INTRODUCTION

2. /. 1 The basic characteristics ofservices

2.1.2 Thefocus on customer satisfaction

21

22

24

2.2 SERVICE FAILURE ENCOUNTERS: DEFINITION AND NATURE

27

2.3 CUSTOMER (DIS)SATISFACTION IN SERVICE FAILURE ENCOUNTERS: DEFINITION

AND NATURE

31

2.3.1 Customer (dis)satisfaction as a response

32

2.3.2 Thefocus ofthe customer (dis)satisfaction response

33

2.3.3 The timing ofthe customer (dis)satisfaction response

34

2.4 ANTECEDENTS/DETERMINANTS OF CUSTOMER (DIS)SATISFACTION IN SERVICE

FAILURE ENCOUNTERS

35

2.4.1 Service features

36

2.4.2 Causal attributions

39

2.4.3 Customer emotions

40

2.4.4 Perceptions ofjustice

44

2.5 OUTCOMES OF CUSTOMER (DIS)SATISFACTION IN SERVICE FAILURE ENCOUNTERS

45

2.5.1 Prívate responses (Chapter 4 context)

47

2.5.2 Voice responses (Chapter 5 context)

48

2.5.3 Third-party responses (Chapter 6 context)

51

Chapter 3. Summary and description ofthe empirical applications

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

53

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

vi • Table of contente

Chapter 4. The consumer's reaction to delays in service

4.1 INTRODUCTION

4.2 THE MODELING OF THE SERVICE DELAY EVALUATIONS AND THE HYPOTHESES

56

56

58

4.2.1 Attribution theory: attribution of control

60

4.2.2 Attribution theory: attribution ofstability

61

4.2.3 Perceivedwaiting time and importance qfsuccessful service performance 62

4.2.4 Anger

65

4.2.5 Satisfaction with service

67

4.3 METHODOLOGY

68

4.3.1 Sample and data collection

68

4.3.2 Development ofmeasures

69

4.4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.4.1 Sample characteristics

4.4.2 Testing the proposed model

4.5 CONCLUSIONS

APPENDIX 4.1 MEASURES EMPLOYED IN THE STUDY

APPENDIX 4.2 DELAY CAUSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

70

71

73

79

80

81

Chapter 5. Anger and distributive justice in a double deviation scenario:

explaining (dis)satisfaction in service failure and failed recovery contexts

83

5.1 INTRODUCTION

5.2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK AND RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

83

86

5.2.1 Service failure and failed recovery: a double deviation scenario

88

5.2.2 Determinants of (dis)satisfaction in a double deviation context

89

5.2.2.1 Direct effects and indirect effects, through cognitive and emotional antecedente,

of service failure-related variables

90

5.2.2.2 Indirect effects of service recovery-related variables through cognitive and

emotional antecedente

95

5.2.2.3 Direct and indirect effects of cognitive and emotional antecedente

99

5.3 METHODOLOGY

104

5.3.1 Sample and data collection

104

5.3.2 Development ofmeasures

106

5.3.3 Data analysis

109

5.3.3.1. General data analysis procedure

109

5.3.3.2 Analysis of the measurement models

110

5.4 RESULTS

113

5.4.1 Direct effects and indirect effects, through cognitive and emotional

antecedents, of service failure-related variables

116

5.4.2 Indirect effects, through cognitive and emotional antecedents, of service

recovery-related variables

118

5.4.3 Direct and indirect effects of cognitive and emotional antecedents

119

5.5 DISCUSSION

5.6 CONCLUSIONS

APPENDIX 5.1 MEASURES EMPLOYED IN THE STUDY

APPENDIX 5.2 FORMULATION OF MEASUREMENT AND STRUCTURAL MODELS

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

120

125

127

128

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Table of contents • vii

Chapter 6. Third-party complaints and banking market valué: the moderating

effects of quality corporate image and market concentration

131

6.1 INTRODUCTION

6.2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK AND RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

131

133

6.2.1 Relationship between thefirm 's appearance in the Annual Report on

Complaints andthefirm 's performance

755

6.2.2 Moderating effect of quality corporate image on the relationship between

thefirm 's appearance in the Annual Report on Complaints and thefirm 's

performance

136

6.2.3 Relationship between the number of third-party complaints andthefirm 's

performance

139

6.2.4 Moderating effect of market concentration on the relationship between the

number of third-party complaints and thefirm 's performance

141

6.3 METHODOLOGY

143

6.5.7 Sample

143

6.3.2 Analysis procedures

144

6.3.3 Data collection and measurement

149

6.3.4 Consumer complaint procedure

152

6.4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

153

6.4.1 Estimation ofreturn variation resultingfrom thefirm 's appearance in the

Annual Report on Complaints

153

6.4.2 Determinants ofreturn variation

156

6.4.2.1 Moderating effect of quality corporate image and direct effect of the number of

third-party complaints

156

6.4.2.2 Moderating effect of target market concentration

158

6.5 CONCLUSIONS

159

APPENDIX 6.1 P-VALÚES OBTAINED WITH BOOTSTRAP ESTIMATION

161

Chapter 7. Conclusión: summary, implications, limitations and future research 163

7.1 SYNOPSIS

7.2 THE CONSUMER'S REACTION TO DELAYS IN SERVICE

7.2.1 Main results and conclusions

7.2.2 Managerial implications

7.2.3 Limitations and future research

7.3 ANGER AND DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE IN A DOUBLE DEVIATION SCENARIO

7.5.7 Main results and conclusions

7.3.2 Managerial implications

7.3.3 Limitations and future research

7.4 THIRD-PARTY COMPLAINTS AND BANKING MARKET VALUÉ

7.4.1 Main results and conclusions

7.4.2 Managerial implications

7.4.3 Limitations and future research

7.5 FINAL CONCLUSIÓN

163

169

769

770

777

171

777

772

174

176

7 76

777

178

179

References

183

Resumen de la tesis doctoral

211

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Chapter 1

Introduction

In this chapter, we first introduce and describe the field this dissertation is

about. Next, we discuss the general research objectives as well as the specific

objectives of the individual studies. Finally, we conclude with an outline of the

remainder of this dissertation.

1.1. Service failures: the starting point

The understanding of the consequences of service failures is a key factor in

the strategic management of a service firm. Even the most customer-oriented

culture and the strongest quality program will not entirely eliminate mistakes

during service delivery (Kelley and Davis, 1994). Despite all the procedures,

some things may go wrong, especially since delivering services requires human

interaction. There is a popular saying: people may make or break the service.

Therefore, during the last years, service firms have made numerous attempts to

develop different strategies to deal with service failures (e.g., training

employees, starting customer affairs departments) with a double objective: to

prevent the same failure to occur again and to recover customers who complain

from their initial dissatisfaction. Thus, understanding the different elements that

affect (dis)satisfaction after service failure and subsequent behaviors derived

from this (dis)satisfaction can be useful for service managers to reduce the

impact of failures on firm performance.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

12 « Chapter 1

While the issue of consumer dissatisfaction is of importance to marketers in

general, some underlying characteristics of services make the topic especially

critical for services marketers. First, services are, to a greater degree than goods,

intangible, heterogeneous, and simultaneously produced/distributed and

consumed (Zeithaml et al., 1993). Second, in the performance of services both

customers and service personnel play a role (Solomon et al., 1985). These

characteristics increase the likelihood of errors (service failures) in the service

área both from an operational perspective as well as from the customer's

viewpoint and, therefore, increase the need for recovery (Brown et al., 1996).

Thus, service failure is defined as a customer's problem with a service

(Spreng et al., 1995) and is said to occur when the service experience falls short

of customer's expectations (Bell and Zemke, 1987). Traditionally, the service

literature considers failures to be inevitable or as Hart et al. (1990) stated

"mistakes are a critical part of every service" (p. 148). These failures in service

quality lead to dissatisfaction.

Existing research on customer (dis)satisfaction after a service failure occurs

can be divided into three major groups: (1) studies on the main antecedents and

consequences of customer (dis)satisfaction after service failure (e.g., Oliver,

1997; Westbrook, 1987), (2) studies on the main antecedents and consequences

of customer (dis)satisfaction after service failure and recovery (e.g., Smith et al.,

1999; Tax et al., 1998), and (3) studies on the main antecedents and

consequences of customer dissatisfaction response styles (e.g., Singh, 1988).

Different theories are behind the development of these studies such as the

expectancy-disconfírmation paradigm (Oliver, 1981), equity theory (Clemmer

and Schneider, 1996), emotion/affect theory (see Bagozzi et al., 1999, for a

review), or attribution theory (Weiner, 1985).

When a service failure occurs customers may respond in a variety of ways

from doing nothing at all to suing the company for millions of euros. This

process begins when the customer has evaluated a consumption experience and

ends when the customer has completed all behavioral and/or non-behavioral

responses to the experience (Day, 1980).

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Introduction

•

13

Different taxonomies have been proposed to analyze the ways used to

express dissatisfaction (e.g., Day, 1980; Day and Landon, 1977; Richins, 1983,

1987; Singh, 1988). In this dissertation, we center on the framework proposed

by Singh (1988) which brings together the three empirical applications we have

carried out in a very clear and comprehensible manner. Singh (1988)

empirically proposed and tested a taxonomy in four different service categories:

grocery shopping, auto repair, medical care, and fínancial services. Thus, when

dissatisfaction occurs, three types of responses are likely to occur (see Figure

1.1): prívate response (e.g., repurchase intentions and/or word of mouth

communication to friends and relatives), voice response (e.g., seeking redress

from the seller and/or not taking any action), and third-party response (e.g.,

taking legal action and/or fíling a complaint with a Better Business Bureau). In

these three categories, there is a progression of the amount of effort involved in

complaining. For example, the prívate party objects are neither external to the

consumer's social network ñor are they directly involved in the dissatisfying

experience; the voice response (including no action or boycott) is primarily

directed against the seller; and the third party responses are directed toward

seeking redress from organizations (or courts) not directly involved in the

dissatisfying experience. Each of these three responses will receive full

attention in the theoretical and empirical part of this dissertation.

In the next section, we specifically address the overall objectives of this

dissertation and the specific objectives of the three studies we have carried out.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

14 « Chapter 1

Figure 1.1

Dissertation contextualization adapted from Singh's (1988) taxonomy

<

Dissatisfaction occurs:V

SER FICE FAIL

URE/

PRÍVATE

RESPONSES

(e.g., repurchase

intentions)

^

VOICE

RESPONSES

(e.g., redress seeking)

^_

Y

Specific context of

Chapter 4

Y

Specific context of

Chapter 5

THIRD PARTY

RESPONSES

(e.g., complain to a

public agency)

k_

"V

J

Specific context of

Chapter 6

Amount ofejfort involvedin complaining

+

1.2 Research objectives of the dissertation

The overall motivation behind this research is driven by the importance of

service failures in daily life, for firms as well as for customers. Therefore, the

aim of this dissertation is to contribute to the theoretical and empirical evolution

of service failures' research toward a better understanding of their

characteristics and, consequently, their implications for management. This

overall objective is divided into the following three general research questions.

The first two questions are examíned in the first two empirical applications

(Chapters 4 and 5), whereas the last question is dealt with in the third empirical

application (Chapter 6).

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Introduction

•

15

Research Question 1. Which are the main variables that affect specific

customers' responses after a service failure (Le., prívate and voice responses)

and subsequentjudgments and/or behaviors?

We use empirical data to examine the main antecedents and consequences of

a dissatisfying experience following a specific service failure. In the first study

(Chapter 4), our service context is the airline industry and the service failure is a

flight delay. The second study (Chapter 5) is conducted in the banking industry

and the service failure is a banking failure. Using literature from a variety of

disciplines, such as marketing and (social) psychology, we first formúlate a

conceptual framework for every study. Subsequently, the substantive

relationships in these frameworks are tested.

Research Question 2. Which is the role played by negative emotions (Le.,

anger) vs. cognitive evaluations in customers' judgments and/or behaviors

following a service failure?

In the first two empirical applications (Chapters 4 and 5), we outline the

importance of studying the role of specific emotions in the formation of the

(dis)satisfaction judgment in a service failure context and, specifically, the role

of the negative emotion of anger. This focus on one specific emotion (i.e.,

anger) is in line with recent literature that focuses on the idiosyncratic elements

of specific emotions (Bougie et al., 2003; Louro et al., 2005; Tsiros and Mittal,

2000; Zeelenberg and Pieters, 2004). Accordingly, more insight into the specific

antecedents, phenomenology and consequences of different emotions (such as

anger) is needed (Lings et al., 2004). However, little attention has been paid to

the study of anger as the most frequent emotional reaction that arises in the

service failure contexts and its influence on customer's prívate (e.g., repurchase

intention) and voice (e.g., seeking redress from seller) responses. Specifically,

we examine the role of anger vs. different cognitive elements in the proposed

models.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

I

16 '

Chapter 1

Research Question 3. Do customers' third-party responses affect firm

performance?

In the third empirical application (Chapter 6), we examine the effect of thirdparty responses to service failures on firm performance. ín this study, we focus

on the investor's perspective, thus incorporating the financia! side into the

traditionai marketing view. Specifically, we use literature from different

disciplines, such as marketing, financial economics and signaling theory, for the

formulation of a conceptual framework. Then, the substantive relationships in

this framework are empirically tested.

To address these overall research questions effectively, we next formúlate

specific objectives for the different chapters in which we address the previous

three general problem statements from different perspectives.

1.2.1 Objectives Chapter 4

In Chapter 4, we focus on the airline industry to examine the impact of a

flight delay on the initial (dis)satisfaction judgment and subsequent behavioral

and complaining intentions {prívate responses). The objectives of this chapter

are: 1) to develop and empirically test a comprehensive conceptual framework

grounded in several research flelds that identifies the antecedents and

consequences of the (dis)satisfaction with the service failure (i.e., the flight

delay), 2) to examine the impact ofthe specific negative emotion of anger on the

previous framework, and 3) to explore the effects of different service-failure

related variables on (dis)satisfaction with service and on behavioral and

complaining intentions directly and indirectly through anger and

(dis)satisfaction with service.

As a new element, we jointly examine anger (emotional reaction) and

(dis)satisfaction with service failure (cognitive and emotional evaluation). Thus,

we analyze the impact of the initial negative emotion of anger on the initial

(dis)satisfaction judgment and subsequent behavioral and complaining

intentions.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

lntroduction • 17

1.2.2 Objectives Chapter 5

In Chapter 5, we go a step further and analyze the impact of a secondary

negative emotion (anger with service recovery) on secondary satisfaction

judgments (satisfaction with service recovery), in the specific context of double

deviation scenarios. In contrast to Chapter 4 which was centered on private

responses of customers, we base this research on voice responses of customers.

This means that we analyze data from customers who have complained to the

fírm after the service failure (i.e., they have voiced their dissatisfaction). From

these customers, we center on those who have experienced a failed recovery

after the initial service failure (i.e., double deviation). The objectives of this

chapter, which is focused on the banking industry, are: 1) to develop and

empirically test a comprehensive conceptual framework grounded in several

research flelds that identifles the antecedents of the (dis)satisfaction with

service recovery in the specific context of double deviation scenarios (i.e., failed

recoveries after service failures), 2) to examine the role of the secondary

emotion of anger (i.e., anger with service recovery) and the distributive

component ofjustice on the previous framework, and 3) to explore the direct

and indirect effects of service failure and service recovery-related variables on

(dis)satisfaction with service recovery judgments through the secondary

emotion of anger with service recovery and through the distributive justice

component.

The few studies in the service failure and recovery context that include

emotions in their proposals are centered on the emotions triggered by the initial

service failure (e.g., Andreassen, 2000; Bougie et al., 2003; Dubé and Maute,

1996; Smith and Bolton, 2002). Thus, this is the first attempt to model the effect

of specific secondary emotions on secondary (dis)satisfaction. It is also the first

attempt to empirically test a model of (dis)satisfaction with service recovery in

double deviation scenarios.

1.2.3 Objectives Chapter 6

In Chapter 6, we examine the impact of third-party complaints on company

performance. As in Chapter 5, we focus on the banking industry. Specifically,

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

18 • Chapter 1

we examine the complaints from the Bank of Spain's Complaints Service (the

third party), which publishes an Annual Report on Complaints to Spanish

banks. We propose that the reléase of this information about third-party

complaints is economically relevant to the stock market. The objectives of this

chapter are: 1) to determine the economic impact for the banks involved, in

terms of variation in stock prices, of appearing on the Annual Report on

Complaints ofthe Bank ofSpain 's Complaint Service, and 2) to examine to what

extent the variations in stock prices can be explained through the number of

complaints received by the bank in the Annual Report, the quality corporate

image, and the target market concentraron.

Until now, the influence of customer's third-party responses has been

analyzed from a customer perspective but not on the basis of its impact on firm

performance.

1.3 Dissertation outline

Chapter 2, Service failures: theoretical considerations, examines different

theoretical issues concerning the service failures. After defíning the basic

concepts, the antecedents of customer (dis)satisfaction in service failure

encounters are reviewed, focusing on the ones employed in this dissertation.

Finally, we present the outcomes of customer (dis)satisfaction in service failure

encounters following the taxonomy proposed by Singh (1988).

Chapter 3, Summary and description of the empirical applications, briefly

outlines the variables employed in the three empirical applications and how they

relate to the theoretical dimensions analyzed in Chapter 2. The main objective

of this short chapter is to give the reader a quick but complete view of what is

being studied in each ofthe empirical studies.

Chapter 4, The consumer's reaction to delays in service, centers on the

relationships that exist among attributions of control and stability, service features'

perceptions (perceived waiting time and punctuality importance), anger emotion,

(dis)satisfaction, and repurchase and complaining intentions of customers who

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Volver al Indice/Tornar a l'índex

Iníroduction

•

19

suffer delays in flights (airline industry). Thus, the service failure in this study is a

flight delay and the response examined is prívate.

Chapter 5, Anger and distributive justice in a double deviation scenario:

explaining (dis)satisfaction in service failure and failed recovery contexts,

analyzes the underlying mechanisms which contribute to (dis)satisfaction

formation in double deviation scenarios (i.e., failed recovery after service

failure). Accordingly, we propose and empirically test a framework that outlines

the roles of distributive justice (cognitive antecedent) and anger (emotional

antecedent) in determining (dis)satisfaction with service recovery (postrecovery attitude). Additionally, we examine how specifíc service failure and

service recovery-related variables influence customer (dis)satisfaction with

service recovery directly and/or indirectly through the cognitive and emotional

antecedents. This framework is applied to a cross-sectional sample of

dissatisfied banking customers (banking industry). Therefore, the service failure

in this study is a failed recovery and the response examined is the voice response.

Chapter 6, Third-party complaints and banking market valué: the

moderating effects of quality corporate image and market concentration,

examines the impact of third-party complaints on fírm performance.

Specifically, we analyze how the stock market (investors) reacts to the Annual

Report on Complaints to Spanish banks published by the Bank of Spain's

Complaints Service (the third-party). Additionally, we investígate the

explanatory power of the number of complaints received by the bank in the

Annual Report and the moderating roles played by quality corporate image and

market concentration. In sum, the service failure in this study is a failed recovery

and the response examined is the third-party one.

Finally, in Chapter 7, Conclusions: summary, implications, limitations and

future research, we provide a summary of the main theoretical and managerial

contributions, limitations, and directions for future research, of the three

empirical applications presented in this dissertation.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Chapter 2

Service failures: theoretical considerations

In this chapter, we examine the specific concepts, variables, and empirical

contexts that will be applied in the three applications discussed later in this

dissertation. Although each of these studies thoroughly reviews the existing

literature to define the study context and the variables employed, we feel that a

more general chapter will contribute to getting a broad perspective of the whole

present research.

2.1 Introduction

Services domínate most developed countries and, in the particular case of

most countries in the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and

Development), the service sector accounts for 70% or more of aggregate

production and employment and continúes to grow (Wolfl, 2005). This growing

importance of the service sector has contributed to the development, over the

last three decades, of services marketing management (also known as services

marketing and/or services management) which has embraced other disciplines

such as human resources and operations (Swartz and Iacobucci, 2000).

Building on previous works in services marketing literature, Kasper et al.

(1999) propose the following defínitions of services:

'''Services include all economic activities whose output is not a physical

product or construction, is generally consumed at the time it is produced, and

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

22 » Chapter 2

provides added valué in forms (such as convenience, amusement, timeliness,

comfort or health) that are essentially intangible concerns ofitsfirst parchase"

(P-9)

"Services are originally intangible and relatively quickly perishable

activities whose buying takes place in an interaction process aimed at creating

customer satisfaction but during this Interactive consumption this does not

always leadto materialpossession" (p. 13)

Two main issues arise from the above definition: fírst, there are certain

characteristics that seem to differentiate services from goods and, second, in

line with authors such as Zeithaml and Bitner (2000), it seems that customer

satisfaction is the ultimate goal of service fírms. In the next subsections, we go

deeper into both aspects: the basic characteristics of services and the focus on

customer satisfaction.

2.1.1 The basic characteristics of services

Regarding the distinction between services and goods, from the early works

centered on the questions of 'if and 'how' services differed from goods, we

carne to the classic distinction between goods and services, based on the 4 I's:

intangibility, inseparability (as a degree of simultaneous production and

consumption), inconsistency (as a degree of heterogeneity), and inventory (as a

degree of perishability) of services compared to goods (Shostack, 1977).

The intangibility feature is the most dominant one in defíning services and

determines the other three characteristics (Kasper et al., 1999). However, the

differentiation between goods and services in terms of this feature is not easy.

Service organizations are trying to make tangible their intangible offer (and

even, many services can not be provided without tangibles), while many

manufacturers try to créate an (intangible) image around their goods.

Due to the intangibility, in many instances, customers find it hard to evalúate

services in advance. Furthermore, customers often cannot predict the outcome

of a service experience. These two aspects are strongly related with the risk

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Service failures: theoretical considerations • 23

customers perceive in buying and using particular services. The literature

differentiates eight types of perceived risk: financial uncertainty (whether

customers pay more than they should); functional uncertainty (whether the

service really offers what it should); physical uncertainty (safety of the service

delivery); social uncertainty (the way in which the environment of the customer

will react to the choice of a certain service or particular service provider);

psychological uncertainty (the way in which a bad choice will damage the

image of the customer); life style uncertainty (similar to the social and

psychological uncertainty but especially focused on the expected or actual

consequences for one's own life style); time uncertainty (whether the time spent

searching for a service is wasted when the chosen service or service provider

does not perform according to expectations); and, environmental uncertainty

(the possible damage that the service or service delivery process may cause to

the environment). Generally, the (customer's total) perceived risk in a purchase

situation implies a mixture of these eight different kinds of uncertainty and it

can vary among services or service delivery processes. In any case, the

customer's perceived risk affects the way customers evalúate service

performance, also in service failure situations. The perceived risk is higher for

'fírst time buys' compared to 'repeated buys' due to customers' higher

uncertainty when consuming the service for the fírst time.

The second T , inseparability, or the degree of simultaneous production and

consumption, means that transferring the service usually requires the presence

and participation (i.e., the interaction) of the customer. This interaction may be

referred to as 'the service encounter', and can be mainly affected by the

environment in which the process of producing and consuming the service takes

place, the personnel involved, and the customer.

The third T , inconsistency, or the degree of heterogeneity, arises from the

active participation of the customer in the process of producing and consuming

the service, which makes the standardization of services quite diffícult.

Automation may reduce the impact of people and the environment on service

quality. However, there is still the problem that not only objective and/or

technical issues are evaluated by the customer but also subjective elements as

well as the amount of time used.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

24 » Chapter 2

Finally, inventory (the fourth T ) , or the degree of perishability, means that

usually services cannot be kept in stock. This reduces costs of warehousing, but

it also makes it difficult to face fluctuations in demand or in capacity.

Therefore, waiting is typical for service delivery processes. Probably,

information technology will contribute to better serve the customer in this sense.

2.1.2 The focus on customer satisfaction

Customer satisfaction, as the ultímate goal and the primary obligation of

service firms, is a defensible and appropriate company objective which allows

holding various corporate functions together and directs corporate resource

allocation (Zeithaml and Bitner, 2000).

Conceptually, virtually all company activities, programs, and policies should

be evaluated in terms of their contribution to satisfying customers (Peterson and

Wilson, 1992)1. The reason is that individual firms have discovered that

increasing levéis of customer satisfaction ('delight' customers) can be linked to

customer loyalty and profits (Anderson et al., 1997; Heskett et al., 1997).

Differently stated, many firms have adopted a retention/relationship focus

(relationship marketing/management) whose primary goal is to build and

maintain a base of committed customers who are profítable for the organization

(Zeithaml and Bitner, 2000). To achieve this goal, the service firm should focus

on the attraction, retention, and enhancement of customer relationships (Berry,

1983) through the effective satisfaction of customers' requirements, that is,

through the provisión of sufficient service quality.

However, quality is an ambiguous term which can be viewed from many

different points of view. Therefore, Garvín (1988) formulates five approaches to

1

In fact, because of the importance of customer satisfaction to firms and overall quality of life,

many countries have a national índex that measures and tracks customer satisfaction at a macro

level. Many public policymakers believe that these measures could and should be used as tools

for evaluating the health of the nation's economy, along with traditional measures of productivity

and price. These indexes include the quality of economic output, while more traditional economic

indicators tend to focus only on quantity (Zeithaml and Bitner, 2000). Some examples are the

Deutsche Kundenbarometer (DK) in Germany, the Swedish Customer Satisfaction Barometer

(SCSB) in Sweden, or the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) in United States of

America.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Service failures: theoretical considerations • 25

studying quality in the context of tangible products: transcendent (psychology),

product-based (economics), user-based (marketing and operational

management), manufacturing-based (operational management), and valuebased. Kasper et al. (1999) have applied these approaches to the service context.

Thus, the transcendent approach implies that quality cannot always be defíned

and is partly a matter of experience. The product-based approach views quality

as a measurable and objective variable, in terms of the level of services or

features offered. The user-based approach bases on the customer's judgment,

which is largely subjective and leads to perceived service quality. The

manufacturing-based approach views quality as an objective and measurable

term and mainly concerns conformance to requirements (in technical

terms/specifications). Finally, the value-based approach considers quality in

relation to cost and price.

From these different perspectives, we focus on the user-based approach to

service quality. Following Kasper et al. (1999), quality of a service is often a

perceived quality, depending mostly on expectations and the way the service is

received. Therefore, Kasper et al. (1999) define quality as "the extent in which

the service, the service process and the service organization can satisfy the

expectations of the user" (p. 188)2. Putting the customers' satisfaction at the

center of services marketing implies that their subjective evaluations are

decisive in their evaluation of the organization's performance. Therefore,

marketing managers have to pay attention to the expectations of customers (to

properly achieve their requirements) and to their quality perceptions.

In evaluating service quality, customers focus on different attributes that

may differ per service. Consequently, different studies have made an attempt to

come up with a bundle of features that are always (or almost always) present in

customers' evaluations of service quality. The first result in this sense was the

2

In searching for information from a particular service or service organization, customers may

use various characteristics, attributes or qualities of services. Often, three kinds of search

attributes/qualities are distinguished (Zeithaml and Bitner, 2000): search, credence, and

experience attributes. Search attributes are easy to judge by the customer before the service

delivery actually takes place and usually involve tangible aspects. Credence attributes can only be

judged after the actual service delivery and are based on trusting people delivering the service.

Finally, experience attributes are in the middle of the previous two types, being difficult to

evalúate in advance and experienced only after the service delivery. In general, perceived risk will

be greater the less search attributes and the more experience and credence attributes are at stake

(Kasper et al., 1999, p. 156).

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

26 • Chapter 2

qualitative study of Parasuraman et al. (1985). The authors identified ten

determinants of service quality (Parasuraman et al., 1985, p. 47): reliability (i.e.,

consistency of performance and dependability), responsiveness (i.e., willingness

or readiness of employees to provide service), competence (i.e., possession of

the required skills and knowledge to perform the service), access (i.e.,

approachability and ease to contact), courtesy (i.e., politeness, respect,

consideration, and friendliness of contact personnel), communication (i.e.,

keeping customers informed in language they can understand and listening to

them), credibility (i.e., trustworthiness, believability, honesty, having the

customer's best interests at heart), security (i.e., the freedom from danger, risk,

or doubt), understanding/knowing the customer (i.e., making the effort to

understand the customer's needs), and tangibles (i.e., physical evidence of the

service).

Later, the authors developed a 22-item instrument (called SERVQUAL),

which recast the ten previous determinants into five specific components (three

original and two combined dimensions): tangibles (i.e., physical facilities,

equipment, and appearance of personnel), reliability (i.e., ability to perform the

promised service dependably and accurately), responsiveness (i.e., willingness

to help customers and provide prompt service), assurance (i.e., knowledge and

courtesy of employees and their ability to inspire trust and confidence), and

empathy (i.e., caring, individualized attention the firm provides its customers)

(Parasuraman et al., 1988:23). These are general dimensions which can be

found in most services and that reflect customers' subjective judgments about

the valué received by service performance (Kasper et al., 1999, p. 213)3.

3

After the publication of the Parasuraman et al.'s (1988) study on SERVQUAL, numerous

studies have examined critically their model, especially the works of Joseph Cronin and Stephen

Taylor (Cronin and Taylor, 1992, 1994). The basic criticisms concern: the need of measuring

expectations, how expectations are measured, the dimensionality of SERVQUAL, or the number

of items in the SERVQUAL scale, among other issues (Kasper et al., 1999, p. 224). Based on

these criticisms, Cronin and Taylor (1992; 1994) developed an altemative method of

operationalizing perceived service quality, the SERVPERF-model. The main difference wíth the

SERVQUAL-model is that they only use questions about performance (i.e., perception), ignoring

the questions about expectations.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Service failures: theoretical considerations • 27

In sum, the focus on customer satisfaction logically draws attention to the

management of individual service encounters4 between the ultimate customer

and representatives of the firm (Bitner et al, 1990), sometimes referred to as

'moments of truth' (Carlzon, 1987). It is in these moments of truth, when the

customer interacts with the service firm, that the service quality is most

immediately evident to the final customers. Each service encounter pro vides an

opportunity for the firm to reinforce its commitment to customer satisfaction

and/or to service quality and can potentially be critical in determining customer

satisfaction and loyalty. Additionally, each individual encounter is important in

creating a composite image of the firm in the customer's memory. Over time, it

is likely that múltiple positive (negative) encounters will lead to an overall high

(low) level of satisfaction (Bitner and Hubbert, 1994).

However, as stated before, even the most customer-oriented culture and the

strongest quality program may not entirely eliminate mistakes during service

delivery (Kelley and Davis, 1994). Service encounters can often produce

negative reactions despite the service personnel trying to do their very best

(Zeithaml et al., 1985). These critical encounters can ruin the customer-firm

relationship and drive the customer away, no matter how many or what type of

encounters have occurred in the past (Zeithaml and Bitner, 2000). Therefore,

deeper examination of these 'critical' encounters is needed, providing the global

objective of this dissertation.

2.2 Service failure encounters: defínition and nature

The term we use to define a customer's problem with a service is 'service

failure' (Spreng et al., 1995). Service failures occur when the service experience

falls short of customer's expectations (Bell and Zemke, 1987). Or as stated by

Bitner et al. (1990), service failures are specific events that lead to dissatisfying

service encounters from the customers' point of view.

Marketing research on service failures distinguishes two broad types of

failures or losses customers may experience: core service failures (outcome) and

4

The service encounter has been defíned as that period of time during which the consumer and

service firm interact in person, over the telephone, or through other media (Shostack, 1985).

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

28 • Chapter 2

service delivery failures (process) (Bitner et al., 1990; Hoffman et al., 1995;

Keaveney, 1995). Outcome failures refer to actual performance of the basic

service need whereas process failures refer to the customer's experiences while

the service is being performed. Therefore, service encounters, due to their

specific nature, account for both outcome and process dimensions and a failure

could occur along either dimensión. Table 2.1 provides a summary of the main

findings regarding the classification of service failures.

In this dissertation, we analyze both types of service failures. In the first

study (Chapter 4), customers are faced with an outcome service failure, that is, a

delay in their flights. In the next two studies (Chapters 5 and 6), different

service failures are reported, both outcome and process service failures.

Additionally, service failure is assumed to result in dissatisfaction (Zeithaml

and Bitner, 2000), which affects negatively customer retention (e.g., Rust and

Zahorik, 1993), and subsequently has a negative impact on revenue and

profítability (e.g., Fornell and Wernerfelt, 1987, 1988; Rust et al., 1995). As

Hart et al. (1990) stated "mistakes are a critical part of every service, [...] errors

are inevitable [...] but dissatisfíed customers are not" (p. 148). It is the

company's service recovery systems (or the lack of them) that may become a

source of satisfaction or dissatisfaction (Bitner et al., 1990), not necessarily the

mistake or failure itself. However, service providers can not remedy customer's

service failure experiences unless the customer first seeks redress (Blodgett et

al., 1995). This means that complaints lodged directly with the firm are the only

responses that provide the organization with an opportunity to recover

effectively from service failure (Tax et al., 1998).

Specifically, research has shown that firms should invest more resources to

facilitate complaints and encourage dissatisfíed customers to voice their

dissatisfaction through complaints (Fornell and Wernerfelt, 1987). This type of

dissatisfaction management can be an effective tool for customer retention,

particularly in high competitive markets (Fornell and Wernerfelt, 1987, 1988).

Taking into account that today's customers are more demanding, better

informed, and more assertive when service problems arise (Hoffman et al.,

1995, p. 49), many service organizations have developed different strategies to

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Service failures: theoretical considerations • 29

deal with service failures, especially in terms of making the complaining

process as simple as possible (e.g., toll-free cali centers, e-mail).

As said, given the importance of service failures for firms, the main goal of

this dissertation is to examine the harmful consequences of service failures in

three different stages of the customer-firm relationship. In the fírst stage

(analyzed in Chapter 4), we examine the consequences of a service failure, in

terms of customer's satisfaction and behavioral intentions (prívate response). At

this stage, the service firm has not an opportunity to respond to the failure

because the customer's response is prívate. In the second stage (analyzed in

Chapter 5), we investígate the fírm's reaction to service failure (service

recovery) but in the specific context of a failed recovery, that is, when the

service firm fails to recover the customer once he/she has complained (voice

response). Finally, in the third stage (analyzed in Chapter 6), we go a step

further and address third-party responses derived from failed recoveries

(following a service failure). Thus, we examine how third-party responses can

damage fírm's performance not only from a customer basis but also from a

fínancial basis (stock prices).

Therefore, our focus in this dissertation is on what actually happens after

customers experience a service failure (service failure encounter and/or failed

recovery encounter). In the rest of this chapter we center on the main

antecedents and consequences of customer (dis)satisfaction. First, however, we

define what we understand by customer (dis)satisfaction in service failure

encounters.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

30 • Chapter 2

Table2.1

Summary of the main findings regarding the classifícation of service failures

Source

Bitneretal. (1990)

Kelley et al. (1993)

Hoffman et al. (1995)

Lewis and

Spyrakopoulos (2001)

Michel (2001)

Hoffman et al. (2003)

First (priman) failure classifícation

• Gl: employee response to service delivery

system failures

• G2: employee response to customer needs

and requests

" G3: unprompted and unsolicited employee

actions

Bitneretal. (1990):

Gl: employee response to service delivery

system failures

G2: employee response to customer needs

and requests

G3: unprompted and unsolicited employee

actions

Bitneretal. (1990):

Gl: employee response to service delivery

system failures

G2: employee response to customer needs

and requests

G3: unprompted and unsolicited employee

actions

G1: Banking procedures

G2: Mistakes

G3: Employee behavior and training

G4: Functional/technical failures

G5: Actions or omissions of the bank that are

against the sense of fair trade

Gl: Advice

G2: Process

G3: Interaction

G4: Documents

G5: Information

G6: Conditions

G7: Systems

G8: 3rd parties

Bitneretal. (1990):

Gl: employee response to service delivery

system failures

G2: employee response to customer needs

and requests

G3: unprompted and unsolicited employee

actions

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Industry

analyzed

Airlines

Hotels

Restaurants

Retail

Restaurants

Retail banking

Retail banking

Hospitality

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Service failures: theoretical considerations • 31

2.3 Customer (dis)satisfaction

defmition and nature

in

service

failure

encounters:

Despite extensive research during the last decades, researchers have not yet

developed a consensual defmition of customer (dis)satisfaction (Babin and

Griffin, 1998; Oliver, 1997)5. Marketing literature shows different conceptual

and operational definitions of (dis)satisfaction. This basic defínitional

inconsistency is evident by the debate of whether (dis)satisfaction is a process

or an outcome (Parker and Mathews, 2001; Ruyter et al., 1997; Yi, 1990). Thus,

some (dis)satisfaction definitions have emphasized the (evaluation) process

perspective (e.g., Bearden and Teel, 1983; Day, 1984; Fornell, 1992; Fournier

and Mick, 1999). This approach is based on the expectancy disconfirmation

paradigm (Oliver, 1980), and concentrates on the antecedents to

(dis)satisfaction rather than (dis)satisfaction itself. Thus, (dis)satisfaction is

viewed as an evaluative process derived from the global consumption

experience with unique measures capturing unique components of each stage.

This approach seems to draw more attention to perceptual, evaluative, and

psychological processes that combine to genérate consumer satisfaction (Yi,

1990). Additionally, some (dis)satisfaction definitions view this construct as a

response (outcome) to an evaluative process (e.g., Halstead et al., 1994; Oliver,

1997, 1981). That approach focuses on the nature (not cause) of (dis)satisfaction

and proposes that (dis)satisfaction is a result derived from the evaluation of a

specific consumption experience. We will follow this approach in the present

research.

Given the complex nature of satisfaction, it is difficult to develop a generic

global defmition. Rather, the defmition of satisfaction must be contextually

adapted (Giese and Cote, 2000). Therefore, based on a review of the literature

and their own research, Giese and Cote (2000) identify three general

components present in all definitions of (dis)satisfaction:

•

•

consumer (dis)satisfaction is a response (emotional, cognitive, or both);

the response pertains to a particular focus (expectations, product,

consumption experience, etc.); and,

5

For a recent review of the reported evidence on customer satisfaction, see Szymanski and

Henard (2001).

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

32 * Chapter 2

•

the response occurs at a particular time (after consumption, after choice,

based on accumulated experience, etc).

The previous context-specifíc definition refers to service encounter

(dis)satisfaction as opposed to overall service (dis)satisfaction in terms of the

classification made by Bitner and Hubbert (1994)6. Moreover, this definition

captures the complete domain of (dis)satisfaction and is consistent with the

conceptual domain of other researchers (Giese and Cote, 2000). Therefore, the

context-specifíc definition will be our approach in the first two studies carried

out (Chapters 4 and 5) which are the ones that explicitly examine this variable.

In these studies, we adapt the context-specifíc definition to the different

research settings.

Next, we examine the three components identified by Giese and Cote (2000)

in the context of this dissertation.

2.3.1 Customer (dis)satísfaction as a response

Customer (dis)satisfaction has been typically conceptualized following four

maín theoretical approaches: cognitive, affective, contingent, and cognitiveaffective. The cognitive approach is based on the popular view that the

confirmation/disconfirmation of preconsumption product standards is the

essential determinant of (dis)satisfaction (e.g., Bloemer and Kasper, 1995;

Churchill and Surprenant, 1982; Halstead et al., 1994; Tse and Wilton, 1988).

This paradigm posits that confirmed standards lead to modérate satisfaction,

positively disconfirmed (exceeded) standards lead to high satisfaction, and

negatively disconfirmed (underachieved) standards lead to dissatisfaction.

The affective approach views satisfaction as an affective response (e.g.,

Babin and Griffin, 1998; Cadotte et al., 1987; Westbrook, 1980; Woodruff et

al., 1983). Consumer satisfaction, therefore, can be described as an emotion

resulting from appraisals (including positive disconfirmation, perceived

6

Following Bitner and Hubbert (1994), we define service encounter satisfaction as "the

consumer's (dis)satisfaction with a discrete service encounter (p. 76)", and overall service

satisfaction as "the consumer's overall (dis)satisfaction with the organization based on all

encounters and experiences with that particular organization (p. 77)".

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Service failures: theoretical considerations • 33

performance, etc.) of a set of experiences (Westbrook, 1980; Woodruff et al.,

1983).

The contingent approach, based on the work of Fournier and Mick (1999),

views satisfaction as a context-dependent process consisting of a multi-model,

multi-modal blend of motivations, cognitions, emotions, and meanings,

embedded in socio-cultural settings, that transforms during progressive and

regressive consumer-product interactions (a dynamic process).

Finally, more recent (dis)satisfaction definitions concede that

(dis)satisfaction has a dual origin, that is, cognitive and affective (e.g., Mano

and Oliver, 1993; Oliver, 1989, 1993, 1997; Westbrook, 1987; Westbrook and

Oliver, 1991; Wirtz and Bateson, 1999; Yi, 1990). Thus, (dis)satisfaction is not

a solely cognitive phenomenon, rather, is likely to comprise an element of affect

or feelings (Yi, 1990, p. 34). This is the approach followed in the first two

studies (Chapters 4 and 5) of this dissertation, which account explicitly for the

specifíc negative emotion of anger and for the customer's (dis)satisfaction

response. In the third study (Chapter 6), we do not investígate explicitly these

variables.

2.3.2 The focus of the customer (dis)satisfaction response

The focus of the (dis)satisfaction response identifies the object of a

consumer's (dis)satisfaction and usually entails comparing performance to some

standard (Giese and Cote, 2000). Several comparison standards, from very

specifíc to more general, have been used in past research, which can be

summarized as follows (Yi, 1990): (1) expectation-disconfirmation paradigm

(e.g., Oliver, 1980, 1981, 1997); (2) comparison level theory (e.g., Swan and

Martin, 1980); (3) equity theory (e.g., Fisk and Young, 1985); (4) norms as

comparison standards (e.g., Woodruff et al., 1983); and (5) value-percept

disparity theory (e.g., Westbrook and Reilly, 1983).

There are often múltiple foci to which these various standards are directed

including the product (e.g., Tse and Wilton, 1988), the consumption experience

(e.g., Bearden and Teel, 1983), a salesperson (e.g., Oliver and Swan, 1989), or a

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

34 • Chapter 2

store/acquisition (e.g., Oliver, 1981), among others. This variety of foci is

confirmed in the work of Giese and Cote (2000).

In this dissertatíon, the focus of the (dis)satisfaction response will be the

service failure experienced. In the fírst study (Chapter 4), the focus (i.e., service

failure) will be a flight delay. In the next two studies (Chapters 5 and 6), the

focus (i.e., service failure) will be the bank's response (or lack of response) to

the problem experienced by the customer.

2.3.3 The timing of the customer (dis)satisfaction response

Following Giese and Cote (2000), (dis)satisfaction can be determined at

various points in time, although it is generally accepted that it is a post-purchase

phenomenon (Yi, 1990; e.g., Churchill and Surprenant, 1982; Fornell, 1992;

Oliver, 1981; Tse and Wilton, 1988; Westbrook and Oliver, 1991).

Additionally, Cote et al. (1989) argüe that satisfaction can vary dramatically

over time and that it is only determined at the time the evaluation occurs.

Therefore, Giese and Cote (2000) suggest that researchers should select the

point of determination most relevant for the research questions.

We consider that customer (dis)satisfaction is determined after service

failure occurs, which in the specific context of this dissertation means after a

flight delay in the fírst study (Chapter 4) and after a failed recovery in the other

two studies (Chapters 5 and 6)7.

In the following section, we review the specific factors present in the two

studies carried out in this dissertation which explicitly investigate/examine in

their proposed models customer (dis)satisfaction in service failure encounters

(Chapters 4 and 5). We will just review the influence of those factors on

customer (dis)satisfaction with service failures, letting their specific

contextualization to the corresponding chapter.

7

We recognize that, since services are a process, the service is also evaluated during the process

of service delivery. Henee, (dis)satisfaction may also oceur during that whole process and not

only at the end. However, our measures of customer (dis)satisfaction have been developed,

adopting the proposals of Giese and Cote (2000), focusing on the specific moment at which the

service failure takes place.

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Service failures: theoretical considerations • 35

2.4 Antecedents/Determinants of customer (dis)satisfaction in service

failure encounters

Since the early 1970s, one of the major developments in customer

(dis)satisfaction research has been a focus on the theoretical determinants of

(dis)satisfaction. A fairly consistent pattern emerged in that most models were

variations of Oliver's (1980) expectancy-disconfírmation model. Oliver's

(1980) model proposes that customer satisfaction is a positive function of

customer expectations (i.e., pre-purchase customer beliefs about anticipated

product performance) and disconfirmation beliefs (i.e., post-purchase customer

beliefs about the extent to which product performance met expectations).

Later modifications to the expectancy-disconfírmation model of satisfaction

were primarily in the form of adding new predictors in an attempt to provide

greater explanatory power. These variables included, among others, alternative

comparison standards, product performance, causal attributions, affective

response, and equity (see Oliver and DeSarbo, 1988; Oliver and Swan, 1989;

Tse and Wilton, 1988; Westbrook, 1987; Zeithaml et al, 1993).

Specifícally, research on consumer (dis)satisfaction and complaining

behavior has identified individual and contextual characteristics associated with

active responses to dissatisfaction (see Fornell and Wernefelt, 1987; Singh,

1990). Higher income and education (Warland et al., 1975), professional

occupational status (Andreasen, 1985), younger age (Morganosky and Buckley,

1986),

self-confidence

(Gronhaug

and

Zaltman,

1981),

assertiveness/aggressiveness (Richins, 1983), and knowledge and experience

with the service firm (Singh, 1990) are among the individual characteristics

associated with dissatisfaction responses (Dubé and Maute, 1996). Product,

market and contextual variables such as problem severity, blame attributions,

amount of effort to complain (Richins, 1983), expected complaining

consequences (Singh, 1990) and redress environment characteristics (Bolfing,

1989) have also been shown to influence behavioral responses to dissatisfaction.

Other variables that have been analyzed regarding their effect on customer

(dis)satisfaction are performance/expectation ambiguity (Nyer, 1996), product

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

36 • Chapter 2

involvement or importance (Oliver and Bearden, 1981), or consumption valúes

(Oliver, 1996).

However, in this section we will only examine the different predictors of

customer (dis)satisfaction that have been employed in the different empirical

applications present in this dissertation. Specifically, we will address the

following antecedents: service features (failure magnitude and perceived

waiting time), causal attributions, customer emotions, and perceived justice.

2.4.1 Service features

Customer (dis)satisfaction with a service is influenced signifícantly by the

customer's evaluation of service features. For a service such as an airline, an

important feature would be punctuality (Taylor, 1994). For a service such as a

retail bank, important features might include the (competitive) interest rates

(Laroche and Taylor, 1988), or the (convenient) bank location (Levesque and

McDougall, 1996). In any case, research has shown that customers will make

trade-offs among different service features depending, among other issues, on

the criticality of the service (Ostrom and Iacobucci, 1995).

In this dissertation, the two service features that have been explicitly

examined are the failure magnitude and the perceived waiting time. Regarding

the failure magnitude, Hirschman (1970) was the fírst to assess that consumers

would be more likely to voice their complaints when dissatisfied with an

'important' product. After that, researchers have focused on two major

dimensions of product relevance. The fírst is the traditional notion of

instrumental or utilitarian performance whereby the product is seen as

performing a useful function. The second dimensión is that of hedonic or

aesthetic performance (Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982) whereby producís are

valued for their intrinsically pleasing properties. This two-dimensional approach

is frequently typified as one of thinking versus feeling8.

Another conceptualization of product relevance is that of involvement (Zaichkowsky, 1985)

which reflecte the inherent need fulfillment, valué expression, or interest that consumer has in the

product. Involvement's influence on consumption experiences is best illustrated by the

psychological consequences evoked by a product's heightened relevance to the consumer. These

consequences are known to include higher motivation (Bloch et al., 1986), heightened arousal

Tesis doctoral de la Universidad de Alicante. Tesi doctoral de la Universitat d'Alacant. 2005

Customers' responses to service failures. Empirical studies on private, voice and third-party responses. Ana Belén Casado Díaz.

Service failures: theoretical considerations • 37