Drogas y PCR - Urgencia UC

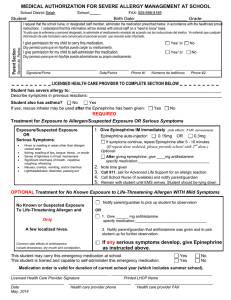

Anuncio

Drogas en PCR Pablo Aguilera F Programa de Medicina de Urgencia P. Universidad Católica de Chile Curso de Reanimación para Residentes Historia y antecedentes • Alta mortalidad • 75% causas cardiovasculares primarias • A pesar de avances la mortalidad es alta • Cifras decepcionantes Continue CPR 30 2 Defibrillation Importance of CPR ACLS DF in <8 min Bystander CPR Early access 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Odds Ratio Stiell (2005) N Engl J Med Presión perfusión Coronary Perfusion Pressure (CPP) Key to coronaria Successful Resuscitation Presión de perfusión coronaria= PPC Aod CPP = Aod - RAd PPC=PAod- PAud RAd ¿Para que sirven las drogas? • Tener en cuenta que PCR = Flujo CERO • NO SIRVEN DE MUCHO EN RELACION A EVIDENCIA DURA Three-Phase Model of Resuscitation Weisfeldt ML, Becker LB. JAMA 2002: 288:3035-8 100% Myocardial ATP 0 Circulatory Phase Electrical Phase 0 2 4 6 8 Metabolic Phase 10 12 Arrest Time (min) 14 16 18 20 OPALS • • • • • Ontario Prehospital Advanced Life Support trial Programa de desfibrilación rápida + ACLS 5638 pacientes Conclusión: La suma de ACLS (drogas cardioactivas) a programa de desfibrilación, aumenta ROSC y admisión al hospital. No mejora sobrevida al alta. Algoritmo ACLS AHA 2010 Neumar R W et al. Circulation 2010;122:S729-S767 Copyright © American Heart Association Algoritmo circular ACLS AHA 2010 Neumar R W et al. Circulation 2010;122:S729-S767 Copyright © American Heart Association Drogas utilizadas en RCP • Vasopresores • Antiarrítmicos • Buffers • Otras: Estrógenos, nitroprusiato Alternativas de Administración • Oro- traqueal • Endovenosa • Intraósea Importancia de “llenar la bomba” Importance of “Priming the Pump” Importance of Priming the Pump Importance “Priming the Pump Importance of the Pump Importance of ““Priming the Pump ” ”””” Importance of “Priming Priming the Pump Importance of “Priming the Pump” Myocardial Cell Myocardial Cell Myocardial Myocardial Cell Myocardial Cell Myocardial Cell Myocardial CellCell 100% ATP 100% ATP 100% ATP 100% ATP 100% ATP 100% 100% ATPATP Myocardial Myocardial Cell Myocardial Cell Myocardial Cell Myocardial Cell Myocardial Cell Myocardial CellATPCell <10% <10% ATP <10% ATP <10% ATP ATP <10% ATP <10% ATP Myocardial Cell Myocardial Myocardial CellCell Myocardial Cell Myocardial Cell Myocardial Cell Myocardial 30-40% ATP 30-40% ATP 30-40% ATP 30-40% ATP 30-40% ATP 30-40% ATP Cell 30-40% ATP Perfusión miocárdica: • Δ de perfusión de P°D • Estenosis coronaria Area under the curve (yellow) measurement of “integrated CPP” was 59,223 mm Hg*dt seconds in A (continuous chest compressions) and 35,737 mm Hg*dt seconds in B (interrupted chest compressions). This calculates to a 40% decrease in the integrated area CPP (iCPP) with the interrupted chest compressions. Masaje Torácico Figure 9-2 • Aortic and right atrial pressure tracings demonstrating the coronary perfusion pressure gradient during the relaxation phase of chest compressions. Note the rapid fall off in the diastolic gradient with the cessation of chest compressions, and the time required to “rebuild” a maximal CPP after such interruption. Compresiones torácicas • Interrupciones afectan PPC generada en el ciclo • Las 1° 5-10 CC inician el ΔPPC , óptimo al final de la serie • Al cesar baja a 0 en 5’’ • Al reiniciar se repite el ciclo Drogas utilizadas en RCP • Vasopresores • Antiarrítmicos • Buffers • Otras: Estrógenos, nitroprusiato, corticoides, betabloqueo. 18 Vasopresores • Adrenalina • Vasopresina • Atropina Vasopresores • Evidencia que aumenta la recuperación de pulso. ( ROSC) • No hay trabajos RCT´s que mejore sobrevida o outcome neurológico en este tópico en cualquier ritmo. Adrenalina • Agente simpático-mimético • Efecto α y β • α 1 y α 2: Perfusión • • β 1: • • Vasocontricción arterial --- coronaria Aumenta contractilidad miocárdica. Aumenta el consumo de 02 Emergency Medicine International CPR (indepth, alon, minavoiding se of ther- g delivery, use signifdefibrilla- ental and gs during gs such as e, fibrino- ssue hypn supply- Figure 1: Schematic representation of the action of epinephrine on intracellular calcium in myocytes. ATP: adenosine triphosphate, cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate, Gs: G protein complex, IP: inositol phosphate, PIP2 : phosphoinositol diphosphate, Vasopresores • β 2: • • estimula relajación de musculatura lisa disminuye la presión de perfusión coronaria For reprint orders, please contact: [email protected] University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ, USA Author for correspondence: University of Arizona Sarver Heart Center, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Tel.: +1 520 626 2000 Fax: +1 520 626 0964 [email protected] 1 † The use of epinephrine during cardiac arrest has been advocated for decades and forms an integral part of the published guidelines. Its efficacy is supported by animal data, but human trial evidence is lacking. This is partly attributable to disparities in trial methodology. Epinephrine’s pharmacologic and physiologic effects include an increase in coronary perfusion pressure that is key to successful resuscitation. One possible explanation for the lack of epinephrine’s demonstrated efficacy in human trials of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is the delay in its administration. A potential solution may be intraosseus epinephrine, which can be administered quicker. More importantly, it is the quality of the basic life support, early and uninterrupted chest compressions, early defibrillation and postresuscitation care that will provide the best chance of neurologically intact survival. • Utilizada en pacientes refractarios al SHOCK eléctrico. • Su uso data desde aprox. 100 años • Ventajas y desventajas asociadas a su uso Epinephrine administration has been advocated during resuscitation of cardiac arrest for decades [1–5] . The 2005 guidelines by both the American Heart Association and the European Resuscitation Council recommend its use [6–8] . Surprisingly, definitive evidence for epinephrine’s efficacy in humans is lacking. As with many components of the Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiac Care, its recommendation is largely based on tradition and its success in animal models. Conflicting results between animal and human research are due to the disparate methodology and populations studied, as well as the duration of untreated and treated cardiac arrest prior to epinephrine administration. The purpose of this article is As early as 1906, Crile and Dolley noted the importance of an adequate aortic diastolic pressure during attempted cardiac resuscitation [11] . They stated that it often was not possible to achieve an adequate aortic diastolic pressure without the addition of epinephrine. Since epinephrine has both inotropic and chronotropic effects on the beating heart and also produces peripheral vasoconstriction, there was confusion regarding which of these effects was the most important. Epinephrine increases the peripheral vascular resistance, transiently decreasing perfusion to most of the body, but in the process increases the aortic diastolic pressure and perfusion to the heart. The classic studies of Pearson and Redding performed in the 1960s merit emphasis [12–14] . Review Robert R Attaran1 & Gordon A Ewy† Future Cardiology Epinephrine in resuscitation: curse or cure? Altas dosis de Adrenalina R E P E AT E D H I G H D O S E S A N D STA N DA R D D O S E S O F E P I N E P H R I N E F O R C A R D I AC A R R E ST O U T S I D E T H E H O S P I TA L A COMPARISON OF REPEATED HIGH DOSES AND REPEATED STANDARD DOSES OF EPINEPHRINE FOR CARDIAC ARREST OUTSIDE THE HOSPITAL PIERRE-YVES GUEUGNIAUD, M.D., PH.D., PIERRE MOLS, M.D., PH.D., PATRICK GOLDSTEIN, M.D., EMMANUEL PHAM, M.D., PIERRE-YVES DUBIEN, M.D., CARINE DEWEERDT, PH.D., MICHEL VERGNION, M.D., PAUL PETIT, M.D., AND PIERRE CARLI, M.D., FOR THE EUROPEAN EPINEPHRINE STUDY GROUP* ABSTRACT Background Clinical trials have not shown a benefit of high doses of epinephrine in the management of cardiac arrest. We conducted a prospective, multicenter, randomized study comparing repeated high doses of epinephrine with repeated standard doses in cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Methods Adult patients who had cardiac arrest outside the hospital were enrolled if the cardiac rhythm continued to be ventricular fibrillation despite the administration of external electrical shocks, or if they had asystole or pulseless electrical activity at the time epinephrine was administered. We randomly assigned 3327 patients to receive up to 15 high doses (5 mg each) or standard doses (1 mg each) of epinephrine according to the current protocol for advanced cardiac life support. Results In the high-dose group, 40.4 percent of 1677 patients had a return of spontaneous circulation, as compared with 36.4 percent of 1650 patients in the standard-dose group (P=0.02); 26.5 percent of the patients in the high-dose group and 23.6 percent of those in the standard-dose group survived to be admitted to the hospital (P=0.05); 2.3 percent of the patients in the high-dose group and 2.8 percent in the standard-dose group survived to be discharged from the hospital (P=0.34). There was no significant difference in neurologic status according to treatment among those discharged. High-dose epinephrine improved the rate of successful resuscitation in patients with asystole, but not in those with ventricular fibrillation. Conclusions In our study, long-term survival after cardiac arrest outside the hospital was no better with repeated high doses of epinephrine than with repeated standard doses. (N Engl J Med 1998;339:1595-601.) To pursue this question further, we conducted a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study to compare the efficacy of repeated 1-mg doses of epinephrine with that of repeated 5-mg doses of epinephrine in adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. METHODS The French and Belgian Emergency Medical Systems Cardiac arrest occurring outside the hospital in France and Belgium is managed by the Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente.14,15 Each medical region has a dispatching center located in a major hospital that controls several units, called Services Mobiles d’Urgence et de Réanimation, that are based in other hospitals within the region. Each hospital is equipped with several ambulances that carry a physician, a nurse, and a trained driver. The telephone number is a national emergency number. Switchboard operators, available 24 hours a day, receive all calls related to cardiac arrest in the dispatching centers and forward them to the dispatching physician, who decides whether to send out a team of emergency medical technicians (who are members of the fire-department rescue services) and, at the same time, an ambulance staffed by the medical team. Because of the greater numbers of emergency medical technicians, they are frequently closer to the patient and can start basic life support before the arrival of the medical team. The medical units provide advanced cardiac life support, according to the American Heart Association guidelines adapted for Europe by the European Resuscitation Council, until a return of spontaneous circulation is observed on the scene or a decision is made by the team physician to stop cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Mayor ROSC y admisión hospitalaria. Sin diferencias en mortalidad ni outcome neurológico Study Design The study was approved by the ethics committees of the university hospitals in Lyons and Brussels and by the Consultative Council for the Protection of Persons Volunteering for Biomedical Research of our institution; approval was valid for each of the participating study centers. Waiver of informed consent was accepted by the council because of the urgency of the situation of the subjects with cardiac arrest and the lack of availability of family members. ©1998, Massachusetts Medical Society. E PINEPHRINE remains the first-line adrenergic agent used for cardiac arrest, but the dose remains controversial.1-3 Almost all experimental studies suggest that high-dose epinephrine is more effective than the currently recommended doses; higher doses increase myocardial and cerebral blood flow and improve rates of survival in animals.4-9 In contrast, with the exception of a recent multinational study,10 multicenter clinical trials have From the Department of Anesthesiology and Emergency Medical System, Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente of Lyons, Edouard Herriot Hospital, Claude Bernard University, Lyons, France (P.-Y.G., P.-Y.D., P.P.); the Department of Emergency Medicine and Emergency Medical System, Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente of Brussels, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Saint-Pierre, Brussels, Belgium (P.M.); the Department of Anesthesiology and Emergency Medical System, Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente of Lille, Centre Hospitalier Régional et Universitaire of Lille, Lille, France (P.G.); the Department of Computers and Statistics, Medical Service, Claude Bernard University, Lyons, France (E.P.); the Pharmaceutical Department, Edouard Herriot Hospital, Lyons, France (C.D.); the Department of Emergency Medicine, Service Mobile d’Urgence et de Réanimation of the Centre Hospitalier Régional Citadelle, Liege, Belgium (M.V.); and the De- mittees, Crown Law and Guardianship Boards, the concerns of our findings. However we considered this trial needed to be pragbeing involved in a trial in which the unproven “standard of care” matic in having few exclusion criteria, recognising that the timing was being withheld prevented four of the five ambulance services of drug administration will vary depending on the successful estabfrom participating. In addition adverse press reports questionlishment of intravenous access and variations in the resuscitation ing the ethics of conducting this trial, which subsequently led to processes of care including CPR quality. This, in essence reflects the involvement of politicians, further heightened these concerns. current clinical practice. As blinding was well preserved in this Despite the clearly demonstrated existence of clinical equipoise for study we consider the likelihood of these factors being differentially Resuscitation 1138–1143 adrenaline in cardiac arrest it remained impossible to change distributed the 82 (2011) between the two study arms to be small. decision not to participate. As a single centre study with approxiFinally, participation in the study by the SJA-WA paramedics Contents lists is availablewas at ScienceDirect mately 500 out of hospital cardiac arrests in which resuscitation voluntary, hence only 40% of eligible patients were recruited. commenced per year, it would not have been possible to reach the We are unable to exclude the potential for selection bias, however Resuscitation required sample size. In addition it was not possible to continue as trial patients were well matched on baseline characteristics and the study drugs reached their expiry date and no additional fundthere is no reason to suggest that paramedics who participated in j o uadequate r n a l h o m e sample p a g e : w wsize w . e l s e v i ethe r . c otrial m / l owere c a t e / rmore e s u s c ilikely t a t i o n to selectively enroll patients into the trial. ing was available. The failure to achieve an left the trial underpowered to detect significant effects on survival This study is unique in that it is the first randomised double blind to hospital discharge. placebo-controlled trial of adrenaline in cardiac arrest. To date the Clinical paper Second we were unable to assess the influence of CPR quality evidence base underpinning this “standard of care” intervention Effect ofadministration adrenaline on survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: randomised or the timing of adrenaline during resuscitation on has been restricted to animalAand non-randomised clinical studies Adrenalina A randomised mpson double-blind placebo-controlled trial! Ian G. Jacobs a,c,∗ , Judith C. Finn a,c , George A. Jelinek b , Harry F. Oxer c , Peter L. Thompson d,e Table 2 of Emergency University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, 6009 Western Australia, Australia receiving placeboMedicine versus(M516), adrenaline. Outcomes for patientsa Discipline b d,e enaline (epinephrine) in treating ndard of care for many decades. nt survival to hospital discharge d trial of adrenaline in out-ofine 1:1000 or placebo (sodium ve 1 ml aliquots of the trial drug ed included survival to hospital ulation (ROSC) and neurological period of which 601 underwent s: 262 in the placebo group and acteristics including age, gender ving placebo and 64 (23.5%) who arge occurred in 5 (1.9%) and 11 % CI 0.7–6.3). All but two patients tatistically significant improveere was a significantly improved Outcome Department of Medicine, University of Melbourne (St Vincents Hospital), Victoria Parade, Fitzroy, 3065 Melbourne, Australia St John Ambulance (Western Australia), PO Box 183, Belmont 6984, Western Australia, Australia Placebo (n = 262), n (%) Adrenaline (n = 272), n School of Medicine and Population Health, University of Western Australia, Western Australia, Australia e Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Hospital Avenue, Nedlands, 6009 Western Australia, Australia c d ROSC achieved pre-hospital Admitted to hospital Survived to hospital discharge a r t i c l e CPC 1 or 2 i n f o 22 (8.4%) 34 (13.0%) 5 (1.9%) 5 (100%) a b s t r a c t 64 (23.5%) 69 (25.4%) 11 (4.0%) 9 (81.8%) (%) OR (95% CI) p-Value 3.4 (2.0–5.6) 2.3 (1.4–3.6) 2.2 (0.7–6.3) n/a <0.001 <0.001 0.15 0.31 Article history: Received 19 June 2011 Received in revised form 22 June 2011 Accepted 24 June 2011 Background: There is little evidence from clinical trials that the use of adrenaline (epinephrine) in treating cardiac arrest improves survival, despite adrenaline being considered standard of care for many decades. Table 3 The aim of our study was to determine the effect of adrenaline on patient survival to hospital discharge in out of hospital cardiac arrest. non-shockable initial cardiac arrest rhythm. Patient outcomes for adrenaline versus placebo by shockable and Methods: We conducted a double blind randomised placebo-controlled trial of adrenaline in out-ofadrenaline 1:1000 or placebo (sodium Shockable (n = 245)hospital cardiac arrest. Identical study vials containing either Non-shockable (n = 289) Keywords: chloride 0.9%) were prepared. Patients were randomly allocated to receive 1 ml aliquots of the trial drug Adrenaline according to current advanced support assessed includedAdrenaline survival to hospital Adrenaline ORlife (95% CI) guidelines. Outcomes Placebo Out of hospital cardiac arrest Placebo discharge (primary outcome), pre-hospital return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and neurological p-Value Randomised controlled trial outcome (Cerebral Performance Category Score – CPC). Survival Results: A total of 4103 cardiac were screened during the study period of which32 601 underwent Ambulance 5 (3.7%) ROSC achieved pre-hospital 17 (13.5%) 32 (26.9%) 2.4arrests (1.2–4.5) (20.9%) randomisation. Documentation was available for a total of 534 patients: 262 in the placebo group and p = 0.009 272 in the adrenaline group. Groups were well matched for baseline characteristics including age, gender 15 (11%) 19 (15.1%) 33 (27.7%) 2.2 (1.2–4.1) 36 (23.5%) Admitted to hospital and receiving bystander CPR. ROSC occurred in 22 (8.4%) of patients receiving placebo and 64 (23.5%) who p = 0.01 received adrenaline (OR = 3.4; 95% CI 2.0–5.6). Survival to hospital discharge occurred in 5 (1.9%) and 11 5 (4.0%) 9 (7.6%) 2.0 (0.6–6.0) (0%) 2 (1.3%) Survived to hospital discharge (4.0%) patients receiving placebo or adrenaline respectively0 (OR = 2.2; 95% CI 0.7–6.3). All but two patients 0.23 p =had (both in the adrenaline group) a CPC score of 1–2. Conclusion: Patients receiving adrenaline during cardiac arrest had no statistically significant improvement in the primary outcome of survival to hospital discharge although there was a significantly improved likelihood of achieving ROSC. © 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Cardiac arrest occurring out of hospital is a significant public health issue with an estimated incidence in the United States of 95.7 per 100,000 person years.1,2 The overall case fatality varies across different emergency medical services, but is mostly in excess of 90% and has improved little over the last three decades.2 The routine use of adrenaline (epinephrine) in treating cardiac arrest has been recommended for over half a century, being first ! A Spanish translated version of the abstract of this article appears as Appendix in the final online version at doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.06.029. ∗ Corresponding author at: Discipline of Emergency Medicine (M516), University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Hwy, Crawley, 6009 Western Australia, Australia. Tel.: +61 418 916 261. E-mail address: [email protected] (I.G. Jacobs). 0300-9572/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.06.029 described in 1906.3 The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) include adrenaline in their advanced life support (ALS) resuscitation guidelines, despite there being no randomised placebo-controlled trials in humans evaluating its efficacy in cardiac arrest.4 In 2010 ILCOR identified the need for randomised clinical trials of vasopressor drugs in the treatment of cardiac arrest.4 Animal studies have shown that adrenaline improves coronary and cerebral perfusion.5 The survival outcomes in human studies (non randomised and observational) have been equivocal.6–9 A meta-analysis of high dose versus standard dose adrenaline did not include a comparison with no adrenaline and showed some benefit of high dose adrenaline on return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) but not survival to hospital discharge.10 In contrast, there has been some concern regarding the potential harmful effects of adrenaline on post cardiac arrest myocardial function and cerebral microcirculation.11,12 OR (95% CI) p-Value 6.9 (2.6–18.4) p < 0.001 2.5 (1.3–4.8) p = 0.005 n/a Cuando usar... • Uso precoz en PCR refractarios al shock • USE la dosis correcta, NO megadosis. • Masaje, masaje, ELECTRICIDAD Vasopresina • Secretada por la neuro-hipófisis • Actúa en receptores V 1 endotelial produciendo vasocontricción. • No tiene efecto sobre miocardiocito. journal of medicine january 8 , 2004 established in 1812 vol. 350 no. 2 A Comparison of Vasopressin and Epinephrine for Out-of-Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Volker Wenzel, M.D., Anette C. Krismer, M.D., H. Richard Arntz, M.D., Helmut Sitter, Ph.D., Karl H. Stadlbauer, M.D., and Karl H. Lindner, M.D., for the European Resuscitation Council Vasopressor during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Study Group* The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e abstract original article background Vasopressin is an alternative to epinephrine for vasopressor therapy during cardiopul- From the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Leopold-Franmonary resuscitation, but clinical experience withEpinephrine this treatment has been limited. Vasopressin and vs. Epinephrine zens University, Innsbruck, Austria (V.W., methods K.H.S., K.H.L.); the Department of Alone in Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationA.C.K., Medicine, Division of Cardiology–Pulmonol- We randomly assigned adults who had had an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest toM.D., receive Pierre-Yves Gueugniaud, M.D., Ph.D., Jean-Stéphane David, Ph.D.,ogy, Benjamin Franklin Medical Center, Free Ericvasopressin Chanzy, M.D.,orHervé Ph.D., Pierre-Yves Dubien, M.D., University, Berlin, Germany (H.R.A.); and two injections of either 40 IU of 1 mgHubert, of epinephrine, followed by addithe Institute for Theoretical Surgery, PhilPatrick Mauriaucourt, Bragança, M.D.,was Xavier Billères,to M.D., tional treatment with epinephrine if needed.M.D., The Coralie primary end point survival ipps University, Marburg, Germany (H.S.). Marie-Paule Clotteau-Lambert, M.D., Patrick Fuster, M.D., Didier Thiercelin, M.D., hospital admission, and theGuillaume secondary end point was survival to hospital discharge. Debaty, M.D., Agnès Ricard-Hibon, M.D., Patrick Roux, M.D.,Address reprint requests to Dr. Lindner at the Department of Anesthesiology and CritCatherine Espesson, M.D., Emgan Querellou, M.D., Laurent Ducros, M.D., Patrick Ecollan, M.D., Laurent Halbout, M.D., Dominique Savary, M.D.,ical Care Medicine, Leopold-Franzens University, Anichstr. 35, 6020 Innsbruck, AusA total of 1219 patients underwent randomization; 33 were excluded miss-M.D., Frédéric Guillaumée, M.D., Régine Maupoint, M.D.,because Philippe of Capelle, tria, or at [email protected]. Cécile M.D., Philippe Dreyfus, M.D., Philippe Nouguier, ing study-drug codes. Among the Bracq, remaining 1186 patients, 589 were assigned to M.D., reAntoine Gache, M.D., Claude Meurisse, M.D., Bertrand Boulanger, M.D., *The investigators who participated in the ceive vasopressin and 597 to receive epinephrine. The two treatment groups had simiClaude Lae, M.D., Jacques Metzger, M.D., Valérie Raphael, M.D., study group are listed in the Appendix. lar clinical profiles. There Arielle were Beruben, no significant differences in the rates of hospital M.D., Volker Wenzel, M.D., Comlavi Guinhouya, Ph.D., admission between the vasopressinChristian group and the epinephrine group either among Vilhelm, Ph.D., and Emmanuel Marret, M.D. pa- N Engl J Med 2004;350:105-13. results From Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente 2004 Massachusetts tients with ventricular fibrillation (46.2 percent vs. 43.0 percent, P=0.48) or among Copyright ©(SAMU) 69, HospicesMedical Civils deSociety. Lyon, UniA BS T R AC T versity of Lyon 1, Lyon (P.-Y.G., J.-S.D.); those with pulseless electrical activity (33.7 percent vs. 30.5 percent, P=0.65). Among SAMU 93, Bobigny (E.C.); Health Engineering Institute, University of Lille, Lille (H.H., patients with asystole,BACKGROUND however, vasopressin use was associated with significantly C.G., C.V.); Service Mobile d’Urgence et the administration of advanced life in support for resuscitation from de Réanimation (SMUR), Edouard Herriot higher rates of hospitalDuring admission (29.0 percent, vs. 20.3cardiac percent the epinephrine cardiac discharge arrest, a combination of vasopressin and epinephrine may Among be more effective Hospital, Lyon (P.-Y.D.); SAMU 59, Lille group; P=0.02) and hospital (4.7 percent vs. 1.5 percent, P=0.04). than epinephrine or vasopressin alone, but evidence is insufficient to make clinical (P.M.); SAMU 33, Bordeaux (C. Bragança); 732 patients in whom spontaneous circulation was not restored with the two injections Bataillon des Marins Pompiers, Marseille recommendations. (X.B.); SAMU 44, Nantes (M.-P.C.-L.); of the study drug, additional SMUR, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire METHODStreatment with epinephrine resulted in significant imLyon-Sud, Lyon (P.F.); SAMU 06, provement in the rates of to hospital admission and hospital discharge in the In asurvival multicenter study, we randomly assigned adults with out-of-hospital cardiac ar- (CHU) Nice (D.T.); SAMU 38, Grenoble (G.D.); receive injections of either 1 mg admission of epinephrinerate, and 40 IU of vaso- SMUR, Beaujon Hospital, Beaujon vasopressin group, butrest nottoin the successive epinephrine group (hospital 25.7 SAMU 31, Toulouse (P.R.); pressin or 1 mg of epinephrine and saline placebo, followed by administration percent vs. 16.4 percent; P=0.002; hospital discharge rate, 6.2 percent vs. 1.7 percent; of the (A.R.-H.); 42, Saint-Etienne (C.E.); SAMU 29, same combination of study drugs if spontaneous circulation was not restored and sub- SAMU Brest (E.Q.); SMUR, CHU Lariboisière, Paris P=0.002). Cerebral performance was similar in the two groups. sequently by additional epinephrine if needed. The primary end point was survival conclusions to hospital admission; the secondary end points were return of spontaneous circulation, survival to hospital discharge, good neurologic recovery, and 1-year survival. (L.D.); SMUR, CHU Pitié–Salpêtrière, Paris (P.E.); SAMU 14, Caen (L.H.); SAMU 74, Annecy (D.S.); SMUR, Croix-Rousse Hos- Vasopressin vs. Epinephrine in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Vasopresina v/s adrenalina PCR- EH Wenzel V et al. NEJM 2004; 350:105-13 1,186 patients Vasopressin 40 units vs. epinephrine 1 mg IV q 3 min x 2 doses If no ROSC, an additional 1 mg dose of epinephrine given at MD discretion • • Epinephrine (n= 597) Vasopressin (n= 598) 1186 pacientes Vasop 40 ui vs 1 mg adrenalina cada 3 min x 2 dosis 25% % Discharged ns 19% 20% 15% 18% ns 10% 10% 9% 10% ns 6% 5% 0% p= .04 5% 2% Overall VF PEA Asystole Vasopressin vs. Epinephrine in OutOut-ofof-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Wenzel V et al. NEJM 2004; 350:105350:105-13 1,186 patients Vasopressin 40 units vs. epinephrine 1 mg IV q 3 min x 2 doses If no ROSC, an additional 1 mg dose of epinephrine given at MD discretion Epinephrine (n= 597) Vasopressin (n= 598) Epinephrine vs. vasopressin for in-hospital cardiac arrest Adrenalina v/s vasopresina PCR IH Stiell IG et al. Lancet 2001; 358:105-9 • • 200 patients in cardiac arrest requiring drug 200therapy pacientes en PCREpi 1 mg vs. vasopressin 40 Epi units 1 mgIVvs vasopresina 40 ui IV Epinephrine Vasopressin 75% 50% ns 35% 39% ns 25% 14% 12% 0% 1-hr survival Discharged Epinephrine vs. vasopressin for in-hospital cardiac arrest Stiell IG et al. Lancet 2001; 358:105358:105-9 200 patients in cardiac arrest requiring drug therapy Epi 1 mg vs. Epinephrine 75% 50% ns 39% Vasopressin Atropina • • • • • Trabajos de años 80 Revierte disminuciones FC, RVS y PA colinérgicas. Util en bradicardia sinusal . Se pensó de su utilidad en AESP y asistolía en base a algunos reportes de casos 3 mg resulta en bloqueo vagal completo. Atropina • • • Aumenta demanda miocárdica de oxígeno y puede iniciar taquiarritmias. Dosis < 0,5 mg pueden ser parasimpaticomiméticas. Uso cuidadoso en SCA ó IAM. Advance Publication by J-STAGE Circulation Journal Official Journal of the Japanese Circulation Society http://www.j-circ.or.jp Atropine Sulfate for Patients With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest due to Asystole and Pulseless Electrical Activity The Survey of Survivors After Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest in KANTO Area, Japan (SOS-KANTO) Study Group Background: The 2005 guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) have recommended that administration of atropine can be considered for non-shockable rhythm, but there are insufficient data in humans. • • No debe ser utilizada de manera rutinaria No mejora outcome neurológico Methods and Results: The effects of atropine were assessed in 7,448 adults with non-shockable rhythm from the SOS-KANTO study. The primary endpoint was a 30-day favorable neurological outcome after cardiac arrest. In the 6,419 adults with asystole, the epinephrine with atropine group (n=1,378) had a significantly higher return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) rate than the epinephrine alone group (n=5,048) with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.6 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.4–1.7, P<0.0001), but the 2 groups had similar 30-day favorable neurological outcome with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.6 (95%CI 0.2–1.7; P=0.37). In the 1,029 adults with pulseless electrical activity (PEA), the 2 groups had similar rates of ROSC and 30-day favorable neurological outcome, and the epinephrine with atropine group had a significantly lower 30-day survival rate than the epinephrine alone group with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.4 (95%CI 0.2–0.9, P=0.016). en pacientes con PCR con ritmo no desfibrilable. Conclusions: Administration of atropine had no long-term neurological benefit in adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to non-shockable rhythm. Atropine is not useful for adults with PEA. • EN SUMA: ACLS 2010 no lo considera Key Words: Asystole; Atropine; Cardiac arrest; Neurological outcome; Pulseless electrical activity (PEA) como parte de su algoritmo C ardiac arrest is a major public health problem in the world. Recent guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care have shown that basic CPR and early defibrillation are of primary importance, and drug administration for advanced cardiac life support (ALS) is of secondary importance during cardiac arrest.1–3 There have been recent 2 clinical studies on ALS in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. A multicenter, controlled clinical study by Stiel et al demonstrated that standard ALS, which includes endotracheal intubation and/or intravenous drug administration, does not improve 4 survival in humans. However, the use of atropine improves short-term survival and is inexpensive and easy to administer.1 Literature to refute the use of atropine for asystole and PEA is equally sparse and of limited quality.1 Asystole can be precipitated or exacerbated by excessive vagal tone, and administration of a vagolytic medication is consistent with a physiologic approach.6 Moreover, recent CPR guidelines have reported that administration of atropine remains a first line drug for acute symptomatic bradycardia (Class 2a; weight of evidence is in favorer of usefulness/efficacy). On the basis of these findings, administration of atropine can be considered Drogas utilizadas en RCP • Vasopresores • Antiarrítmicos • Buffers • Otras: Estrógenos, nitroprusiato, corticoides. 35 Antiarrítmicos • Muchos efectos • bloqueo canales de sodio • bloqueo canales de potasio • bloqueo canales de calcio Principios Básicos • Antiarrítmicos no mejoran sobrevida en PCR. • Considerar efectos arritmogénicos. • • Interacciones entre AA Evitar asociaciones de AA. • Ojo con corazones enfermos. • ICC mayor riesgo arritmogénico Potencial de acción... 0 – Canales de Na++ 1 – Salida K+ 2 – Entrada Ca++ 3 – Cierre canales Ca++ + Salida K+ Clasificación Vaughan Williams • Se basa en los canales iónicos bloqueados: • Na+, K+ ó Ca++ • Efecto Beta bloqueador • Efecto en la conducción y repolarización Amiodarona • Droga compleja con efectos en los canales de Na+, K+ y Ca++,asi como propiedades de bloqueo alfa y beta adrenórgico. • Útil en arritmias auriculares y Ventriculares. • Eficaz y con poco efecto arritmogénico • Dilata las arterias coronarias y aumenta el flujo coronario Amiodarona • Lo malo... Hipotensión y bradicardia • Principalmente por vehículo y liberación de histamina. AMIODARONE FOR RESUSCITATION AF TER OUT- OF-HOSPITAL CARDIAC ARREST AMIODARONE FOR RESUSCITATION AFTER OUT-OF-HOSPITAL CARDIAC ARREST DUE TO VENTRICULAR FIBRILLATION PETER J. KUDENCHUK, M.D., LEONARD A. COBB, M.D., MICHAEL K. COPASS, M.D., RICHARD O. CUMMINS, M.D., ALIDENE M. DOHERTY, B.S.N., C.C.R.N., CAROL E. FAHRENBRUCH, M.S.P.H., ALFRED P. HALLSTROM, PH.D., WILLIAM A. MURRAY, M.D., MICHELE OLSUFKA, B.S.N., AND THOMAS WALSH, M.I.C.P. S ARREST Trial UDDEN death from cardiac causes, often due to ventricular fibrillation, claims at least Background Whether antiarrhythmic drugs im250,000 persons annually in the United prove the rate of successful resuscitation after outStates.1,2 The American Heart Association of-hospital cardiac arrest has not been determined in randomized clinical trials. guidelines for advanced cardiac life support state that Methods We conducted a randomized, doubleantiarrhythmic medications are “acceptable, probably blind, placebo-controlled study of intravenous amiohelpful” for the treatment of ventricular fibrillation darone in patients withKudenchuk out-of-hospital P cardiac or pulseless tachycardia et al.ar-N Engl J Medventricular 1999; 341:871 -8that persists after rest. Patients who had cardiac arrest with ventricular three or more shocks from an external defibrillator fibrillation (or pulseless ventricular tachycardia) and (often called “shock-refractory” ventricular fibrillawho had not been resuscitated after receiving three tion or tachycardia).3 This guarded recommendation or more precordial shocks were randomly assigned reflects the limited evidence supporting the use of to receive 300 mg of intravenous amiodarone (246 Persistent or patients) or placebo (258 patients). • Continue CPRthese agents, none of which have been convincingly demonstrated to improve the IV success attempted VF/VT Results recurrent The treatment groups had similar clinical • Epi 1 mg q 3-5of min • Intubate at once resuscitation after cardiac arrest.4-6 We conducted a profiles. There was no significant difference between • Obtain IV access the amiodarone and placebo groups in the mean randomized clinical trial to determine the efficacy of (±SD) duration of the resuscitation attempt (42±16 300 in mg intravenousAmio amiodarone patients Placebo with out-of-hosand 43±16 minutes, respectively), the number of pital cardiac arrest due to shock-refractory ventricular shocks delivered (4±3 and 6±5), or the proportion fibrillation or tachycardia. of patients who required additional antiarrhythmic • DF 360 J within 30-60 sec ABSTRACT drugs after the administration of the study drug (66 METHODS percent and 73 percent). More patients in the amioThe study was conducted in Seattle and suburban King County, darone group than in the placebo group had hypotenWashington. This region has more than 1.5 million residents and sion (59 percent vs. 48 percent, P=0.04) or bradycardia is served by 21 paramedic base stations and 15 hospitals, all of (41 percent vs. 25 percent, P=0.004) after receiving which participated in the trial. Seattle and King County have sim• IIb medications the study drug. Recipients of amiodarone were more ilar multitiered prehospital emergency-response systems that follow treatment protocols written in• accordance with American Heart likely to survive to be admitted to the hospital Lidocaine Association guidelines for advanced cardiac life support.7 (44 percent, vs. 34 percent of the placebo group; • Bretylium P=0.03). The benefit of amiodarone was consistent • Mg sulfate Protocol • DF 360 30-60 secof after dose among all subgroups andJat all times drugmed admin• Procainamide Victims of cardiac arrest were initially treated by fire-departistration. The adjusted odds ratio for survival to admis• Pattern “drug-shock”, “drug-shock” ment personnel (first responders), whobicarb) initiated basic life-support • (Na sion to the hospital in the amiodarone group as commeasures, including the delivery of shocks by an automated expared with the placebo group was 1.6 (95 percent ternal defibrillator. When paramedics arrived, they provided adconfidence interval, 1.1 to 2.4; P=0.02). The trial did vanced life-support measures. Adults with nontraumatic out-ofnot have sufficient statistical power to detect differhospital cardiac arrest were eligible for inclusion in the study if ences in survival to hospital discharge, which difventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (on inifered only slightly between the two groups. tial presentation or any time in the course of the resuscitation atConclusions In patients with out-of-hospital carditempt) was present after three or more precordial shocks had been ARREST Trial Trial Arrest Kudenchuk P et al. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:871-8 N= 504 70% 60% 50% Survival to 40% Admission 64% p= .03 49% 44% 41% 39% 34% 30% 38% 33% 17% 20% 12% 10% 0% All patients VF Asys or PEA ROSC No ROSC dispatch log sheets, and hospital charts (for admitted patients). • Patients surviving to hospital admission were followed for functional status at discharge as part of the study procedure; however, results are not yet available. Alive Trial Study Protocol Figure 1 Patients with VF = VF persists or recurs 3 Unsuccessful defibrillation attempts IV epinephrine Fourth defibrillation shock RANDOMIZATION IV amiodarone 5 mg/kg AND IV lidocaine placebo IV lidocaine 1.5 mg/kg AND IV amiodarone placebo Fifth defibrillation shock Fifth defibrillation shock Second infusion of amiodarone (2.5 mg/kg) Second infusion of lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg) Further shocks Further shocks Epinephrine infusion at 5-min intervals Epinephrine infusion at 5-min intervals Data from Dorian et al.3 ALIVE Trial Dorian P et al. NEJM; 346:884346:884-90 N= 348 Amio vs. Lido ALIVE Trial Dorian P et al. NEJM; 346:884-90 Alive Trial N= 348 Amio vs. Lido Toronto EMS 911-1st DF = 12 + 7 min 911-drug = 25 + 8 min 25% •n= 345 •Toronto EMS 20% Admission 23% p< .004 15% 10% 11% 5% 0% Amio Lido •Sobrevida a la admisión ALIVE Trial Dorian P et al. NEJM; 346:884346:884-90 N= 348 Amio vs. Lido Toronto EMS 911911-1st DF = 12 + 7 min 911911-drug = 25 + 8 min Ojo con Amiodarona bradicardizantes y vasodilatadores: • Efectos cuidado en ptes inestables. cree que es por efecto de dilución quiza • Se por liberación de histamina. • Nivel de evidencia AHA en PCR: • Grado de recomendación: II B B Procainamide and Survival in Ventricular Fibrillation Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest David T. Markel, Laura S. Gold, MSPH, Judith Allen, MPH, Carol E. Fahrenbruch, MSPH, Thomas D. Rea, MD, MPH, Mickey S. Eisenberg, MD, PhD, and Peter J. Kudenchuk, MD Abstract Objectives: Procainamide is an antiarrhythmic drug of unproven efficacy in cardiac arrest. The association between procainamide and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was investigated to better determine the drug’s potential role in resuscitation. • Estuvo en guidelines 2000 • 2005 fue eliminada por convivencia • Estudio que demostró sobrevida • VWAIa • Efectos vasodilatador • Guidelines actuales avala su uso en FAMethods: The authors conducted a 10-year study of all witnessed, out-of-hospital, ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT) cardiac arrests treated by emergency medical services (EMS) in King County, Washington. Patients were considered eligible for procainamide if they received more than three defibrillation shocks and intravenous (IV) bolus lidocaine. Four logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) describing the relationship between procainamide and survival. Results: Of the 665 eligible patients, 176 received procainamide, and 489 did not. On average, procainamide recipients received more shocks and pharmacologic interventions and had lengthier resuscitations. Adjusted for their clinical and resuscitation characteristics, procainamide recipients had a lower likelihood of survival to hospital discharge (OR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.36 to 0.75). Further adjustment for receipt of other cardiac medications during resuscitation negated this apparent adverse association (OR = 1.02; 95% CI = 0.66 to 1.57). Conclusions: In this observational study of out-of-hospital VF and pulseless VT arrest, procainamide as second-line antiarrhythmic treatment was not associated with survival in models attempting to best account for confounding. The results suggest that procainamide, as administered in this investigation, does not have a large impact on outcome, but cannot eliminate the possibility of a smaller, clinically relevant effect on survival. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 2010; 17:617–623 ª 2010 by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Keywords: antiarrhythmia agents, arrhythmia, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, survival ntiarrhythmic medications are frequently during resuscitation from cardiac arrest, although research supporting their efficacy in this setting is scarce.1–4 Supporting evidence is stronger for their use in the treatment of hemodynamically stable arrhythmias,5 which, along with encouraging results from some animal studies,6 has spurred the extension of their use to From the University of Washington School of Medicine (DTM), Seattle, WA; Division of Emergency Medical Services, Public Health Seattle and King County (DTM, LSG, JA, CEF, TDR, MSE, PJK), Seattle, WA; the Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington School of Public Health (LSG), Seattle, WA; the Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine (TDR, MSE), Seattle, WA; and the Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, University of Washington School of Medicine (PJK), Seattle, WA. Received August 9, 2009; revisions received September 11 and November 8, 2009; accepted December 6, 2009. Address for correspondence and reprints: Peter J. Kudenchuk, MD; e-mail: [email protected]. the resuscitation of hemodynamically unstable cardiac arrest in humans. Antiarrhythmic agents currently recommended by the American Heart Association (AHA) for the treatment of cardiac arrest include amiodarone, lidocaine, and magnesium.4 Procainamide is a Vaughn Williams Class IA antiarrhythmic with conduction-slowing and vasodilatory properties. Currently, the AHA recommends procainamide for hemodynamically stable ventricular arrhythmias and atrial arrhythmias in patients with preserved ventricular function, but makes no recommendations about the use of the drug for the treatment of cardiac arrest.4 Indeed, the sum of the world’s published experience with intravenous (IV) procainamide in cardiac arrest is limited to the reporting of outcomes in a subgroup of only 20 patients from a larger observational study7 and no randomized clinical trials. For patients with cardiac arrest in whom defibrillation or first-line cardiac medications are unsuccessful, alternative treatments are limited. A better understanding of alternative treatments such as procainamide may Flutter y TV estable, no PCR ª 2010 by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00763.x ISSN 1069-6563 PII ISSN 1069-6563583 617 Procainamide and Survival in Ventricular Fibrillation Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest David T. Markel, Laura S. Gold, MSPH, Judith Allen, MPH, Carol E. Fahrenbruch, MSPH, Thomas D. Rea, MD, MPH, Mickey S. Eisenberg, MD, PhD, and Peter J. Kudenchuk, MD 620 Abstract Markel et al. • PROCAINAMIDE IN CARDIAC ARREST Objectives: Procainamide is an antiarrhythmic drug of unproven efficacy in cardiac arrest. The association between procainamide and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was investigated to better determine the drug’s potential role in resuscitation. Table 1 Baseline Characteristics of the 665 The Study Patients Methods: authors conducted a 10-year study of all witnessed, out-of-hospital, ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT) cardiac arrests treated by emergency medical services (EMS) in King County, Washington. Patients were considered eligible for procainamide if they received more than three defibrillation shocks and intravenous (IV) bolus lidocaine. Four logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) describing the relationship All Procainamide Recipients between procainamide and survival. Characteristic Patients Not Treated With Procainamide (n = 489) (n = and 176) Results: Of the 665 eligible patients, 176 received procainamide, 489 did not. On average, procainamide recipients received more shocks and pharmacologic interventions and had lengthier resuscitamedian (n) 63.0 (±12.5), 63.0procainamide recipients had a lower63.7 tions. Adjusted for their clinical and resuscitation characteristics, likelihood of survival to hospital discharge62.7 (OR = (±12.7), 0.52; 95% CI = 0.36 to 0.75). Further adjustment for63.5 63.0 (152) receipt of other cardiac medications during resuscitation negated this apparent adverse association 64.9 (±11.5), 64.0 (24) 64.7 (OR = 1.02; 95% CI = 0.66 to 1.57). Age (yr), mean (±SD), (±13.9), 64.0 Males (±13.8), 64.0 (388) Females (±14.7), 65.0 (101) Male sex, n (% of group) Conclusions: In this observational study of 152 (86.4) 388 (79.3) out-of-hospital VF and pulseless VT arrest, procainamide as Arrest in public, n (% of group) 174 (35.6) second-line antiarrhythmic treatment was 62 not (35.2) associated with survival in models attempting to best account for confounding. The results suggest procainamide, as administered in this investigation, Bystander CPR, n (% of group) 112 that (63.6) 338 (69.1) does not have a large impact on outcome, but cannot eliminate the possibility of a smaller, clinically releContinuous variables, mean (±SD), median vant effect on survival. Dispatch to arrival of first EMS unit 4.9 (±2.2), 5.0 (valid n = 161) 4.8 (±2.0), 4.8 (valid n = 453) ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 2010; 17:617–623 ª 2010 by the Society for Academic Emergency (BLS or ALS) (minutes)Medicine Dispatch to ALS arrival (minutes) 8.3 cardiopulmonary (±3.6), 8.0 (valid n = 176) 8.5 (±3.7), 8.0 (valid n = 461) Keywords: antiarrhythmia agents, arrhythmia, resuscitation, survival Total number of shocks (BLS and ALS) 12.4 (±6.6), 10.0 7.0 (±3.2), 6.0 Estimated length of resuscitation (minutes)* 47.3 (±15.9), 46.9 (valid n = 149) 38.5 (±13.3), 37.5 (valid n = 423) EMS interventions, n (% ntiarrhythmic of group) medications are frequently dur- the resuscitation of hemodynamically unstable cardiac arrest in humans. Antiarrhythmic agents currently recing resuscitation from cardiac arrest, although Epinephrine 174 (98.9) 415 (84.9) ommended by the American Heart Association (AHA) research supporting their efficacy in this setting Magnesium 58 (33.0) 49 (10.0) 1–4 is scarce. Supporting evidence is stronger for their use for the treatment of cardiac arrest include amiodarone, Bretylium 30 (17.0) 26 (5.3) in the treatment of hemodynamically stable arrhyth- lidocaine, and magnesium.4 5 Medication dosages (mg), mean medianresults (n) from some mias, which, along (±SD), with encouraging Procainamide is a Vaughn Williams Class IA antiarEpinephrine (mg) 6.8to(±4.2), 6.0 with (174)conduction-slowing and vasodilatory 4.4 (±3.2), 4.0 (414) animal studies,6 has spurred the extension of their use rhythmic properties. Currently, procainLidocaine (mg) 266.5 (±67.5), 300.0 (175) the AHA recommends 189.0 (±79.0), 200.0 (488) amide 2.0 for (58) hemodynamically stable ventricular2.7 arrhythMagnesium (g) From the University of Washington School of Medicine (DTM), 2.6 (±1.4), (±1.9), 2.0 (49) Seattle, WA; Division of Emergency Medical Services, Public mias and atrial arrhythmias in patients with preserved Bretylium (mg)!Health Seattle and King County (DTM, LSG, JA, CEF, 870.0 (±481.5), 950.0 (30) 692.3 (±376.2), 500.0 (26) TDR, ventricular function, but makes no recommendations Procainamide (mg) 742.9 about the500.0 use of the drug for the treatment — of cardiac MSE, PJK), Seattle, WA; the Department of Epidemiology, Uni-(±341.6), versity Outcomes, number (% of ofWashington group) School of Public Health (LSG), Seattle, arrest.4 Indeed, the sum of the world’s published experience with intravenous (IV) procainamide305 in cardiac WA; the Department of Medicine, University of Washington Admitted alive to hospital 80 (45.5) (62.4) School of Medicine (TDR, MSE), Seattle, WA; and the Depart- arrest is limited to the reporting of outcomes in a subSurvived to hospital discharge 33 (18.8) 1 56 (31.9) group of only 20 patients from a larger observational ment of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, University of Wash- A ington School of Medicine (PJK), Seattle, WA. study7 and no randomized clinical trials. For patients with resuscitation; cardiac arrest in EMS whom = defibrillaReceived August BLS 9, 2009; received September 11 and ALS = advanced life support; = revisions basic life support; CPR = cardiopulmonary emergency medical services. tion or first-line cardiac medications are unsuccessful, 8, 2009; accepted December 6, 2009. *Calculated as theNovember interval between arrival of first EMS personnel and the final time recorded in the prehospital record when Address for correspondence and reprints: Peter J. Kudenchuk, alternative treatments are limited. A better understandresuscitation efforts and ⁄ or the patient was readied for ing transport to hospital. of alternative treatments such as procainamide may MD;ceased e-mail: [email protected]. !Bretylium was removed from resuscitation guidelines beginning January 1, 2001; 56 patients were treated with bretylium prior to this date, 30 of whom also received procainamide and 26 of whom did not. ª 2010 by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00763.x ISSN 1069-6563 PII ISSN 1069-6563583 617 Drogas utilizadas en RCP • Vasopresores • Antiarrítmicos • Buffers • Otras: Estrógenos, nitroprusiato, corticoides. 51 Bicarbonato de sodio • Desde las guidelines de 1986 que NO está recomendado. • “ Puede ser utilizado a discreción del líder del equipo” • No hay buen nivel de evidencia para estos estudios. • Conductas pendulares Resuscitation 54 (2002) 47 !/55 www.elsevier.com/locate/resuscitation Clinical use of sodium bicarbonate during cardiopulmonary resuscitation* is it used sensibly?! / Gad Bar-Joseph a,c,*, Norman S. Abramson a, Linda Jansen-McWilliams b, Sheryl F. Kelsey b, Tatiania Mashiach d, Mary T. Craig a, Peter Safar a, Brain Resuscitation Clinical Trial III (BRCT III) Study Group a Safar Center for Resuscitation Research, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA b Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Rambam Medical Center and the Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, Technion */Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 31096, Israel d Quality Assurance Department, Rambam Medical Center and the Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, Technion */Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 31096, Israel c • Se dieron cuenta con este registro que BS Received 27 August 2001; received in revised form 21 January 2002; accepted 21 January 2002 era utilizado un 55% de las reanimaciones de PCR. Abstract This study retrospectively analyzed the pattern of sodium bicarbonate (SB) use during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the Brain Resuscitation Clinical Trial III (BRCT III). BRCT III was a prospective clinical trial, which compared high-dose to standard-dose epinephrine during CPR. SB use was left optional in the study protocol. Records of 2915 patients were reviewed. Percentage, timing and dosage of SB administration were correlated with demographic and cardiac arrest variables and with times from collapse to Basic Life Support, to Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) and to the major interventions performed during CPR. SB was administered in 54.5% of the resuscitations. The rate of SB use decreased with increasing patient age */primarily reflecting shorter CPR attempts. Mean time intervals from arrest, from start of ACLS and from first epinephrine to administration of the first SB were 299/16, 199/13, and 10.89/11.1 min, respectively. No correlation was found between the rate of SB use and the pre-ACLS hypoxia times. On the other hand, a direct linear correlation was found between the rate of SB use and the duration of ACLS. We conclude that when SB was used, the time from initiation of ACLS to administration of its first dose was long and severe metabolic acidosis probably already existed at this point. Therefore, if SB is used, earlier administration may be considered. Contrary to physiological rationale, clinical decisions regarding SB use did not seem to take into consideration the duration of preACLS hypoxia times. We suggest that guidelines for SB use during CPR should emphasize the importance of pre-ACLS hypoxia time in contributing to metabolic acidosis and should be more specific in defining the duration of ‘protracted CPR or long resuscitative efforts’, the most frequent indication for SB administration. # 2002 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. • 2915 pacientes • Conclusión: enfatizan en intentar estimar Keywords: Acid !/base; Acidosis; Bicarbonate; Sodium bicarbonate; Buffer therapy; Cardiac arrest; Cardiopulmonary resuscitation; Advanced life support tiempos de PCR. En estadíos precoces de acidosis, podría ser útil 1. Introduction Excessive lactate production always results from tissue hypoxia and anaerobic metabolism. Since severe ! Presented in part at the 7th World Congress of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine, Ottawa, Canada, July 1997. * Corresponding author. Tel.: "/972-4-8542855/9834948; fax: "/9724-8542864 E-mail address: [email protected] (G. BarJoseph). metabolic acidosis was considered detrimental during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), buffering with sodium bicarbonate (SB) was intuitively and empirically included in its initial pharmacological armamentarium [1]. SB was subsequently recommended as a first line drug in the first American Heart Association’s (AHA) Standards for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) [2]. Its use was re-evaluated in the 1986 update of the ACLS Guidelines, where it was no longer recommended, but rather ‘could be used at the discretion of the team 0300-9572/02/$ - see front matter # 2002 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 3 0 0 - 9 5 7 2 ( 0 2 ) 0 0 0 4 5 - X Bicarbonato de sodio Grado de recomendación AHA: Nivel III Considerar en situaciones especiales: Acidosis severa Bloqueadores canales de Sodio Hiperkalemia Drogas utilizadas en RCP • Vasopresores • Antiarrítmicos • Buffers • Otras: magnesio,nitroprusiato, estrógenos, aminofilina. 55 Magnesio • • Cofactor para la utilización celular de ATP • • • PCR: Podría ayudar. Uso de rutina no es útil. Deficiencia de Mg++ se asocia a arritmias, ICC y muerte súbita. Evidencia basado en reportes de casos Estudio MAGIC Magnesio • Dosis: Carga 1 a 2 g (8-16mEq) diluido en 50 a 100 ml sg5% en 5 a 60’. Infusion de 0,5-1 g/h. • • En emergencias 1-2g en 10 ml a pasar en 2 min. • • Relacionado a embarazo. Efectivo y droga de elección en manejo de Torsade de Pointes (Sindromes de QT largo). Grado de recomendación: IIb ( torsade) Concepto de post acondicionamiento isquémico Prolonged CPR Hemodynamic study SNPeCPR (8 animals) 25 min If ROSC 8 min of untreated VF S-CPR (8 animals) “eCPR” NO SNP (8 animals) Yannopoulos, Matsuura, Schultz, et al. Crit Care Med. 2011 Feb 24. 24-hour survival Carotid Blood Flow (ml/min) 350 SNPeCPR S-CPR +epi ACD CPR+ITD+AB 300 250 200 †* †* 150 †* 100 * * 50 * †* †* * * 0 Baseline 5m 10m 15m CPR 20m 25m End-tidal CO2(mmHg) 40 SNPeCPR 35 S-CPR+ epi ETCO2 ACD CPR+ITD+AB 30 25 †* †* †* 20 †* †* 15 * 10 * * 5 * * 0 Baseline 5m 10m 15m CPR 20m 25m 24 Hour Overall Performance Category Score 5 (dead) * * 4 3 Good neurological outcomes 2 1 SNPeCPR eCPR S-CPR Background Endogenous adenosine might cause or perpetuate bradyasystole. Our aim was to determine whether aminophylline, an adenosine antagonist, increases the rate of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after out-ofhospital cardiac arrest. Lancet 2006; 367: 1577– University of British Col Vancouver, BC, Canada (R B Abu-Laban MD, C M McIntyre MD, Methods In a double-blind trial, we randomly assigned 971 patients older than 16 years with asystole or pulseless Prof J M Christenson MD, electrical activity at fewer than 60 beats per minute, and who were unresponsive to initial treatment with epinephrine C A van Beek BSN, and atropine, to receive intravenous aminophylline (250 mg, and an additional 250 mg if necessary) (n=486) or Prof G D Innes MD, Riyad B Abu-Laban, Caroline M McIntyre, James M Christenson, Catherina A van2001 Beek, Grant Innes, Robin K O’Brien, Karen P Wanger, placebo (n=485). The patients were enrolled between January, andD September, 2003, from 1886 people who had R K O’Brien PharmD, K P Wanger MD, R Douglas McKnight, Kenneth G Gin, Peter J Zed, Jeffrey Watts, Joe Puskaric, Iain A MacPhail, Ross G Berringer, Ruth A Milner had cardiac arrests. Standard resuscitation measures were used for at least 10 mins after the study drug was R D McKnight MD, K G Gin administered. Analysis was by intention-to-treat. This trial is registered with the ClinicalTrials.gov registry with the P J Zed PharmD, I A MacPh Summary R G Berringer MD, number NCT00312273. Background Endogenous adenosine might cause or perpetuate bradyasystole. Our aim was to determine whether Lancet 2006; 367: 1577–84 A Milner MSc); British aminophylline, an adenosine antagonist, increases the rate of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after out-of- University of BritishRColumbia, Columbia Ambulance Se Vancouver, BC, Canada cardiac arrest. Findings hospital Baseline characteristics and survival predictors were similar in both groups. The median time from theMD,Victoria, BC, Canada (R B Abu-Laban C M McIntyreof MD, (J M Christenson, arrival ofMethods the advanced life-support to 971 study drugolder administration was asystole 13 min. proportion In a double-blind trial, paramedic we randomly team assigned patients than 16 years with or The pulseless Prof J M Christenson MD, K P Wanger, J Watts EMApatients who hadactivity an ROSC wasthan 24·5% in the aminophylline group and 23·7% in thetreatment placebowith group (difference 0·8%; electrical at fewer 60 beats per minute, and who were unresponsive to initial epinephrine C A van Beek BSN, J Puskaric EMA-3); and Ce Prof G Ddrug Innes MD, and atropine, to receive intravenous (250 mg, andwith an additional 250 tachyarrhythmias mg if necessary) (n=486) 95% CI –4·6% to 6·2%; p=0·778). Theaminophylline proportion of patients non-sinus afterorstudy R K O’Brien PharmD,for Clinical Epidemiolog placebowas (n=485). The in patients were enrolled between 2001 and September, from 1886 peopleSurvival who had to hospital administration 34·6% the aminophylline groupJanuary, and 26·2% in the placebo2003, group (p=0·004). K P Wanger MD, Evaluation, Vancouver, B had cardiac arrests. Standard resuscitation measures were used for at least 10 mins after the study drug was R D McKnight MD, K G Gin MD, admission and survival to hospital discharge were not significantly different between the groups. A multivariate Canada (R B Abu-Laban, administered. Analysis was by intention-to-treat. This trial is registered with the ClinicalTrials.gov registry with the P J Zed PharmD, I A MacPhail MD, C A van Beek, R A Milner) logistic regression analysis showed no evidence of a significant subgroup or interactive effect from aminophylline. Aminophylline in bradyasystolic cardiac arrest: a randomised placebo-controlled trial R G Berringer MD, R A Milner MSc); British Correspondence to: Columbia Ambulance DrService, Riyad B Abu-Laban, Victoria, BC, Canada Department of Emergenc (J M Christenson, Medicine, Vancouver Gen K P Wanger, J Watts EMA-3, Hospital, J Puskaric EMA-3); and Centre Vancouver, for Clinical Epidemiology and BC V5Z 1M9, Canada Evaluation, Vancouver, BC, abulaban@interchange. Canada (R B Abu-Laban, C A van Beek, R A Milner) number NCT00312273. FindingsAlthough Baseline characteristics and survival predictors were similar in both groups. The the Interpretation aminophylline increases non-sinus tachyarrhythmias, wemedian notedtime no from evidence that it arrival of the advanced life-support paramedic team to study drug administration was 13 min. The proportion of significantly increases the proportion of patients who achieve ROSC after bradyasystolic cardiac arrest. patients who had an ROSC was 24·5% in the aminophylline group and 23·7% in the placebo group (difference 0·8%; 95% CI –4·6% to 6·2%; p=0·778). The proportion of patients with16–24 non-sinus tachyarrhythmias after study drug arrest. Introduction We undertook this study to to assess the effect of administration was 34·6% in the aminophylline group and 26·2% in the placebo group (p=0·004). Survival hospital aminophylline during cardiopulmonary resuscitation Out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest treated by admission and survival to hospital discharge were not significantly different between the groups. A multivariate logistic regression analysis no evidence of a significant subgroup interactivewith effect out-of-hospital from aminophylline. (CPR) of orpatients bradyasystolic emergency medical services hasshowed an estimated incidence Correspondence to: of 55 per 100 000 person-years, which translates to about cardiac arrest unresponsive to initial therapy. Dr Riyad B Abu-Laban, Interpretation Although aminophylline increases non-sinus tachyarrhythmias, we noted no evidence that it Department of Emergency 155 000 episodes annually in the USA.1 Bradyasystole is significantly increases the proportion of patients who achieve ROSC after bradyasystolic cardiac arrest. Medicine, Vancouver General the first recorded rhythm in up to 52% of cardiac arrests, Methods Hospital, Vancouver, 16–24 1M9,3, Canada and manyIntroduction additional patients with an initial cardiac arrest arrest. We undertook this trial between Jan 21, 2001, and Sept We undertook this study to assess the effect of BC V5Z [email protected] during cardiopulmonary resuscitation sudden cardiac arrest treated by rhythm Out-of-hospital of ventricular fibrillation deteriorate to aminophylline 2003, at eight advanced life-support paramedic stations (CPR) of patients with out-of-hospital bradyasystolic emergency medical services has an estimated incidence 2,3 bradyasystole after defibrillation efforts. Fewer than 3% in the greater Vancouver and Chilliwack region in of 55 per 100 000 person-years, which translates to about cardiac arrest unresponsive to initial therapy. Canada. This region has a population of more than two of patients presenting with bradyasystole survive to 155 000 episodes annually in the USA.1 Bradyasystole is hospital discharge; however, more 17% of all cardiac million, served by the British Columbia Ambulance the first recorded rhythm in upthan to 52% of cardiac arrests, Methods 4 and manyhad additional with an initial cardiac arresta We undertook this trial between Jan 21,arrest 2001, and Sept 3,are treated arrest survivors initialpatients bradyasystole. Thus, even Service. Out-of-hospital cardiac patients rhythm of ventricular fi brillation deteriorate to 2003, at eight advanced life-support paramedic stations small improvement in survival from 2,3bradyasystolic by paramedics with protocols based on American Heart bradyasystole after defibrillation efforts. Fewer than 3% in the greater Vancouver and Chilliwack region in cardiac arrest could save thousands of lives. Association guidelines,25 and are not taken to hospital of patients presenting with bradyasystole survive to Canada. This region has a population of more than two Adenosine is discharge; an endogenous purine that million, unless served a perfusing develops,Ambulance a shockable rhythm hospital however, more thannucleoside 17% of all cardiac by the rhythm British Columbia 4 depressesarrest the survivors sinoatrial blocks atrioventricular persists, or there are extenuating circumstances such as had node, initial bradyasystole. Thus, even a Service. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients are treated smallinhibits improvement in survivalactivity from bradyasystolic paramedics with protocols based on American Heart conduction, the pacemaker of the His- byhypothermia or intermittently palpable pulses. 25 gen may not only have a direct developed by reviewing some of the pertherapeutic benefit in some instances, tinent clinical observations, extensive exestrogen administration may also be perimental data, and the related safety synergistic with other resuscitative in- and feasibility of this treatment. The disRationale (10, for 18, routine immediate administration of intravenous will also detail some of the curterventions 19, 22,and 27–29, 32). cussion rent scientific estrogen for all critically ill and patients initiatives related to sex A significant body of laboratory evi-injured dence, bridging across a variety of species hormone therapy, and it will provide recommendations for future research in Jane aG. breadth Wigginton, MD; Paul E. Pepe, MD; models, Ahamed H. Idris, MD and of experimental nowIn addition supports the concept that estrogen what is now being called resuscitative to a number of very compelling clinical obser- efit is profound. Even if estrogen only changes the outcome in endocrinology. vations, extensive body of therapeutic extremely supportive experimen- a relatively small percentage of applicable cases, the potential may beanan effective intervental data has generated a very persuasive argument that intra- impact may still be of dramatic proportions in terms of the of Internal Medicine (PEP, tion for a spectrum of severe physiologic venous estrogen should be routinely administered, as soon as absolute number of lives saved and the resources spared edicine) (PEP, JGW, AHI), insults Cohort studies of sex hormone possible, toand all persons identified as having a critical illness or worldwide. Resources may be spared not only in terms of injuries (12–28). Although injury. Although, to date, definitive gold-standard clinical trials diminishing the economic impact of death and long-term disof Public Health (PEP), The influences resuscitation clinical trials are stillargument lacking, are lacking, what has made this provocative even ability, but also in termsin of preventing extended intensive care stern Medical Center and definitive more convincing is the longstanding, documented safety of unit stays and treatment of preventable complications that striking experimental spital System, Dallas TX; the intravenous estrogen for various illnessesevidence, and conditions as as result in longer recovery. (Crit Care Medand 2010;Cardiac 38[Suppl.]:ArFemale Sex Hormones Sex, Drugs and R&R (Reanimation & Resuscitation): well as the relative ease and inexpensive cost of treatment. As S620 –S629) Center for Resuscitation well as several compelling clinical obser- rest. In the mid-1990s there was an existsuch, even routine prehospital administration becomes exKEY WORDS: resuscitation; cardiopulmonary resuscitation; carDallas, TX. Sex Hormone Interventions in Resuscitation vations haveforspawned a very More convincing arrest; hemorrhagic shock; trauma; traumatic brain injury; tremely feasible a myriad of conditions. importantly, diac ing controversy regarding women having ational Institutes of Health the worldwide magnitude of potential patients who could ben- burns; estrogen; progesterone; antiapoptotic; anti-inflammatory argument that intravenous (IV) estrogen, cience Award grant numworse outcomes than men in heart attack and perhaps other female sex hormones JJaannee G . W i g g i n t o n , M D , F A C E P G. Wigginton, MD, FACEP and stroke (5– 8, 37– 40). It was argued, ver the last several decades, effects in numerous conditions ranging conditions over the past several decades t off-label uses of estro(such progesterone), should be rouAssistant Professor, Surgeryas / Emergency Medicine however, that theasdata reflected other as well the relatively inexpensive costsothere has been an ongoing from global ischemic insults and masDrug Administration has and Clinical Scholar, Department of Clinical Sciences of treatment (34 –36). and increasing interest in sive systemic inflammatory responses tinely administered to all critically ill and ciological and perceptual factors and not University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center be- to devastating focal injury nal new drugThe applications In the following discussion, the ratioidentifying differences and apoptoand the Parkland Health and Hospital persons, soonsisasin possible routinely administering IV estrotween men and womenSystem; inand termsas of their vital organs (10an –31).underlying Further- nale for physiologic disadvantage. ormally study the use of injured respective physiologic responses to crit- more, an exogenous infusion of estro- gen to the critically ill and injured will be Medical Director for Resuscitation Research, after onset of their specific malady (10, For example, oned in this Assistant text. it was hypothesized that developed by reviewing some of the perical illness and injury as well as their Dallas Metropolitan BioTel (EMS) System, Dallas, Texas, USA gen may not only have a direct sclosed any potential con- 12, tinent clinical observations, extensive ex- atrelative rates of survival and recovery therapeutic benefit in some instances, 29 –33). perhaps women did not seek medical (1–9). Among a number of proposed estrogen administration may also be perimental data, and the related safety What makes this provocative and feasibility of thistheir treatment. The dismechanisms for the identified differ- synergisticargutention as or that symptoms with other resuscitative in- readily ing this article, E-mail: cussion will also detail some of the curences, the potential and powerful influP ,, M M ,, M P (10, 18, 19,were 22, 27–29, Paauull E E.. P Peeppeement MD D,,even MP PH Hmore MA AC C P,, FFC CC CM Mterventions persuasive is the longnot32).recognized as “typical.” At the ence of sex hormones has been gaining A significant body of laboratory evi- rent scientific initiatives related to sex hormone therapy, and it will provide recsignificant attention (2, 10 –12). Estrostanding, documented safety dence, and simplicof Medicine, Surgery, Pediatrics, Public Health e Society of Professor Critical Care sameof species time, it was also conjectured that bridging across a variety gen, in have protective and a breadth of experimental models, ommendations for future research in and Riggs Family Chair in particular, Emergencymay Medicine iams & Wilkins of a single dose of IV estrogen women may not receive interventions as University of Texasity Southwestern Medical Center now supports the concept that estrogen what is now being called resuscitative Health and Hospital System, Dallas, USAillnesses may be an effective interven- endocrinology. for various and therapeutic 13e3181f243a9and the Parklandadministration aggressively as men (37, 40). ry as well as their vival and recovery mber of proposed e identified differand powerful influs has been gaining (2, 10 –12). Estromay have protective O From the Departments of Internal Medicine (PEP, tion for a spectrum of severe physiologic Director, City of Dallas Emergency Services forAHI), AHI),Medical Surgery (Emergency Medicine) (PEP, JGW, insults and injuries (12–28). Although Public Safety, Public Health, Pediatrics (PEP),Homeland and School of Security Public Healthand (PEP),Research The definitive clinical trials are still lacking, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Crit Care the striking experimental evidence, as the Parkland Health and Hospital System, Dallas TX; and The Dallas Fort Worth Center for Resuscitation well as several compelling clinical obserResearch (PEP, JGW, AHI), Dallas, TX. vations have spawned a very convincing Recent studies, including Wigginton’s longitudinal, study of cardiac arrests Funded, in part,recent by the National Institutes population-based of Health argument that intravenous (IV) estrogen, (Clinical and Translational Award grant num(n =~10,000 out-of-hospital subjects) andScience Topjian’s corresponding in-hospital registry study and perhaps other female sex ber: 5 UL1 RR024982-04). (n=~20,000 in-patient subjects) clearly have demonstrated very significant outcome differences hormones does suggest off-label uses those of estro-women (such as progesterone), should be roubetween men and women,The andarticle most profoundly favoring of child-bearing age. These Synopsis Cohort studies of sex hormone influences in resuscitation MedFemale 2010SexVol. 38, No. 10 (Suppl.) Hormones and Cardiac Arrest. In the mid-1990s there was an existing controversy regarding women having worse outcomes than men in heart attack and stroke (5– 8, 37– 40). It was argued, however, that the data reflected other so- VF/Pulseless VT Finalmente... Three-Phase Model of Resuscitation Weisfeldt ML, Becker LB. JAMA 2002: 288:3035-8 100% Myocardial ATP Drogas precoces!!! 0 Circulatory Phase Electrical Phase Metabolic Phase Texto MASAJE CARDÍACO 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 Arrest Time (min) 14 16 18 20