- Ninguna Categoria

Quiroga's El Almohadón de Plumas: Intertextual Analysis

Anuncio

SLEEPING BEAUTY MEETS CO UNT DRACULA .

INTERTEXTUA LITIE S IN HORACIO QUIROGA'S

EL ALMOH AD6N DE PLUMAS .

Pat ricia Anne Odber de Baub eta

Unive rs ity of Birmingham

El intento de Quiroga es torpe y trivial , y la

perver si6n latent e en el tema se convierte en un

mero esca lofrio s in rnisterio' .

This essay will not d eal w it h the issue of authorial

intentiona li ty. Instead, w e prop ose to demonstrate that EI

almohad6n de plumas is neith er torpe nor trivial. Rather, it is

particularly forceful p iece of writing and Rub en Cotelo's

critical judgment com pletely fails to take account of a number

of elements present in the text of El almohad6n de plumas which

enhance rather than detract from its effectiveness. We shall

examine Q uiroga's 'doble uso del horror', though no t from the

same perspective as Etcheverry/, hi s handling of fanta sy

elernents'', and the rea de r's resp onse to a ll of these. However,

before embarki ng on such a discussion , it would be useful to

clarify w ha t is under sto od by 'effectiveness', and Michael

Riffaterre's definition offers us as useful a point of de pa rture as

any:

The effec tiveness of a text may be defined as th e

degree of its perceptibility by the read er; the

more it attracts its attention, th e better it resist s

his man ipulations and withstands the att rition of

h is s uccessiv e re adin gs, th e mor e it is a

Fragmentos volA "e2, pp. 19-39

20

Patricia Anne Odber de Baubeta

monument rather than just an ephemeral act of

communication, and therefore the more literary

it is".

Quiroga's story has certainly attracted the attention of

numerous critics (and 'ordinary' readers); it stands up to

repeated readings; it challenges our perceptions and there is no

doubt that it lends itself to more than one interpretations.

However, we do need to identify and analyse those

mechanisms that render the story effective. It is manifestly

inadequate to suggest that the story is well-written because it

complies with Quiroga's own Decalogo del perfecto cuentista.

Instead, we prefer to argue that the effectivenesso of £1

almohadtm de plumas also stems from its relationship with the

intertext, both that of the writer and that of the reader. By

intertext, we mean:

The corpus of texts the reader may legitimately

connect with the one before his eyes, that is, the

texts brought to mind by what he is reading".

The specific reader response which we are concerned is,

according to Riffaterre, the 'intertextual drive':

The urge to understand compels readers to look

to the intertext to fill out the text 's gaps, spell out

its implications",

Intertextuality may fulfil several functions . According to

Laurent Jenny, its principal function is to transform the

significance of the text", and that is arguably the role it assumes

in Quiroga's short story. At the same time, there are discernible

conflicts and tensions in the intertext of EI almohadon de plumas

that enhance the horror of the story. Because of one set of

elements in the intertext, the reader is led to expect one kind of

denouement; because of other intertextual consituents, he is

confronted with another. This dissonance in the intertext is to

some extent responsible for the shock and repugnance

experienced by the reader, the 'efecto' that the author achieves",

There are other factors in play, among them the surprise ending

with its 'sup ues to toque cientfflco", though this has been

Sleeping Beauty Meets...

21

perceiv ed as ironic. Margo Glantz considers that the true horror

of £1 almohad6n de plumas derives from the locating of the

monster in the midst of ordinary, everyday life:

La exp licaci6 n racionalista parece hundir en el

an onim ato cotidiano la presencia del

inse ct o- vampiro , p ero es justa mente esta

coexistencia tan cercaria, este simbolismo de

factura tan concreta, 10que produce el terror mas

hondo!' ,

The intertex t of the £1 almohad6n de plumas consists of at least

two di stinct but related traditions: the fairy tale, notably

Sleeping Beauty, and th e go thic/vamp ire story, particularly

Bram Stok er's Dracula". The forme r is a genre with which we

are all fa miliar' :', and eve n though Sleeping Beauty may not be

uppermost in our thoughts as w e read £1 almohad6n de plumas,

our read in g experience of this and othe r fair y tales is brought

to bear on Quiroga's short story, cond itioning our expectations

(particularly of a happy end ing), and serving to point up the

hor ror of the conclusion".

Fairy tales a re the first form of the story with which many

of us have our first contac t, and although it would be ab surdly

simplistic to presume that Quiroga read Sleeping Beauty then

d ecided to use it or allude to it in his work IS, there is no doubt

tha t on several occasions he makes un equivocal statements

ab out his pr eference for a genre which owes much to th e fairy

tales and presen ts problem s or cha llenges identical to those of

its precu rsor" . Certainly, ther e is firm evide nce that fairy tales

con stituted part of Quiroga's vast read ing experience and are

th erefore as sig n ifica n t in his interte xt as th ey are in the

read er 's17.

The firs t third of this story contains a series of elements

w hich we might find in a convention al fairy tale. In fact, on

exa mining Sleeping Beauty, it is po ssibl e to tra ce a number of

apparent parallels between the tw o stories. Howe ver, reading

Q uiroga's £1almohad6n de plumas is in so me ways like hearing

a d is co rdant e ch o o f the Sleeping Beauty. Mo st of the

reminiscen ces occur very ea rly in Quiro ga 's sto ry, but th ey are

crucial for th e reader's response later on. The omniscient

22

Patricia Anne Odber de Baub eta

third-person narrator makes a series of observations that serve

as reminders of the Sleeping Beauty story18, but which also create

an atmosphere in which th e reader will feel uncomfortable and

disoriented, sensing that eve nts are not following any safe,

predictable pattern. Ins tead he becomes increasingly aware of

what might be term ed 'distorted in tertextualities', In Sleeping

Beauty, as in so many other fairy tales , the hero /prince and

heroine /princess ge t married and, sooner or later, depending

on the version w e read, live happily ev er , Quiroga begins his

narrative with w hat sho uld be the happ ies t of all occasions, a

marriage, but his story becomes progressively mo re hopeless,

un til it ends with th e death of the 'fai ry prince ss' Alici a. Because

the story opens with such a d isconcerting remark as 'Su luna

de m iel fue un largo escalofrio' (p . 157) the reader is bound to

question what is h appeni ng 19, This is not th e usual way to

describe a honeymoon, an event tr ad ition ally associated with

joy" la ughter, mo m en ts of shared hap piness and socially

ap proved sex ua l fulfil me nt. The connotations of 'escalofrio', on

the other hand, are more us ually fear, terror or pain. The

tension set up by this antithetical relationship between noun

and adjective refl ects the relationship between text an d

intertext20,

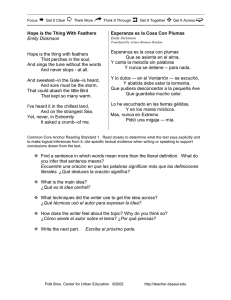

According to one theorist, there are several forms of

intertextuality, among them citation and allusiorri'. Here we

prefer to talk in terms of correspondences between text and

intertext. As far as Sleeping Beauty and El almohadon de plumas

are concerned, there are a number of correlations. (For the

purposes of this comparison, we shall be using Angela Carter 's

translation of Perrault's version. Grimm's version is simpler,

less frightening, and completely omits the ogress epi sode, as

can be seen in the co mparison that follow s 22 ,

Perrault's version of

The Sleeping Beauty:

Grimm's version, Briar-Rose

or The Sleeping Beauty:

King and Queen unab le to

have ch il d r e n. Go o n

pilgrimages to holy places,

finally she ha s a daughter.

The Queen is bathing when a

crab comes out of the water to

tell her that she will have a

daughter.

Sleeping Beauty Meets...

Godmothe rs invited - all the

fai ries in the kingdom that

th e y co ul d find - 7 in

number.

23

There are 13 fairies in th e land

but because the King only has

12 gold pl ates, only 12 are

invited to th e christening.

Each fairy to giv e the ba by a

gift s o tha t she would be

perfect. Old fairy no t inv ited

because she hadn 't left her

lower for more th an 50 years

- eve ryone th ought she wa s

dead or under a sp ell. Because

she isn't e xpected, no gold

plate or cu tlery. Takes offence

and mutters so me threats . A

younger fai ry hides behin d a

wall-hanging to mak e good

any damage the O ld Fairy

might do. Says the prin cess

will pi erce h er hand on a

spind le and die. Good fairy

modifies th e 'gift'; princess

will not die but sleep for 100

years th en be awoken by a

prin ce. Kin g prohibit s

sp indles, under pain of death .

15 ye ars later th ey are on

h olida y at a sum mer

resid ence and the princess

climbs up to the attic.

Find s a n old woman

sp in n ing, tries for herself,

pierces her hand and falls into

a deep sleep .

Th e princess climbs up to a

tower in their ow n castle, not

a holiday hom e.

The Good Fairy hastens to the

palace and casts a spell on

eve ryone except her parents

Every o ne go es t o s lee p,

inclu ding t he Kin g a n d

Queen.

24

Patricia Anne Odber de Baubeta

so that the princess won' t be

lonely when she w akes up .

100 years later, there is a new

king, from anothe r family. His

son is curious abo ut the forest

where he goes hunting; finds

o u t abo u t the prince s s,

legends, and decides to check

ou t the fores t. Kneels in front

of her and she wakes up. No

kiss.

They talk, the palace awa kens

an d they get ma rried .

The prince returns hom e the

next d ay but d oes not tell his

parents what has happen ed .

Spe n ds ni gh t s w it h th e

pri n cess but goes ho me . 2

yea rs la te r th ey h av e tw o

ch ildren, a girl, Dawn, and a

bo y, Da y, wh o is m ore

beautiful than his sister. The

prince doesn't tell his moth er

because he is afraid of her s he is a n ogress , a nd is

tempted to ea t children . Once

his fa ther has d ied he

announces his marriage and

br in gs h is fam ily to th e

palace. Then he goes to war

a n d le a v es his mot he r in

cha rge of the kingdom. She

to

ea t

he r

d ecid e s

Var iou s princes try to rescue

h e r b u t get caug h t in t he

hedge and di e a miserable

death. A prince arrives, the

hedge opens up for him , and

h e walks throu gh . The

princes s wa kes u p a t th e

moment of the kiss.

The pala ce awak en s and

carries on as if ther e had no t

a n int erval of a hundred

yea rs . Briar-Rose and th e

prince ge t married and 'live

happily to th e end of their

days' .

Sleeping Beauty Meets...

25

grandchild ren and daughterin -law, b u t is foiled by the

butler w ho saves them. When

she even tually find s out she

has been tricked, she is about

to put th em to d eath, but the

king returns home in time to

save them, she dies in st ead

and the family live happily

ever after.

What are the points of contact between Sleeping Beauty and El

almohad6n de plumas?

Sleeping Beauty

El almohad6n de plumas

sh e

w ou ld

hav e

the

disposi tion of an angel; she

w as beautiful as an angel

she w ill fall into a deep sleep

that will last fo r a hund red

ye ars; she had had plenty of

ti me to dream of w hat she

w ould say to him; her good

fairy had made sure she had

sweet dreams during he r lon g

slee p .

rubia, angelical

fa iri es , s pells, mag ic ring,

pa lace

th en he arrive d a t a cou r tyard

tha t seemed like a p lace where

only fear live; an awful silence

filled it and the look of death

wa s on eve ry thi ng; he w ent

th rough a marble cour tyard .

sofiadas nmer ias; an tiguos

suenos: aun vivia dorm ida en

la cas a hostil; pronto Alici a come nz6 a tener al ucinaciones.

prod ucia una otona l impresi6n de palacio encantad o

La casa en q ue vivia influia no

poco en sus estremecimientos;

la b la nc ura del p ati o

silencioso - frisos, colu mnas y

es tatuas de marrnol: Den tro ,

el br illo glacia l del es tuco, sin

el mas leve rag uno en las alt as

pa redes , afirmaba aquella

sensaci6n de desapacible frio ;

espanto callad o.

26

Patricia Anne O dber de Baubeta

The reminiscences in the Quiroga text are not numerous, but

they are sufficient to act as signposts for th e read er, poi nting

him in one part icul ar d irection . One of these is tripling' 'the use

of the patterns of three as a formulaic p rincipl e'. See for

exa mp le, the firs t description of Ali cia, with thr ee adjectives

clustered together, " Rubia, an gelical, y tirnida" (p . 157). The

couple spe n d three m onths together befor e Alicia falls ill.

Qu iroga singles out three elements in th eir home, all de signed

to enhance o ur impression that Alici a is imprisoned in an

enc hanted pal ace - "frisos, columnas y es ta tuas de ma rrnol "

(p . 157). And th ere are othe r fea tures in com mo n, among th em

th e conscious use of a linear narr ative techni que", an d the

isolation of th e protagonist, defined by Max LUthi as "one of

the governi ng principles in the fa iry tale"" . El almohad6n de

plumas is narrat ed with total linearity, its tem poral progression

clearly delineat ed from the time of Alicia's ma rriage to Jordan

in April th rough three months of 'dicha especial', th e Autu mn

spent in "este extrano nido d e amor" (p. 157). Then th ere are

then the "dlas y di as" of Alicia's influe nza. It is as th ou gh

Qu iro ga wer e cold-bloo de dly marking off Alicia's last da ys on

a calendar, the last day she spends out of bed, th e following day

when the doctor is sum mone d . The read er th en accompan ies

Alicia through th e "cinco di as y cin co neches" it tak es for th e

monster - somew ha t rem iniscent of Poe's monster in Murder

in the Rue Morgue - to kill her. Quiroga 's narrative is almost

brutally spare - "Alicia muri6, p or fin" (p . 159). There are no

digressi on s o r supe rfluo us details, an d th is approach is quite in

keeping with the stylistics of the fai rytale, th e way in w h ich

characters are presented :

T heir p s y chol og ica l p ro ce s s es a re n ot

illuminated; on ly th eir line of progres s is in

focus, only that which is relevant to th e actionevery thing else is fade d out. They are b ound

neither to th eir surroundings nor to their past,

and no d epht of charac te r or p sych olo gic al

peculiarity is indicat ed . They are cut off from all

that - isolated".

Sleeping Beauty Meets.:

27

Sleepi ng Beauty could not be more isola ted, asleep in her castle

in the wood for a hund red yea rs. Alicia shares her physical

space with Jordan and a maid; but spends much of her time

asleep and could therefore be seen as liv ing in a self-im posed

isolation. If we look at other versions of the Sleeping Beauty,

Straparola's an d Basile's for instance, we find that the p rincess

is impregnated and conceives her children while she sleeps; this

violation s urely recall s th e mons tr ous insect penetrating

Alicia's body while she s leeps on her feat he r pill ow. In both

Sleeping Beauty and El almohad6n de plumas the re are forces at

work outside the lives of the female protagonists, either

supernatura l forces such as the fairies, or the monster that

drains Alicia's blood. The human beings w ho intervene in these

stories lack the p ower to act effectively on thei r ow n; w hen the

he ro ine is saved it is w he n the rescuer is backed up by

s uperna tura l forces . Fa iry- ta le h eroin es are not u sually

permitted any real contro l ove r their own destinies (at leas t, not

in Perrault). Perhaps this is why the voice of the heroine is so

rarely heard , why their speech is reported rather tha n di rect.

Alicia's voice is never hea rd in Elalmohad6n de plumas. Sleeping

Beauty's and Alicia 's lives are controlled an d circumscribed by

other people or forces : fairies, Jordan, the pa rasi te in the pill ow.

Both are dependent on others to rescue them from the

(fore-ordained) consequences of thei r actions and it see ms as if

the decisions that they make for themselves inevit abl y lead

them into the worst possible dan gers. In the case of Sleeping

Beauty, her problems arise when she tries to spin. Alicia's

problems, so it is implied, begi n with her marriage; she does

not have a good fairy to protect her, and Jord an hardl y qualifies

as a rescuing Pri nce". Wh en Alicia falls ill Jord an is unable to

save he r because he d oes not know what is causing her illness.

In fact, one of the 'minor ' shocks in this story is produced by

Jordan's response to the d octor on being informed that his wife

cannot be tr eated:

- [Solo eso me faltab a! - resopl 6 Jordan. Y

tambo rile6 bruscamente sobre la mesa (p. 158).

There have been othe r interpretations of Sleeping Beauty , so me

of which hav e interes ting implications for the way we read EI

28

Patricia An ne Odber de Baube ta

almohad6n de plumas. The seaso na l and solar theories explained

by Saintyves might account for the references to autumn and

co ld in Quiro ga's s to ry". But if w e ex ten d Bettelheim ' s

psychoanalytic interpretati on of Sleeping Beauty to Alicia, we

may a rrive at a so me w ha t d ifferent understanding of El

almohad6n de plumas:

Howev er gre a t th e va ria tions in d et ail, the

central th em e of all versi on s of The Sleeping

Beau ty is that, despite all atte mp ts on the pa rt of

pa r ent s to prev en t their ch il d's sex ua l

awa ken ing, it will take pl ace nonetheless 29•

Alicia is described in much the same wa y as we would expect

to find the traditional princess of European folklore, "rubia,

angelical y tfmida ". The accumulation ofthese ad jectives could

be taken as sy no ny mous with 'virgina l' . Perhaps ..ye are to

su p p ose that her marria ge h as been the rudest kind of

awa kening. The fa ilu re of the honeym oon, a "l argo esca lofrio",

and Alicia 's subseque nt unhappiness are due to Jordan 's sexual

demands on a shy, inex perience d girl:

El caracter d ur o de su ma rido hel6 sus sofiadas

ninertas de novia (p. 157).

Far from rescu ing Alicia , Jord an is the so urce of he r suffering ,

especia lly since he is not able to ve rbalize his love for her:

La amaba profunda ment e, sin darl o a conocer

(p . 157).

His reply to the doctor may be seen as the expression of his

feelings of exasperation tow ard s a wife whose illn ess will ma ke

it impossible for him to satisfy his sexua l d esires. Alicia is

frig htened, beset by "terrores cre p usc ulares" (p, 158), perhaps

because of her yo uth, or because she is sex ually frigid. She

th ere fore becomes an inva lid , " nega ndose a l mund o y

refu giada en su enfer meda d'r'", but th is does not save her. The

'monster ' continues to pen et rate her body until she finall y d ies.

The fairy tal e intertex t ca n nud ge th e reade r in one

interp retative direction; the va m pire intertext ma y send him off

in the opposite one :

Sleeping Beauty Meets...

29

Ta l monstruo apenas si es una ob jetivaci6n

fantasmal del verdadero del cue nto: el pr opio

Jorda n".

As w e read El almohad6n de plumas, w e are aware of the

interte xtual d ynamic between the v am p ire legend and

Quiroga's story. If, on the one hand, the fair y tale intertext hints

at what mi ght have transpired between Alicia and Jordan, the

va mpire component undermines this vision : it foreshadows

Alicia's s uffering and intensifies the horror of her death. It

might eve n p oint to the true nature of the relati onship between

Alicia and Jordan. We sho uld not underestimate the importance

of the go thic horror and the vampire motifs in El almohad6n de

plumas. Quiroga 's interes t in writers su ch as Hawthorne, Poe,

Maupassant, Merimee (au thor of Le Guzla, 1825 or 1826, whose

hero is a vampire), has been well-documented by a series of

critics, among them Margo Glantz in her discussion of ' Poe en

Quiroga ':

El almohad6n de plumas es un caso lipico de

vamr,irismo con la presencia de monstruo y

todo ' .

Pe ter Beardsell proposes a different reading, which would

confirm the proposition that the intertext can change the

meaning of the text:

Q ui r oga was d eliberately e nc ou r a gi n g his

readers to spo t the va m pire-like qu aliti es of thi s

story in orde r to mislead them and in crease th e

shoc k at the end 33.

Whether or not we agree with this theory, it seems fairly evident

that the va mpi re elemen t plays an important role, both in the

text and the intertext.

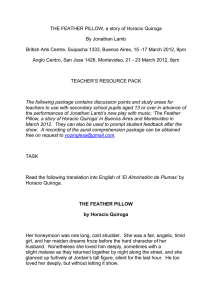

Ther e is another way to read El almohad6n de plumas: Alicia

is in love with Jordan, marries h im, but find s her relationship

sex ua lly unsati sfying . H ow do we arrive at thi s reading? By

comparing passag es from Stok er's Dracula with EI almohad6n de

plumas in orde r to establish possible corresponde ncesj", then

explori ng the implicat ions of this relationship .

30

Patricia Anne Odber de Baubeta

Extracts from Bram Stoker's

Dracula .

£1almohadon de plumas

Luc y Westenra 's Diary :

Hill ingham, 24 Augusto ...but

I am full of v ague fear, and I

feel so weak and worn out.

When Arthur came to lunch

he looked quite gri eved when

he saw me, and I hadn't the

s p iri t to b e cheerful. 25

August.

Another

bad

night.. .More bad dreams . I

wish I could reme mber them.

This morning I am horribly

weak. My face is ghastly pale,

and my throat pains me . It

must be s o m e th in g wrong

with my lungs, for I don't

seem ever to get air enough.

Letterfrom Dr.Seward to arthur

Holmwood: She com plains of

d iffi cu lty in breathing

satisfactorily at times, and of

heavy, lethargic sleep, w ith

dreams that frighten her, but

regarding which she ca n

remember nothing. (...) She

was ghastly, chalkily pale; th e

red seemed to have gone even

from her lips and gums, and

the bones of her face stood out

prominently; h er breathing

was painful to see or hear. (...)

There on th e bed, seemingly

in a swoon, lay poor Lu cy,

more horribl y white and

wan-looking than ever.

Al dia s ig u ien te amanecio

desvanecida. EI medico de

Jordan la examin6 con suma

atenci6n, ordenandola cam a y

descanso absoluto . (...) Alicia

no tuvo mas desmayos, pero

se iba visiblemente a la

muerte . (.. .) Pronto Alicia

comenz6

a

tener

al ucinaciones, confusas y

flotantes al principio. (...) Al

rato abri6 la bo ca para gritar,

y sus narices y labios se

perla ron de sudor. ( ... )

Durante el d ia no avanzaba su

enfermedad, p ero ca d a

manana amanecia livida, en

sincop e casi. Parecia qu e

iinicamente de noche se le

fuera la vida en nuevas

oleadas de sangre . Tenia

s ie m p r e al despertar la

sensaci6n

de

estar

desplomada en la cama con

un mill6n de kilos encim a.

Desde el tercer dia este

hundimiento no la abandon6

mas . (... ) Sus terrores

crepusculares avanzaban

ahora en forma de monstruos

que se arrastraban hasta la

cama,

y

trepaban

dificultosamente por la

colcha. (...)

Sleeping Beauly Meels...

31

Although it would be an exa ggeration to spe ak about

textual citations , there ar e surely correlati ons be tween Dracula

and certai n passages in El almohad6n de plumas. Lucy and

Alicia's sy mp toms are v irtually id entical , ev en if th eir

sufferings are caused by d ifferent creatures. It may be, as

Bea rd sell has argued, that Quiroga wishes to mislead his

reader s in order to shock them all the more when they reach the

en d of the sto ry. In any case, it is qu ite obviou s that Quiroga is

inco rporating gothic features in his story in order to achieve his

d esired 'effect':

In Gothic writi ng the reader is held in sus pe nse

with th e charac ters and increas ing ly th ere is an

effort to shock, alarm, and otherwise rouse him.

Ind ucing a powerful emotional response in the

read er (rathe r than a moral or intellectual one)

was the prime object of these novelists" .

The presence of gothic elements in El almohad6n de plumas is

undeniable:

'Gothic' fiction is the fictio n of the h aunted

cas tle, of heroines pr eyed on by unspeakable

terrors, of the bla ckly low er ing villain, of ghost s,

vampires, monst ers and werewolves" .

Alicia lives in a hou se which see ms to ha ve so me of the

cha racteristics of a castle '", she suffers all manner of fear 'estremecimientos', 'es pan to callado', 'te rrores crepusc ulares' .

Jordan answers in pa rt the description of 'blac kly lowering

villain', and the story contains a monster, if not a vampire. As

the nex t stage in this d iscussion, we sh ould perhaps cons ider

just what the va mpire represents in literary term s. David

Pu nter establishes a connec tion between the vampire with

d ream:

Both are night phen om ena whic h fade in the light

of day, both ar e considered in mytholog ical

sys te ms t o b e phys icall y w eakening, both

pro mise - a n d p erhaps d eli v er - an

unthin kable pleasure which cannot sustain the

32

Patricia Anne Odber de Baubeta

touch of reality. Also the vampire, like the

dream, can provide a representation of sexual

liberation in extremis, indulgence to the point of

death",

EI almohadon de plumas contains several references to dreams

and physical weakness, in addition to the allusions to monsters

and thedraining of blood. Perhaps the underlying suggestion is

that Alicia, far from being the frightened vic tim of a predatory

husband is herself the predator, unsatisfied and frustrated in

her marital relationship, and Margo GIants is right when she

suggests that:

Jordan se transfiere a un monstruoso insecto y la

delectacion erotica que su mujer no encuentra en

la vida cotidiana se transfiere igualmente al acto

de succion".

Emir Rodriguez Monegal supports this interpretation:

Una version completamente distinta a la

a necd o ti ca es tambi en posible : en la

impasibilidad y lejania del marido cabe ver el

motivo de los delirios eroticos de la mujer .

Quiroga introduce un monstruoso insecto para

no decir que el ser que ha vaciado a esta muj er es

el marido: con su monstruosa indiferencia ha

secado las fuentes de la vida . Serra este un caso

de vampirismo al reves",

Those readers familiar with Dracula will remember that when

Lucy Westenra is about to die (or be come one of the un-dead),

she undergoes a change of personality. No longer a 'model of

feminility and passivity", Lucy seems to undergone a loss of

purity and innocenc e, be coming instead sensual and

passionate:

Her breathing grew s te rto ro u s, the mouth

opened, and the pale gums, drawn back, made

the teeth look longer and sharper than ever. In a

sort of sleep-waking, vague, unconscious way

she opened her eyes, which were now dull and

Sleeping Beauty Meets...

33

hard at once, and said in a soft voluptuous voice,

such as I had neve r h ea rd from he r li p s :

- Arth ur! Oh, my love, I am so glad you have

come! Kiss me!"

Since Alicia never speaks, we m ust necessarily rely on the

di sclosures of th e narra tor to ex p lai n he r feeli n gs and

behaviour, but because his information is not always complete,

the reader is left wondering why Alicia sho uld willingly collude

in her ow n death :

No quiso que Ie tocaran la carna , ni aunque Ie

arrelaran el almoha d6 n (p. 158).

It is on ly when we resort to the va mpire inter tex t that w e find

a possible exp lana tion: that Alicia welcom es the depred ati ons

of the monster, obtaining some profoundly sensual pleasure

from the experience of having her blood drain ed.

Quiroga's £1 almohad6n de plumas ma y speak to us in

seve ral ways. It may strike us as a fairy tale tha t (contrary to

conventional rea de r expectations) goes ho rrib ly wrong and

ends in tragedy'3; we may rega rd it as a horror story in the

manner of Poe and others, and it may rem ind us of Bram

Stoker's Dracula and other gothic sto ries wit h haunted heroines

a n d v a m p ir e s. Bu t manifes tly beyond dis p u te is th e

'effec tiveness' of EI almohad6n de plumas. The deliberately

dispassionate linear na rrative, when combi ned w ith is multiple

intertexts, somehow succee ds in manipulatin g the rea de r's

response through a ga m ut of reaction s ra ng ing from curiosity

and puzzlement to shock an d revulsio n . The one emotion not

inspired by th is s tory is com passion, because Quiroga d id no t

wish to dilute the effects of his writing w ith surp lus emo tions

or sen time nts .

Notas

Ruben Cutelo. "Ho racia Quiroga: Vida y Obra", Capitulo Oriental 17.

l.A historic de la literatu re uruguaya, Montevideo , 1968, P: 263.

z

Jose E. Etcheverry, "Et ai nJolwd6n deplumas. La ret6rica del almohad6n",

in Aproximaciones a Horacia Quiroga, edited by Angel Flores, Caracas:

Mont e vila, 1976, p. 218.

34

Patricia Anne Odber de Baubeta

3

Alfred o Veirave, "EI almohad6n de plumas. Lo ficticio y 10 real ", in

Aproximaciones, p . 213: "La atm6sfera d e sombras parnasiana s en la qu e

esta envuelta la morte de Alicia ('rubia, angeli cal y timida'), coloca a la

protagon ista desde su apari ci6n en un marco de irrealidad y fantasia

firmemen te trazado".

4

Michael Riffaterre, "Toward s a Formal Approach to Literary History",

in Text Production, translated by Terese Lyons, New York: Columbia

University Press, 1983, p. 99.

5

One of the most recent commentaries on Elalmolrad6n de plumas appears

in Peter Beardsell's Critical Guide, Quiroga. Cuentos de amorde locura y

de muerte, London: Grant&Cutler, 1986. Maria E.Rodes de Clerico and

Ram6n Bordolo Dolci published a detailed textual analysis of El

almohad6n de plumas, in Horacio Quiroga. Antologfa y estudio critica,

Montevideo: Area, 1977, pp. 37-54.

6

Michael Riffaterre, "Syllepsis", Critical Inquiry, VI, n04 (1980), p. 626.

See Worton and Still's comment in their introduction to Intertextuality:

Theory and Practices, Manchester and New York: Manchester University

Press, 1990, P: 1: "The writer is a reader of texts (in the broadest sense)

before s/he is a creator of texts, and therefore the work of art is

inevitably shot through w ith references, quotations and influences of

every kind".

7

Michael Riffaterre, "Comp u lsory Reader Response: The Intertextual

Drive", in Worton and Still, p. 57.

8

Laurent Jenny, "La Strategie de la forme", Poetique, 27 (1976), p. 279.

9

Quiroga himself describes EI almohadon deplumas as a 'cu ento de efecto',

in his letter to Jose Maria Delgado of 8 June 1917: "Un buen d ia me he

convencido de que el efecto no deja de ser efecto (salvo cuan da la

historia 10 pide), y que es bastante mas dificil met er un final que ellector

ha ad ivinado ya" (Cartas ineditas. VolumeII, Montevideo: lnstituto

Nacional de Investigaciones y Arch ivos Literarios, 1959, p. 62). For

Rodes de Clerico and Bordoli Dolci, the CIlento de eJecto "combina los

di stintos elementos y acaeceres teniendo en cu enta el efecto final que,

como resultado de un desencadamiento minucioso y eficaz, es rapido

y directo", op . cit., p. 54.

10

Emir Rodriguez Monegal, Genio y figura de Horacia Quiroga, Buenos

Aires : Eudeba, 1967, pp. 58-59: "EI supuesto toque cientifico final no

hace sino subrayar ir6nicamen te hasta que pun to Qu iroga esta tratando

temas suprareales".

11

Margo Glantz, "Poe en QUiroga", in Aproximaciones, P: 107.

12

See Ell iott B.J. Gose, Imagination indulged: The Irrational in tire

Nineteenth-Century Novel, Montrea l and London: McGill-Queens

University Press, 1972, p. 42: "Like the gothic novel, the fairy tale often

deals in adventures that are literally impossible in the actual world,

Sleeping Beauty Meets...

35

and manages quite well with a setting remote from the experience of

its readers. Because they share so many of th e characteristics attributed

to romance by Chase, both the fairy tale and the gothic novel require

Colerid ge's romantic so spension of d isbelief". There is a general

agre ement that Sleeping Beallty is a literary work, taken not from

folklore but from ear lier literary sources. Perrault first published La

Belle au bois dormant in February 1696 in LeMercuregalant, and several

scholars (for instance, P.Saintyves, Les Contes de Perrault et les rtcits

parallele», Paris: Librai rie Critique, 1923), have revealed how it is based

on earlier tales. Jacques Barchilon maintains that Perrault's tales are

part of the literary canon, in Le con te meroeilleuxfrancai« de 1690a1790,

Paris: Honore Champion, 1975, p . 27: "Le conte de fees es un art

d ' imagination, un art dont le secret est sa profonde resonance

psychologique: les personnages de Perrault ne cesseront jamais de faire

rever. II suffit d'enumerer la liste prestigieuse des personnages de

Perrault pour cons tater que sa Belle au bois dormant, sa Cendrillon (...)

appartiennent acette vivante galerie des personnages de tous les temps

et tous les pays, au x cotes de Don Qu ichotte, Don Juan, Hamlet ou

Faust". The Grimm ve rs ion of the same fairy tale, Domoroschen, is

equally 'literary', owing little to peasant lore .

13

We should not discount the impact of two other elements that feed into

our intertext, firstly the ballet Sleeping Beauty, and secondly Disney's

cinematographic production of 1959. Ballet and film may be as much a

part of the intertext as a novel, poem or play. See, for example, Keith

A.Reader's art icle on filmic intertextuality, Literature /cinema /

television: intertextuality in Jean Renoir's Le Testament du Docieur

Cordelier, in Worton and Still, pp. 176-189.

14

See Jacques Barch ilon 's remarks, op. cit., P: 27: " Des millions de

lecteurs ou d 'auditeurs de tous ages et de tout acabit ont fait une place

aux personnages de Perrault dans leur mythologie personelle". Ruth

B.Bottigheimer makes an extremely valid point in her book Grimm's

Bad Girls and Bold Boys. The Moral and Social Vision of the Tales, New

Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1987, P: 35, when she points

out: "Differen t social or geographical environments harbor vastly

different social views and tend to amend popular tales in accordance

with familiar so cial codes. Basile's Pentamerone and Perrault's Contes

both retain the same or very similar constituents to tell a Cinderella

story, but motivations and outcomes differ profoundly from the

Grimm's version, illustrating quite neatly how contemporary mores,

audience expectations, narrative voice, and authorial intentions color

tale elements". This kind of difference is arrestingly exemplified when

we compare Basile's Sun, Moon and Talia with La Belle au bois dormant

and read that in the former, the King does not wait for Talia to awaken

before making love to her, fathers two children, then forgets all about

her for the next nine months. As far as the importance of the happy

36

Patricia Anne Odber d e Baubeta

en ding is concerned, see Brun o Bettelheim's discussion of the ha pp y

en ding as a feature o f the fairy tale, in The Uses of Enchantment,

Harmondsw orth: Penguin, 1978, p230: "The happy end ing requires

that the evil principle be appropriately punished and done awa y with;

only then can the good, and with it happiness, prevail. In Perrault, as

in Basile, the evil principle is done away with, and thus fairy-story

justice is done". This is linked to the in vulnerability of characters, wh o

escape from danger at the last minute. Heroines (with the exception of

Little Red Riding Hood), are always rescued (Barchilon, op. cit., p . 29).

Citing J. R.R.Tolkien, Bettelheim writes: "Tolkien describes the facets

wh ich are necessary in a good fairy tale as fantasy, recovery, escape,

and consolation - recovery from deep de spair, escape from some great

danger, but, most of all, conso lation. Speaking of the happy ending,

Tolkien stresses that all complete fairy stories must have it" (T ree and

Leaf. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1964, pp . 50-61, cited on

p. 143). Bettelheim then con tinues: "Maybe it would be appropriate to

add on e more element to the four Tolk ien enumerates . I believe that an

elem ent of threat is crucial to the fairy tale - a threat to the hero's

physical existence o r to his moral esi stence" (p. 144).

15

See John frow, "lntertextuality and Ontology" in Worton -and Still,

p. 46: "Intertextual analysis is distinguished from source criticism both

by this stress on interpretation rather than on the establishment of

particular facts , and by its rejection o f a unilinear casuality (the concept

of 'influence') in favour of an account of the w ork performed o n

interte xtual material and its functional integrati on in the later text ".

16

See Jose Luis Martfnez Morales, Horacia Quiroga: Teoria y practica del

cuento, Xalapa : Uni versida d Veracruzana, 1982, p. 76: "No hay que

olvida r que el exito de la producci6n y difu si6n del cuento liter ario

finca sus ba ses en el stglo diecinueve par la difusi6n y recopilaci6n de

los cuentos popularee". Compare QUirog a's comments on the short

story with those of Jacques Barchilon, op. cit., p. XV: "Le conteur de

fiction s merveill euses, qui di spose d'un espace plus bref que le

romancier pour cap tive r so n lecteur, doit Interesser vite et bien . 5'H

n'krit pas av ec esprit et concis ion, Hie perd ", Qu iroga writes, in "La

crisis del cu en to naci onal ", in Sabre literatura . TomoVII. Obras ineditas y

desconocidas, Montevideo : Area, 1970, pp . 92-96 : "EIcuentista nace y se

ha ce. Sin innat as en ~ I la energta y la brevedad de la exp resi6n; y

ad quiere con el tran scu rso del tiem po la habilidad para sa car el ma yor

partido posible de ella en la composid6n de sus cuentos (...) EIcuenti sta

tiene la cap acidad d e sugerir ma s que 10 que dice. EI nov eli sta, para un

efeeto igual, requiere mucho mas es pecio" . In "La ret6rica del cuen to",

loc.cit., Qui roga reit erates his view s: " El cuento literano (...) cons ta de

los mism os elemen tos sucintos que el cuento oral, y es com o este el

re lato de una historia bastante interesa nte y suficienteme nte breve para

que absorba toda nu estra atencion", Quiroga's story is designe d to

Sleeping Beauty Meets ...

37

insp ire fear in the reader, ando so, in many cases, is the fairy tale. See

also Tzvetan Todorov , The Fantastic. A Structu ralApproach to a Literary

Genre, tranlated by Richard Howard, Cleveland and London: The Press

of Case Western Reserve Un iversity, 1973, p. 35: " Fea r often linked to

the fantasti c" ,

17

18

See Quiroga's comme nt in La ret6rica del cuento, pp. 115-116: " Los

cuen tos ch inos y persas, los grecolati nos, los arabes de las Mil y una

naches, los del Renaci mie nto italiano, los de Perrault, de Hoffm ann, de

Poe, de Merimee, de Bret Harte, de Verga, de Chekov, de Maupassan t,

de Kipling, tod os ellos son una so la y misma cosa en su rea lizaci6n.

Pueden di feren ciarse un os d e otros como el sol y la luna . Pero el

conce p to, el coraje para con tar, la in tensidad, la breved ad, son los

mismos en todas los cuentistas d e todas las edades". Qui roga

published a short story en titled La Bella y 10 Bestia in the collec tion EI

rna alla. Th e sto ry has nothing to do with th e original fairy tale and the

title is used as an ironic comment on the fem ale p rot agon ist (heroine).

There are also the stori es that Quiroga wrote specifically for chi ldre n,

Cuentos de 10 selva. Ad d it ionally, we migh t also take note of Alfred

Melon 's obse rva tio ns in his article " Reflexion s sur les a rnbigui tes

constituti ves d u con te latino-arner ica in mod erne", in Techniques

narratives et representatives du monde dans le conte Iatino-americain.

America. Cahiers du Criccal. nOZ, 2eme semestre, 1986. Universite d e la

Sorbonne Nou velle Pari s III, p. 56: "De la m eme maniere, s'il est evide nt

qu e les co ntes de Quiroga (...) sont etrangers aux struc tures cod ifiees

de la litterature d e trad ition or ale, strictu sensu; s'Il est certain qu 'aucun

de leu rs recits ne pourrait etre raconte, transmis oralement, a lte re d ans

les aleas de sa transmi ssion (com me Ie romance, par exemp le, ou Ie

con te creole), iI n'empeche que Ie lecteu r reconn ait des croyances, d es

legendes, les aphorismes, les s im ula tio ns rituelles, les rnod eles

arche typi ques de la tradi tion populaire (...) qui cree nt I'illusion de

re constitutions p on ctuelles d es tra ces d 'une Iitter atur e o ra le " .

Fernando Ainsa see ms to share this feeling th at a wh ole series of

elements feed into Qui rog a' s work in his study "La estr uctu ra abierta

del cue n to lat in oam er ica no ", pp . 69-70 of the sam e journal: "La

recuper aci6n a traves d e nuevas formulaciones esteticas, de las rakes

an teriores d el cue ntc, tales como la oralidad, el imagina rio pop ular y

colectivo pr esente en mi tos y tradiciones y las formes arcaicas de

sub-ge ne ros que estaba n en el orfgen del ge nera (pa rabolas, Cr6n icas,

Baladas leyendas, 'ca ractc res'. etc.), la mayorta de las cua les no hab ian

ten ido e n su mom enta h ist6rico una exp resi6n a mericana . En es ta

d eliberada recupera ci6n se recrean formas y se reactu aliza 10 mejor de

generos ya olvida dos",

Accordi ng to Todorov , op. cit., p. 83: " It is no accident that tales of the

marvelous rerely employ the first per son (...). They have no need of it;

their superna tu ra l un iverse is not intended to awaken doub ts".

38

Patricia Anne Odber de Baubeta

19

All quotation are taken from Cllentos Completos. Volumen 2, second

edition, Montevid eo: Ediciones de la Pla za, 1987, pp. 157-159.

20

See Michael Riffat erre's expl anation of in ter textuality, in "Co mp ulsory

Reader Response ", p. 76: " In tertextuality enables the text to represent,

at one and the same tim e, the following pair s of opposites (within each

of which the first item corresp onds to the int ertext): convention an d

departures from it, tradition and no ve lty, sociolec t and idiolec t, the

already said and its negation or tr ansform ation".

21

Marc Eidgelinger, Mythologie et intertextualite, Geneva: Slatkine, 1987,

pp. 12-13.

22

TheFairy Tales of Charles Perrault, transla ted by Angela Carter, London:

Victor Gollane z, 1977, pp. 55-71. The Brothers Grimm. Papillar Folk Tales,

transla ted by Brian Ald erson, London : Victor Gollancz, 1978, pp. 39-42.

See also Max Luthi's stylisti c comparison of the tw o ver sions, in The

Fairytale as Art Form and Portrait of Man, translated by Jon Erickso n,

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984, pp. 60-61.

23

Max Luthi, op . cit., p. 170.

24

Max Luthi, op. cit., P: 40: " Both the representat ional and narr a tive

techniques of the European fairy tal e, in particular, tend to be lin ear.

Objects and figures a re seen as linear shapes, and the development o f

the plot and the ordering of episodes, sentences, and words can also be

called linear".

25

Max Luthi, op. cit., p. 42.

26

Max Luthi, op. ci t., P: 42-43.

27

See Ruth B. Rottigh eimer's comment in her chap ter "Tow ers, For est s,

and Trees" , op. cit ., p. 101: "The s ing le most pervasive ima ge evoked

in the popular mind by the word fairy tale is probabl y that of a maiden

in di stress leaning from a tower w indow an d sea rch ing the horizon for

a rescu er ".

28

P. Saintyves, pp. 71-101.

29

Bruno Bettelheim, op . cit., p . 230.

30

Alfredo Veirav e, op. ci t., p. 213.

31

Jose E.Etcheverry, op. cit., p . 217.

32

Margo Glantz, op. cit., p. 104. Gla ntz goes on to point out a furth er

di me nsion to th e story: "antes gu e nada es el pl anteamiento d e esa

sinr az6n, de ese caos que d ebe legit imarse en Crases explicativas y

sere nas, en el q ue dos seres hu ma nos se ama n, pero se dest ru yen ".

33

Beardsell, op. cit., p. 39.

34

For Mar go Glan tz, th ere is no quest ion about QUirog a's use of th e

vampi re the me, op . cit., pp. 104·105: " La heren cia es cla ra en Q ui roga.

Sleeping Beauty Meets...

39

Lo im po rtante no es detec tarla porq ue a fue rza de ex istir es ob v ia, sin o

definir su sentido" .

35 Robert D. H urne, "Go thic versus Romantic", Publications of the Modern

Langll.ge Associ, 'ion , 84 (1969), pp. 282-290.

36 Davi d Pun ter, Tilt Literature of Gothic Fictions fro m 1765 to th e Present

Day, London : Lon gm ann, 1980, p. I.

37

Rodes de Clerico a nd Bordoli Dolci, op. cit., p. 42: " La casa tiene algo

de ad us ta mansi6n que la aprox ima - aunque lejanamente - a la

atm6sfera g6tica ex istente en los cue ntos de E.A.Poe" .

38

Davi d Punt er, op. cit., pp. 118·119 .

39

Mar go Glan tz, o p. cit., P: 106.

Mon egal, El deste rmdo . Vida y obrade Horacia Quiroga,

Bueno s Aires: Losada, 1968, p. 116.

40 Emi r Rodriguez

41

David Pu nter, o p. cit., p . 262.

42 Dracula,

P: 147 .

43 See Max Luthi's views o n the us ual endings o f fairy tales , o p. ci t.,

pp.56-57.

Anuncio

Documentos relacionados

Descargar

Anuncio

Añadir este documento a la recogida (s)

Puede agregar este documento a su colección de estudio (s)

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizadosAñadir a este documento guardado

Puede agregar este documento a su lista guardada

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizados