Farmworker Protections and Labor Conditions in Brazil`s Coffee Sector

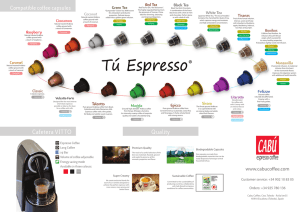

Anuncio