E-Prints Complutense - Universidad Complutense de Madrid

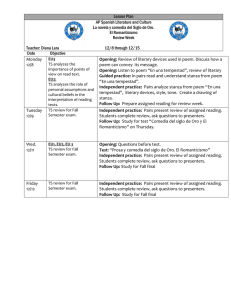

Anuncio