Austen, Jane ``Sense and Sensibilidad`

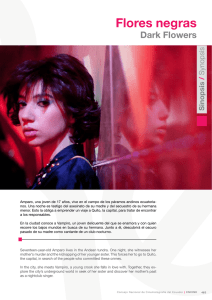

Anuncio