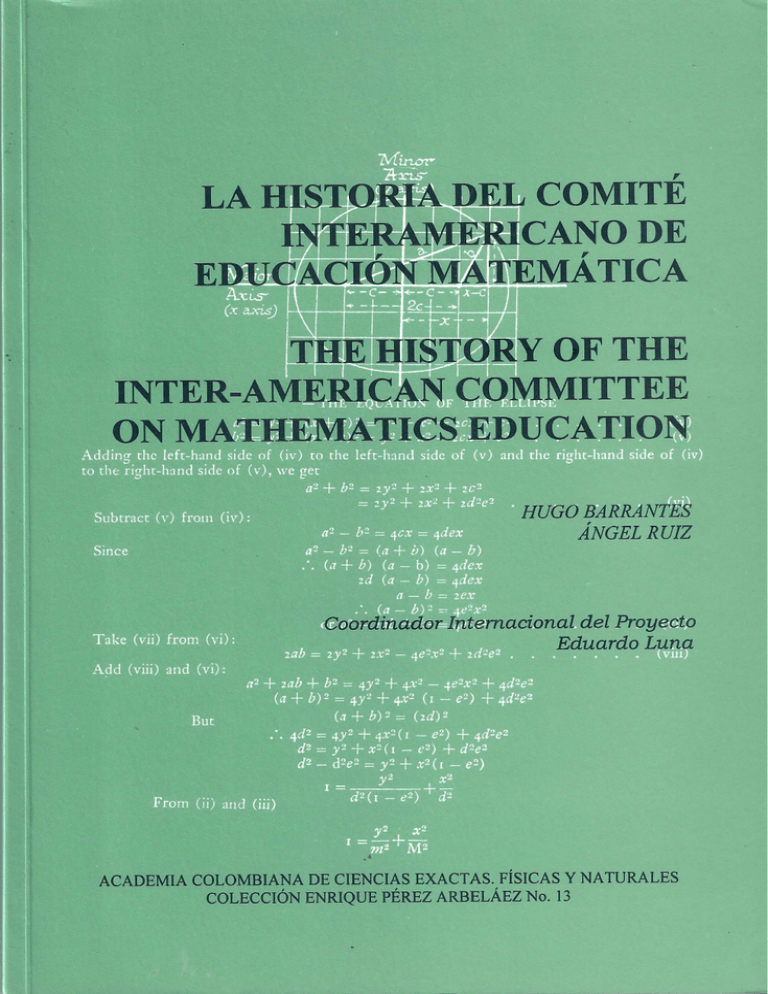

La Historia del Comité Interamericano de Educación Matemática

Anuncio