Modified Human Skulls from the Urban Sector of the Pyramids of

Anuncio

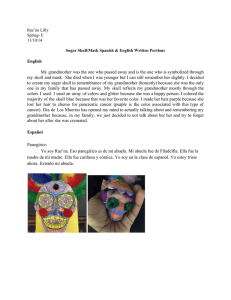

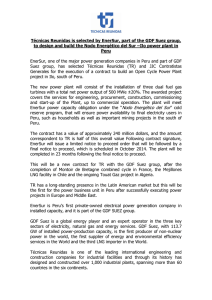

MODli'lED HUMANSKULLSFROM'1'"EURBANSECTOROF'1'"E PYRAMIDSOF MOCHE,NORA1'"ERN PERU JohnW. Verano,SantiagoUceda, Claude Chapdelaine,RicardoTello, MariaIsabel Paredes,and Victor Pimentel Recent excavations in the urban sector of the Pyramids at Moche in northerncoastal Peru exposed two modified humanskulls that were placed in an adobe niche within a domestic structure I00 m west of the Pyramid of the Moon ca. A.D. 400-650. A portion of the cranial vault is cut awayfrom the top of each skull, and one shows drilled holes for attachmentof the mandible. The skulls show a close resemblance to certain Moche ceramic skulljars that have a similar opening at the top of the vessel. Osteological analysis indicates that both skulls are of young adult males. Cut marks on the external surfaces of the cranial vault,face, and mandible indicate that they were preparedfromfleshed heads and not from dry skulls. Thefinds at Moche are thefirst documentedexamples of thisform of cranial modification, although an early Spanish account describes a similar trophy vessel that belonged to the lnka Atahualpa. Comparisonof the Moche modifiedskulls with Nasca trophyheads reveals that the two were prepared and leseddifJ7erently. En excavaciones recientesen el sector urbanodel sitio de las Piramidesde Moche en la costa norte del Peru'se descubrierondos cra'neoshumanosmodificadosque habian sido colocados en un nicho de adobe, dentrode una estructuradome'sticaa I00 m al oeste de la Piramidede la Luna ca. 400-650 d.C. En cada caso, unaporcion de la bo'vedacraneanafue removida,y una de ellas muestraperforacioneshechaspara articular la mandfbula.Ambospresentanuna gran semejanzacon cera'micaMoche enforma de craneo, que tienen aberturassimilares en su parte superior.El analisis osteolo'gicoindica que estos craneos pertenecierona varonesadultosjovenes. Ambospresentanmarcas de corte en las superficiesexternasde la bo'vedacraneal, la cara y mandibula realizadasduranteel proceso de descarnamiento,lo cual indica quefueron preparadosa partir de cabezas, y no a partir de cra'neos ya secos. Estos hallazgos en Moche so1 los primernsejemplos documentadosde este tipo de modificacio'ncraneal, aunque un reporteespanol tempranomenciona una vasija trofeo semejanteque pertenecio al Inca Atahualpa.La comparacionde estos craneos modificadosMoche con las cabezas-trofeoNasca revela diferencias significativas tanto en el me'todode preparacio'n, como en su posible funcio'n. Burials of isolatedhumanskullsandmummified heads have been reportedfrom a number of Andeanarchaeologicalsites (Verano 1995). Some of these for example at Chavin de Huantar(Burger 1984:31), Huari (Brewster-Wray 1983),andPikillacta(McEwan1987:39) appearto representthe secondaryreburialof humanremains as dedicatoryofferingsin architectura]features.In othercases,however,mummifiedheadsandisolated skulls show clear evidence of intentionaldecapitation and perimortemmodification,suggesting that headsweretakenfromcaptivesor sacrificialvictims as trophiesor ritualobjects.Ethnohistoricaccounts andiconographicdepictionssuggestthatthe collection andmodificationof humanheadswas a temporally and geographically widespread practice in SouthAmerica(Browneet al. 1993; Cordy-Collins 1992; Proulx 1971, 1989;Verano1995). However, osteologicalevidenceof decapitationandmodification of humanheads is relativelyrarein the archaeologicalrecord,withtheexceptionof thewell-known mummifiedtrophyheads of the Nasca culture of southerncoastal Peru (Browneet al. 1993; Verano 1995). John W. Verano * Departmentof Anthropology7Tulane University, 1021 Audubon Street, New Orleans, LA 701 18, USA Santiago Uceda * Facultadde Ciencias Sociales, UniversidadNacional de Trujillo, CiudadUniversitaria,Avenida Juan Pablo II s/n, Trujillo, Peru Claude Chapdelaine * Departementd'anthropologie, Universite de Montreal,C.P. 6128, succursale Centre- ville, Montreal, Quebec H3C 3J7, Canada Ricardo Tello, Maria Isabel Paredes, and Victor Pimentel * Proyecto Arqueologico Huaca de la Luna, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Jr. Junin 682, Trujillo, Peru LatinAmencan Antiquity,10(1), 1999, pp. 59-70 Copyright(C)1999 by the Society for AmericanArchaeology 59 This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions - 60 AMERICANANTIQUITY LATIN 10, No. 1, 1999] [Vol. J Areaof Mocheocc j abon History). of DonaldMcClelland,FowlerMuseumof Cultural Figure1. Map of the northcoast of Peru (Courtesy of a In this report,we presentthe first evidence a new and distinctiveform of "trophy"skull from on majorMocheceremonialandresidentialcomplex showskulls two describe We Peru. thenorthcoastof modifiing evidenceof perimortemdefleshingand vessels ceramic Moche Although cationintovessels. arethe these known, are skulls in the formof human Cut skulls. human actual from firstexamplescreated indicate skulls the of surfaces markson the external prethat they were preparedfrom fleshed heads, vicsumablyfrombattlefieldcasualtiesorsacrificial disand tims.Scenesdepictingthecapture,sacrifice, Moche in known membermentof prisonersarewell Thisdiscoveryprovidesadditionaleviiconography. denceto supporttheargumentthatMochedepictions of prisonercaptureandsacrificereflectactualevents, Donnot simply mythologicalnarrative(Alva and and Donnan nan 1993; Bourget 1997a, 1997b; Castillo 1994). in The two modified humanskulls were found This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions REPORTS 61 Figure 2. Location of ZUM Sector 8 (modified after Shimada 1994: Figure 2.1). July 1996 during excavationsin a room complex located approximately100 m west of the Pyramid of the Moon at the site of the Pyramidsat Moche in northerncoastalPeru (Figure1). Excavationof the complex, designated ZUM 8, was supervised by RicardoTellounderthe auspicesof theZonaUrbana Moche (ZUM) Project. John Verano and Laurel Andersonof TulaneUniversityexposedandremoved the skulls, which were subsequentlyreconstructed and analyzed by Verano at the Archaeological Museum of the National University of Trujillo. Archaeologists Maria Isabel Paredes and Victor Pimentelanalyzedthe associatedceramics. The Proyecto Zona UrbanaMoche was establishedin 1995 as a long-termstudyof the urbansec- tor of the Pyramidsat Moche (Uceda et al. 1997). The projectinvolvesresearchersand studentsfrom theUniversityof MontrealandtheUniversityof Trujillo, andoperatesunderthe auspicesof theProyecto Huaca de La Luna, codirectedby SantiagoUceda and RicardoMorales of the Departmentof Social SciencesattheNationalUniversityof Trujillo(Uceda andMorales1993,1994, 1996). Overthe pastthree years,surfacesurveyandexcavationof theurbansectoratMochehasrevealednew informationaboutthe site-identifying residential complexes, artisan workshops, storage areas, streets, and plazas (Chapdelaine 1997)-that along with the monumentalPyramidsof the SunandMoonconstitutethe urbancore of the site (Uceda et al. 1997). This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions LATINAMERICANANTIQUITY 62 [Vol. 10, No 1, 19991 - L_< -L .EL I I | O M 1 Figure 3. Plan of ZUM 8. Arrow at bottom left indicates the niche where the skulls were found. The skullswere foundin UrbanSector8 (Figure to thewest by a canalthatcutsthroughvariousarchi2), on the west side of a platformexcavatedby Max tecturalunits leading to a ceramicproductionarea IJhlein thelatenineteenthcenturydesignatedSite"F' southof ZUM 8, andto theeastby a patiowithraised (Kroeber1925;Uhle 1915).Recentexcavationsreveal benchesthatforms a cornerwith Uhle's Site F. The skullswere foundin one of five niches built ZUM 8 to be aneliteresidentialareawithatleastfour distinctconstructionphases. The room complex in within the southernwall of a residentialstructure which the skulls were found, which correspondsto locatedin thecenterof ZUM 8. Thenichesarequadthe secondconstructionphase,is L-shaped,approxi- rangularin form,approximately60 cm to a side,with mately25 x 20 m in maximumdimensions,with its access from above. Four of the niches were filled long armorientedN-NE/S-SE(Figure3). The com- with clean sand.The niche with the skulls, in conplex is composedof a seriesof roomsandpatioswith trast,was filled with a compactsedimentcontaining raisedbenchesconstructedof adobewith clay-plas- fragmentsof pottery,charcoal,the completescapula found of a camelid,and variousfragmentsof animalbone teredwallsandfloors.A charcoalconcentration in associationwitharaisedbenchin thesouthernpatio (Figure4). The natureof the niche fill (fragmentsof (CuadroC2, Unidad2, CapaC) builtduringthe sec- potteryandapparentdomesticrefuse)andthelackof ond constructionphaseyielded a dateof 1520 + 50 any apparentcarein placementor onentationof the B.P.(Beta-96033),witha 2 sigmacalibrationof A.D. skullssuggestsa ratherperfunctoryburial.The niche 43(K45. This datefits well withina seriesof radio- lays underan intactfloor correspondingto the third carbondatesfromMocheIV contextsin thecenterof constructionphaseof ZUM 8. A relativedate for the niche depositcan be estithe urbansector(Chapdelaine1997:75-79). The southernlimit of the complex is definedby mated from ceramicsrecoveredfrom the floors of a thick wall that extends eastwardto the principal the complex and withinthe niche itself. Diagnostic platformof the Pyramidof the Moon. It is delimited ceramicsherdsfoundon thefloorsof the secondcon- This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions REPORTS 63 Figure 4. Photographof the niche during excavation, showingSkull 1 (a), Skull 2 (b) and the camelidscapula (c). Skull 1 lies on its left side, with the mandiblearticulated.Skull 2, whichlacks a mandible,lies face down. structionphaseof ZUM 8 correspondstylisticallyto LarcoHoyle's MochePhaseIV (LarcoHoyle 1938, 1939).A totalof 27 ceramicfragmentswere recoveredfromthe niche. Of these,5 areportionsof vessel rims, 3 are fragmentsshowing decoration,and 19 arenondecoratedbody sherds.One of the decoratedfragmentsis partof a moldmadefigurineor musical instrument;the other two are small fragmentsof decoratedbottles.The rim fragmentsrepresent jars of several forms that are similar to domestic vessels found in other habitationalcomplexes between the two pyramids and resemble domestic vessels that Donnanhas describedfrom Moche sites in the Santa Valley (Donnan 1973:82 93). Soot on the externalsurfaceof one of thejarssuggestsuse as a cookingvessel,andtheinteriorsurfaceof theneckof one of thevesselshasthree obliquely orientedincised lines, probablymaker's marks(Donnan 1973:93 95). Figure5 a, b. Photographand drawingof Skull1. Crosshatchedareasin the drawingindicatemissingbones. Skull 1 Skull 1 consists of most of the left side of the vault (frontal,parietal,temporal,occipitalbones)andface (left zygomatic and maxilla), and most of the mandible(Figure5). The left maxillahas two teeth still present in their sockets: the canine and first molar.A lowercentralincisorwasfoundin thesocket of the left firstpremolar.All otheralveoli are filled Description of the Skulls with dirt, indicatingpostmortemloss of the correTechnicallyspeaking,the two "skulls' foundin the spondingteeth. nicheareincompletecrania, oneof whichhasanassoThe left half of the mandibleis completeexcept ciatedmandible.For simplicityof description,how- for minor breakageof the coronoid process and ever,theywill be referredto as Skull 1 andSkull2. condyle. About one-third of the right horizontal This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 64 LATINAMERICANANTIQUITY ramusis preserved,with breakageposteriorto the secondmolar.Thefollowingteetharepresentin their properalveoli:left canine( l/2 of crownmissing;old breakage),P3 , M2;right Il (root only; old breakage), P3 (root only; old breakage),P4, Ml, M2.The left first molarwas lost antemortem,and its socket is fullyresorbed.An upperleftthirdmolarwas found occupyingthe socket of the lower left thirdmolar. Its rootshadbeen modified(below) to allow it to fit into the socket. The morphologyof the socketsof the left upper andlowerthirdmolarsindicatethattheyhaderupted andwere in occlusion at the time of death.The single upperthirdmolartooth, if it indeedbelongs to this individual(below), shows bluntingand polishing of the cusps, indicatingthatit was in occlusion for some periodof time priorto death.Teethstill in properpositionshow wear consistentwith a young adult(ca.20 to 35 years),basedon attritionratesseen in other Moche skeletal samples (Verano1997a). Estimationof age on the basis of cranialsutureclosureis hardto evaluatedueto thefragmentary nature of the skull,butvisibleportionsof thecoronalsuture show no obliterationinternallyor externally.Morphology of the chin and size of the left mastoid processstronglysuggest male sex. Modificationsto Skull 1 includethe removalof a portion of the skull vault, the drilling of holes throughthe mandibleand temporalbone, filing of tooth roots, and cut marksindicativeof intentional defleshing. The top of the vault has a large oval defect, approximately103 mm in maximumdiameter at the level of the externaltable.The defect is beveled inward,such thatits maximumdiameterat the internaltableis 94 mm. The lateralmarginsare not preserved sufficiently to measure maximum diameterin the coronalplane,butit appearsthatthe openingwas slightlymorenarrowside to side than frontto back.The bone appearsto havebeen cut by repeatedgroovingwitha sharpinstrument. Although the defect is similar to trephineopenings seen in skulls from various central and southernAndean highlandsites, as well as some OldWorldexamples (e.g., Lisowski 1967), surgeryon a living patientis unlikely in this case, as there is no evidence that trephination waspracticedby theMocheorotherPrecolumbianculturesof the northcoast of Peru(Lastres andCabieses 1960;Verano1998a). The mandiblehas two holes drilledthroughthe leftascendingramusbelowthemandibular notchand [Vol. 10, No. 1,1999] Figure 6. Teeth with modified roots, Skull 1. onejustbelowthecondyle.All threeholesareapproximately4 mmin maximumdiameterandweredrilled fromthe outsidein, as theyareconicalin cross-section and largerin diameteron the external(lateral) surfaceof theramus.Twoholesalsoweredrilledverticallythroughthezygomaticprocessof thelefttemporalbone Presumably,cordswerepassedthrough theseholesto attachthemandibleto thecranium.The right temporalbone and ascending ramus of the mandibleare not preservedsbut presumablywere perforatedas well. A single hole also was drilled throughthemastoidprocessof thelefttemporalbone (Figure5). This hole does not seem to be relatedto the attachmentof the mandible;it may have served to hold an earornamentor otherobject. Four teeth show filed or cut roots (Figure 6). Apparentlytherootsweremodifiedso thattheycould enteran emptyalveolusandreplacea tooththathad been lost postmortem.Two of these (mentioned above)were foundin socketsto which they clearly did not belong, while two othermolarswere found loose in the niche fill. All teeth are pennanentand have occlusalwearcompatiblewith the seventeeth still in theirpropersockets.It is likely thatthe modified teeth are from this same individual,although they may have been obtainedfrom skulls of other individualsof similarage. This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions t: l: vs REPORTS tion of occipital,andrighttemporal)andportionsof the base of the skull are preserved,includingthe basioccipital,distalportionof thebasisphenoid,and the left occipital condyle. The right temporalwas brokenin a numberof pieces, but could be reconstructed,and it was found to have no perforations throughthe zygomaticarchor throughthe mastoid process. The left temporaIis less complete, but enoughof the zygomaticprocessis presentto indicate that no drilled holes are present.T}le face is fragmentedbut the maxillae and zygomatics are nearlycomplete,except for some of the thin bones of the nasal processesand the cheek area.The folSkull 2 lowingteetharepresentandin theirsockets:the left Skull2 is morecompletein somerespectsthanSkull canine, M1and M2; and the right M1 3. All other 1, althoughit lacks a mandible(Figure7). Most of socketsareemptyand show no alveolarresorption, the vaultbones(thefrontal,parietals,squamouspor- indicatingthatthe teethwere lost postmortem.The only tooth found loose was the right M3. Its roots | S2mm. + 76 mm. show no evidenceof modification. The spheno-occipital synchondrosis (basilar suture)is obliterated,suggestingan age of at least 20 years (McKern1970). Cusp wear on the upper molarsis similarto thatof Skull l, consistentwith anage atdeathof approximately20 to 30 years.Size of the rightmastoidprocessandzygomaticsandthe prominenceof GlabelIasuggestmale sex. Evidence of culturalmodificationof Skull 2 is limitedto removalof a portionof the vaultandcut markson variousbones. The vaultopeningis estimatedto havebeen approximately80 mm in maximumdiameter.Like Skull 1, the openingis beveled inwardandappearsto havebeen madeby repetitive grooving with a sharp instrument Numerous scratchescan be seen on the outertable aroundthe marginsof the opening(Figure8). Cutmarksthatsuggestdefleshingarepresenton the squamousportionof the occipitalbone, on the rightparietalacrossthe temporalline on the maxilla and along the orbitalmarginof the left zygomatic.The preservedportionof the base of the skull shows no cut marksor fractures.The absence of damageto the lfaseof the skull is an importantdistinction from Nasca trophyheads from the south coast of Peru (see below), which invariablyshow damageto the base of the skullthatoccurreddursng removalof the braln(VeranoI9957 1997b). Cut marksare presenton the alveolarand nasal processesof the left maxillaandon the lateralaspect of the left zygomatic(Figure5). The mandiblehas four cut markson the posteriormarginof the left ascendingramusandnumeroussmallcutandscrape marksaroundthe mentalspinesanddigastricfossae on the posteriorsurfaceof the body. These marks appear to reflect intentional defleshing, and are importantin indicatingthat a fleshed head rather thana dry skull was selectedfor modification.Presumablythe vaultwas openedat this time as well to removethe brain. > & Interpretation Figure7a, b. Photograph(lower)and drawing(upper)of modifiedskullshad Skull 2. Cross-hatchedareas in the drawing indicate Priorto thisfinding,intentionally missingbones. notbeenreportediErom thenorthcoastof Peru.Exan- This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 66 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 10, No. 1, 1999] Figure8. Anteriormarginof vaultdefect,Skull2, showingscratches. ples of Mocheceramicjarsin theformof skullbowls areknown however(Figure9)*Thespecificfunction of thesejars is unknown,althoughthey areclearly vessels that cowldhold solids or liquids. Unfortunately the exarnpleswe have examinedin museum collectionsdo nothavegood archaeologicalcontext butpresumablythey were excavatedfromtombs. To make an actualskull hold liquid one would needto seal numerowsforaminaandfissuresorplace some formof bowl (wramic meAl orgourd)within the cranialcavity.No tracesof such a sealantor of bowls were foundin Skull 1 or 2, althoughit should be notedthatthe skullsarefragmentvyandverylittle of the cranialfossae are preserved.In addition preservationof organicremainsis generallypoor at Moche and gourds or organicsealants tnight not have preserved.Xurd platesand bowls are known to have been used extensively by the Mshe, but they are poorly representedin the archaeobgical record(Donnan1995: 143-146). The use of humanskulls as ceremonialdrinking vessels is not unknown in the Andes. One that belongedto the InkaAtahualpawas describedin a sixteenth-centuryaccount: "One of Atahualpa?s favouritepossessionswas the head of Atoc one of Huascs generals ..??Cristobalde Mena saw this '4headwithits skin,driedfleshandhair.Itsteethwere closed andheld a silverspout.On top of the heada golden bowl was attached.Atahualpaused to drink from it when he was remindedof the wars waged againsthim by his brother"(Hemming 1970:54). The Moche skulls may have serveda similarfunction althoughapparentlytheyweredefleshedrather than mummified. The fact that the two skulls belongedto youngadultmalesis significantas well? as a Moche sacrificialsite containingthe skeletal remainsof dozens of adolescentand young adult males was diseoveredin 1995in a courtyardbehind ffiePyramidof theMoon?approximately150m from ZUM 8 (Bvurget 1997a 1997b; Verano 1998b, This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions REPORTS Figure 9. Moche ceramic vessel in the form of a skull (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution,catalognumber148021.Height:15 cm; diameter of opening:9 cm). 1998c).Ceramicsassociatedwiththe sacrificialvictims and a radiocarbondate from a wooden post found in an associatedadobe platform(1470 + 80 B.P., Beta 96035; A.D. 425-690, 2 sigmas, calibrated)suggestthatthe modifiedskullsandthe sacrificialsite areroughlycontemporary. Decapitation and Modificationof HumanHeads Decapitation,usuallyat the handsof supernaturals, 67 is a relativelycommonthemein Mocheiconography (e.g., Donnan1978, figs. 106, 151, 152, 205; Moser 1974), and appearsto have deep rootsin the artistic traditionsof the northcoast of Peru(Cordy-Collins 1992, 1998).Moche artistsalso depicteddisembodied headsin scenesinvolvingthe sacrificeof prisoners (Figure10). Sometimesthe heads are shownas isolated elements, as in Figure 10, or placed atop poles (Benson 1972:Figure5-16). Some havea rope passedthroughthe mouth,apparentlyto allowthem to be carriedor tied to anotherobject(Figure11). Moche iconographysuggests thathumanheads were collected and manipulatedin various ways. Until recently,however,therewas no archaeological evidence to confirmthis. Recentdiscoveriesof decapitatedindividualsat the Pyramidof the Moon at Moche (Bourget1997a, 1997b) andat the Moche site of Dos Cabezasin the JequetepequeRivervalley (Cordy-Collins1998) providesome of the first osteological evidence of such behavior.The two skullsfromZUM 8 describedin thisreportaddnew informationon the postmortemfate of particular heads. Skulls 1 and 2 show differencesin preparation techniquethatmay be of significance.Forexample, Skull 2 does not have a mandible.Althoughit may have been presentat one time but lost priorto burial, the lack of drilledholes in the zygomaticarches indicatethatit wouldhavebeen attachedin a different mannerthanwas thecase in Skull 1. Skull2 also lacks a perforatedmastoidprocess.Althoughthese differencescouldreflectnothingmorethanindividual choices madeby the personpreparingthe skull, preparationdetailssuch as the presenceor absence - Figure10. Roll-outdrawingof a MocheIV vesselshowingthe arraignmentand sacrificeof prisoners.An isolatedhead, presumablyof a decapitatedvictim,can be seen in the lowerrightcorner(Vesselfromthe collectionsof theAmerican Museumof NaturalHLstory, NewYork;Drawingby DonnaMcClelland). This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions l 68 LATIN AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 10, No. 1,1999] Figure 12. Nasca trophy head. In this example the carrying cord is composed of hair cut from the victim's head (Courtesy of the Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Arqueologia, y Historia, Lima; catalog number AF: 7050). Figure 11. Moche depictions of heads with rope passed through the mouth: (a) from Donnan 197X:Figure 274; (b) detail of a spout and handle bottle in the collections of the Instituto Departmental de la Cultura, Trujillo (photograph courtesy of Christopher Donnan). of ear ornamentsmay have markedthe social rank of a victim or indicateddifferentuses for particular skulls.The postmortemloss of many teeth and the modificationandreinsertionof teethintoemptyalveoli does suggestthattherewas substantialuse of the skullspriorto theirburialin the niche. ComparativeData Although"trophyheads"arecommonin theiconography of many ancient Andean societies, actual examples of severed human heads and modified human skulls are relativelyrare (Verano1995). A notableexceptionaremummifiedheadsof theNasca culture of the south coast of Peru (Proulx 1971, 1989),of whichmorethan100 examplesareknown (Baraybar1987;Browneet al. 1993;Verano1995). Nascatrophyheadswerepreparedin a mannerquite distinctfrom thatof the skulls at Moche, involving removalof the brainthroughthe base of the skull and punchingout a small perforationin the frontal bone to attacha carryingcord (Baraybar1987;Verano 1995).Nascatrophyheadsweremummified,and well-preservedexamplesstill retainskin, hair,and carryingcords(Figure12).The orbitsandcheeksof many are stuffedwith cloth, apparentlyto give the heada lifelikeappearance.Nascaheadsdo not have anopeningatthetopof theskull,however;andcould not have served as drinklngvessels. They are thus quitedistinctin preparationandpresumedfunction fromthe modif1edskullsat Moche.Nevertheless,it is interestingto notesomesimilaritiesbetweenNasca trophyheadsandthe Moche skullsin theircuration andfinal deposition.Nasca trophyheads show evidence of having been carefullypreparedand preserved.The complex treatmentof the head, which includedremovalof the brain,muscles,andsoft tissue structuresat the base of the skull and the stuffing of cheeks and eye orbitsimpliesthatthey were preparedfor extendeduse and display.After some periodof use theseheadswerecarefullyburied.The mostfrequentlyobservedpatternis theburialof individualheadsorcachesof headsunderfloorsorwithin This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions REPORTS thefill of ceremonialarchitecture(NeiraandCoelho 1972; Proulx 1989).Althoughtwo caches of Nasca trophyheads have been found in cemeteries,only rarely do such heads occur as grave offerings in Nascatombs(Cannichael1988:482483). Themodified skullsfromMochearesimilarin showingcareful preparation as well as extendeduse as is indicated by missing andreplacedteeth.Moreover,they were recoverednot from a mortuarycontext but from a niche in an elite residential compound. It would appear that the Moche skulls, like Nasca trophy heads,werenotconsideredappropriate gravegoods, but were buriedas isolated offeringsfollowing an extendedperiodof use. Signiflcance of the Skulls from the Pyramids of Moche The two skulls describedin this reportare significantfor severalreasons.They arethe firstexamples of intentionallymodifiedskullsto be reportedfrom thenorthcoastof Peru,andthefirstosteologicalparallel forceramicskullvessels createdby Mocheartisans. The specific function of these vessels is unknown,as thereareno depictionsin Mocheartthat showthembeingheld or used.Presumablytheyhad some functionrelatedto the presentationand sacrifice of prisoners.Cut markson the skulls indicate clearlythatthey were preparedfrom fleshed heads andnotdryskulls.TheirdiscoveryatMoche,in close proximityto a sacrificialsite at the Pyramidof the Moon, and the fact thatboth skulls appearto be of youngadultmales,suggestthattheyweretakenfrom sacrificedcaptives.Moreresearchremainsto be done before the natureand context of human sacrifice amongtheMocheis fullyunderstood,butthesemodified skullscontributeto a growingbodyof evidence for sacrificialpracticespreviouslyknownonly from Moche iconography. Acknowledgments.The Proyecto Arqueologico Huaca de la Luna is grateful for financial support from the Union de Cervecerias PeruanasBackus y Johnston, the Municipalidad Provincial de Trujillo, Gobierno Regional de La Libertad, and the Universidad Nacional de Trujillo. Funding for Chapdelaine's research was provided by a three year grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Verano's research was made possible by a FulbrightLectureshipat the UniversidadNacional de Trujillo granted by the Council for the International Exchange of Scholars. Figure 1 is courtesy of Donald McClelland of the Fowler Museum of Cultural History; Figures 2 and 3 were drafted by Carlos Ayesta, and Figures S and 7 by Gustavo 69 Perez of the ProyectoArqueologico Huaca de la Luna;Figure 10 is courtesy of Donna McClelland. Finally, we are grateful for the suggestions and comments of four external reviewers. References Cited Alva, W., andC.B. Donnan 1993 RoyalTombsof Sipan.FowlerMuseumof CulturalHistory,Universityof California-LosAngeles. Baraybar,J. P. 1987 CabezastrofeoNasca:nuevasevidencias.GacetaArqueologicaAndina 15:6-10. Benson, E. P. 1972 TheMochica,a Cultureof Peru.Praeger,New York. Bourget,S. 1997a Las excavacionesen la Plaza3a. In Investigacionesen la Huaca de la Luna 1995, editedby S. Uceda, E. Mujica, and R. Morales,pp. 51-59. UniversidadNacional de Trujillo, Peru. 1997b La colere des ancetres:decouverted'un site sacrificiel a la Huacade la Luna,vallede Moche.InA I'ombredu Cerro Blanco, nouvelles de'couvertessur la cultureMoche, cote nord du Pe'rou,edited by C. Chapdelaine,pp. 83-99. Les cahiersd'anthropologieN° 1.Departementd'anthropologie, Universitede Montreal. Brewster-Wray, C. C. 1983 SpatialPatterningand the Functionof a HuariArchitecturalCompound.In Investigationsof the Andean Past, editedby D. Sandweiss,pp.122-135. LatinAmericanStudies Program,CornellUniversity,Ithaca. Browne,D. M., H. Silverman,andR. Garcia 1993 A Cacheof 48 NascaTrophyHeadsFromCerroCarapo, Peru.LatinAmericanAntiquity4: 27F294. Burger,R. L. 1984 ThePrehistoricOccupationof Chavinde Huantar,Peru. Universityof CaliforniaPress,Berkeley. Carmichael,P. H. 1988 Nasca MortuaryCustoms:Death and AncientSociety on the South Coast of Peru. Ph.D. dissertation,University of Calgary.UniversityMicrofilms,Ann Arbor. Chapdelaine,C. (editor) 1997 A l'ombredu CerroBlanco, nouvellesde'couvertessur la cultureMoche, cote nord du Pe'rou.Les cahiers d'anthropologieN° 1. Departementd'anthropologie,Universite de Montreal,Quebec. Cordy-Collins,A. 1992 Archaism or Tradition?The Decapitation Theme in CupisniqueandMocheIconography.LatinAmericanAntiquity3:206-220. 1998 Off with TheirHeads:Decapitationin Cupisniqueand EarlyMoche. In RitualSacrificeinAncientPeru:New Discoveries and Interpretations,edited by E. Benson and A. Cook. Manuscripton file, Departmentof Anthropology, CatholicUniversityof America,Washington,D.C. Donnan,C. B. 1973 MocheOccupationof theSantaValley,Peru.University of CaliforniaPublicationsin Anthropology8. Universityof CaliforniaPress,Berkeley. 1978 MocheArt of Peru:Pre-ColumbianSymbolicCommunication. Museum of CulturalHistory,Universityof California,Los Angeles. 1995 Moche FuneraryPractice. In Tombsfor the Living: AndeanMortuaryPractices, edited by T. D. Dillehay, pp. 111-160. DumbartonOaks,Washington,D.C. Donnan,C. B., andL. J. Castillo 1994 Excavacionesde tumbasde sacerdotisasMoche en San Jose de Moro, Jequetepeque.In Moche,propuestasy per- This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 70 LATINAMERICANANTIQUITY [Vol. 10, No. 1,1999] spectivas, Actas del Primer Coloquio sobre la Cultura Uceda, S., and R. Morales(editors) Moche,editedby S. UcedaandE. Mujica,pp.415424. Uni1993 Informesegundatemporada,1992, Proyectode InvesversidadNacionalde Trujillo,Peru. tigacion y ConservacionHuaca de la Luna. Universidad Hemming,J. Nacionalde Trujillo,Trujillo,Peru. 1970 TheConqzcest of the Incas. HarcourtBraceJovanovich, 1994 Informeterceratemporada,1993, Proyectode InvestiNew York. gacion y Conservacion Huaca de la Luna. Universidad Kroeber,A. L. Nacionalde Trujillo,Trujillo,Peru. 1925 The Uhle PotteryCollectionsFromMoche. University 1996 Informete'cnico,1995, ProyectoArqueologico Huacade of CaliforniaPublications in AmericanArchaeologyand la Luna.UniversidadNacionalde Trujillo,Trujillo,Peru. Ethnology21(5):191-234. Uceda, S., E. Mujica,and R. Morales(editors) LarcoHoyle, R. 1997 Investigacionesen la Huaca de la Luna 1995. Univer1938 Los mochicas.Tomo1. CasaEditoraLa Cronicay VarsidadNacionalde Trujillo,Peru. iedadesS.A., Lima. Uhle, M. 1939 Los mochicas.Tomo2. CasaEditoraLa Cronicay Var1915 Las ruinasde Moche. Boletin de la Sociedad GeograiedadesS.A., Lima. fica de Lima30(3):57-71. Lastres,J. B., andF. Cabieses Verano,J. W. 1960 La trepanaciondel craneo en el antiguoPeru.Univer1995 WhereDo They Rest?The Treatmentof HumanOffersidadNacionalMayorde San Marcos,Lima. ings andTrophiesin AncientPeru.In Tombsfor the Living: Lisowski,F. P. AndeanMortuaryPractices, edited by T. D. Dillehay,pp. 1967 PrehistoricandEarlyHistoricTrepanation.In Diseases 189-227. DumbartonOaks,Washington,D.C. in Antiquity,editedby D. R. BrothwellandA.T. Sandison, 1997a Physical Characteristicsand Skeletal Biology of the pp. 651-672. CharlesC. Thomas,Springfield,Illinois. MochePopulationatPacatnamu.In ThePacatnamuPapers, McEwan,G. Volume2: TheMoche Occupation,editedby C. B. Donnan 1987 TheMiddleHorizonin the Valleyof Cuzeo,Peru: The andG. A. Cock, pp.189-214. Museumof CulturalHistory, Impact of the WariOccupationof Pikillacta in the Lucre Universityof California,Los Angeles. Basin. BAR InternationalSeries 372. BritishArchaeologi1997b Advances in the Paleopathology of Andean South cal Reports,Oxford. America.Journalof WorldPrehistory11: 237-268. McKern,T. W. 1998a La trepanacioncomo tratamientoterapeuticoparafrac1970 Estimationof SkeletalAge: FromPubertyto About 30 turas craneales en el antiguo Peru. In Estudios de Yearsof Age. In PersonalIdentificationin Mass Disasters, antropologia biologica (VIII Coloquio Internacional de editedby T. D. Stewart,pp. 41-56. SmithsonianInstitution AntropologfaFisica "Juan Comas," 1995).: Institutode Press,Washington,D.C. Investigaciones Antropologicas de UNAM, Instituto Moser,C. L. Nacionalde Antropologiae Historia,andAsociacionMex1974 Ritual Decapitation in Moche Art. Archaeology icanade AntropologiaBiologica, Mexico (in press). 27(1):3s37. 1998b Sacrificioshumanos,desmembramientosy modificaNeira,M., andV. P. Coelho ciones culturalesen restos osteologicos: evidenciasde las 1972 Enterramientos de Cabezasde la CulturaNasca.Revista temporadasde investigacion 1995-96 en la Huaca de la do MuseuPaulista,N.s. 20: 109-142. Luna.InInvestigacionesen la Huacade la Luna1996,edited Proulx,D. A. by S. Uceda and E. Mujica.UniversidadNacional de Tru1971 HeadhuntinginAncientPeru.Archaeology24(1):16-21. jillo, Peru,pp. 159-171. 1989 Nasca TrophyHeads:Victimsof Warfareor RitualSac1998c The PhysicalEvidenceof HumanSacrificein Ancient rifice?.In Culturesin Conflict:CurrentArchaeological PerPeru.In RitualSacrificein AncientPeru:New Discoveries spectives, edited by D. C. Tkaczukand B. C. Vivian, pp. andInterpretations, editedby E. BensonandA. Cook. Man73-85. Universityof CalgaryArchaeologicalAssociation, uscripton file, Departmentof Anthropology,CatholicUniCalgary. versityof America,Washington,D.C. Shimada,I. 1994 PampaGrandeand theMochica Culture.Universityof ReceivedApril2, 1998; acceptedMay 26, 1998; revisedJuly23, TexasPress,Austin. 1998. This content downloaded from 129.252.86.83 on Wed, 12 Mar 2014 18:12:23 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions