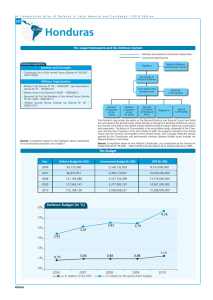

Number 0.- December 2012.- English

Anuncio