Summarization of specialized discourse

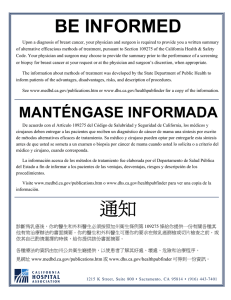

Anuncio