A Tale of Two Cities - Cambridge University Press

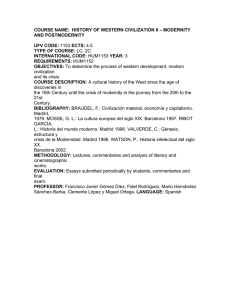

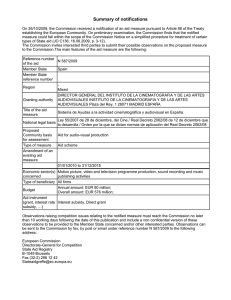

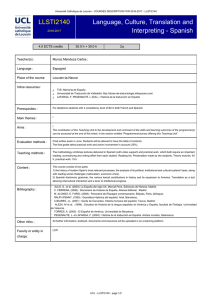

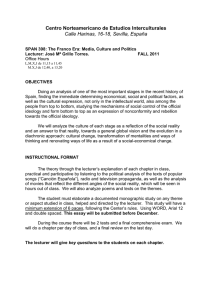

Anuncio