PENSAMIENTO PROPIO 41

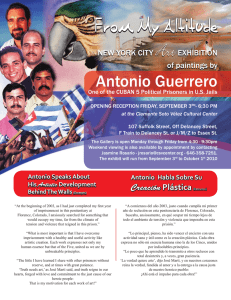

Anuncio