03-120 (Anatomía de la vaina)

Anuncio

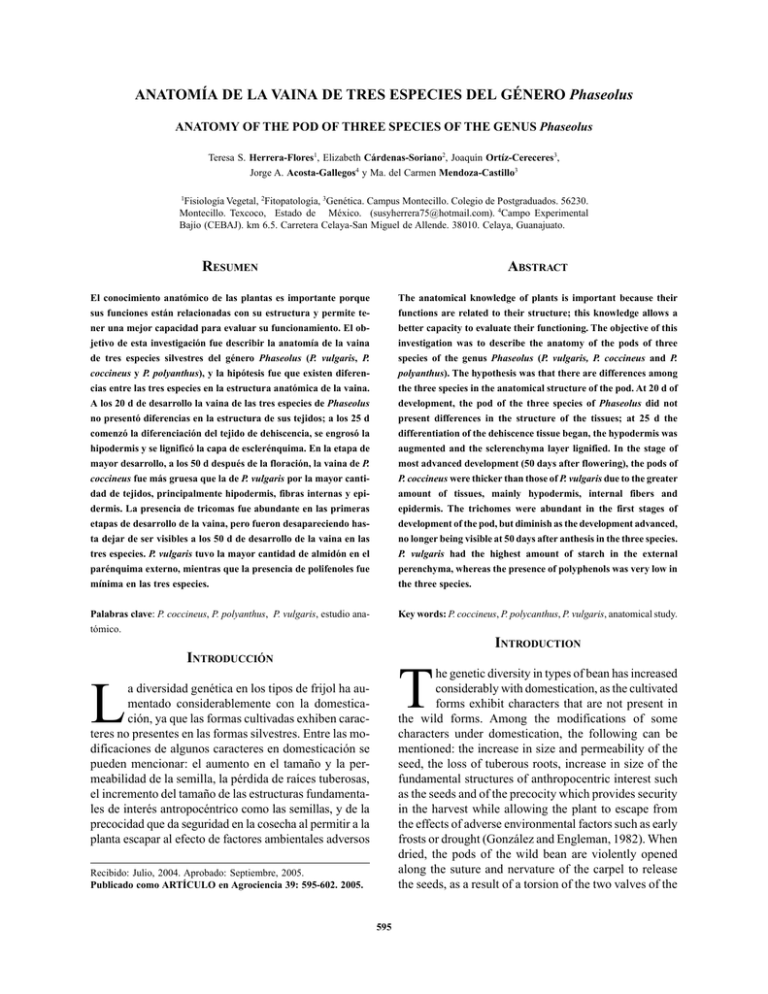

ANATOMÍA DE LA VAINA DE TRES ESPECIES DEL GÉNERO Phaseolus ANATOMY OF THE POD OF THREE SPECIES OF THE GENUS Phaseolus Teresa S. Herrera-Flores1, Elizabeth Cárdenas-Soriano2, Joaquín Ortíz-Cereceres3, Jorge A. Acosta-Gallegos4 y Ma. del Carmen Mendoza-Castillo3 1 Fisiología Vegetal, 2Fitopatología, 3Genética. Campus Montecillo. Colegio de Postgraduados. 56230. Montecillo. Texcoco, Estado de México. ([email protected]). 4Campo Experimental Bajío (CEBAJ). km 6.5. Carretera Celaya-San Miguel de Allende. 38010. Celaya, Guanajuato. RESUMEN ABSTRACT El conocimiento anatómico de las plantas es importante porque sus funciones están relacionadas con su estructura y permite tener una mejor capacidad para evaluar su funcionamiento. El objetivo de esta investigación fue describir la anatomía de la vaina de tres especies silvestres del género Phaseolus (P. vulgaris, P. coccineus y P. polyanthus), y la hipótesis fue que existen diferencias entre las tres especies en la estructura anatómica de la vaina. A los 20 d de desarrollo la vaina de las tres especies de Phaseolus no presentó diferencias en la estructura de sus tejidos; a los 25 d comenzó la diferenciación del tejido de dehiscencia, se engrosó la hipodermis y se lignificó la capa de esclerénquima. En la etapa de mayor desarrollo, a los 50 d después de la floración, la vaina de P. coccineus fue más gruesa que la de P. vulgaris por la mayor cantidad de tejidos, principalmente hipodermis, fibras internas y epidermis. La presencia de tricomas fue abundante en las primeras etapas de desarrollo de la vaina, pero fueron desapareciendo hasta dejar de ser visibles a los 50 d de desarrollo de la vaina en las tres especies. P. vulgaris tuvo la mayor cantidad de almidón en el parénquima externo, mientras que la presencia de polifenoles fue mínima en las tres especies. The anatomical knowledge of plants is important because their functions are related to their structure; this knowledge allows a better capacity to evaluate their functioning. The objective of this investigation was to describe the anatomy of the pods of three species of the genus Phaseolus (P. vulgaris, P. coccineus and P. polyanthus). The hypothesis was that there are differences among the three species in the anatomical structure of the pod. At 20 d of development, the pod of the three species of Phaseolus did not present differences in the structure of the tissues; at 25 d the differentiation of the dehiscence tissue began, the hypodermis was augmented and the sclerenchyma layer lignified. In the stage of most advanced development (50 days after flowering), the pods of P. coccineus were thicker than those of P. vulgaris due to the greater amount of tissues, mainly hypodermis, internal fibers and epidermis. The trichomes were abundant in the first stages of development of the pod, but diminish as the development advanced, no longer being visible at 50 days after anthesis in the three species. P. vulgaris had the highest amount of starch in the external perenchyma, whereas the presence of polyphenols was very low in the three species. Palabras clave: P. coccineus, P. polyanthus, P. vulgaris, estudio anatómico. Key words: P. coccineus, P. polycanthus, P. vulgaris, anatomical study. INTRODUCTION INTRODUCCIÓN T he genetic diversity in types of bean has increased considerably with domestication, as the cultivated forms exhibit characters that are not present in the wild forms. Among the modifications of some characters under domestication, the following can be mentioned: the increase in size and permeability of the seed, the loss of tuberous roots, increase in size of the fundamental structures of anthropocentric interest such as the seeds and of the precocity which provides security in the harvest while allowing the plant to escape from the effects of adverse environmental factors such as early frosts or drought (González and Engleman, 1982). When dried, the pods of the wild bean are violently opened along the suture and nervature of the carpel to release the seeds, as a result of a torsion of the two valves of the L a diversidad genética en los tipos de frijol ha aumentado considerablemente con la domesticación, ya que las formas cultivadas exhiben caracteres no presentes en las formas silvestres. Entre las modificaciones de algunos caracteres en domesticación se pueden mencionar: el aumento en el tamaño y la permeabilidad de la semilla, la pérdida de raíces tuberosas, el incremento del tamaño de las estructuras fundamentales de interés antropocéntrico como las semillas, y de la precocidad que da seguridad en la cosecha al permitir a la planta escapar al efecto de factores ambientales adversos Recibido: Julio, 2004. Aprobado: Septiembre, 2005. Publicado como ARTÍCULO en Agrociencia 39: 595-602. 2005. 595 AGROCIENCIA, NOVIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE 2005 como las heladas tempranas o la sequía (González y Engleman, 1982). Las vainas del frijol silvestre al secar se abren violentamente a lo largo de la sutura y nervadura del carpelo para liberar las semillas, como resultado de una torsión de las dos valvas del fruto en sentidos opuestos, ocasionada por la contracción de las células esclerenquimatosas de las paredes del fruto (Esau, 1982). En contraste, en las formas domesticadas se ha ido perdiendo esta facultad y los frutos (vainas) generalmente permanecen cerrados o se abren ligeramente. Anatomía de la vaina de frijol Los primeros trabajos reportados en la literatura sobre la anatomía y la dehiscencia de la vaina dentro del género Phaseolus, se refieren únicamente a la especie P. vulgaris (frijol común). Revé y Brown (1968) describieron la vaina en botón floral, flor abierta y vainas desarrolladas. En el botón floral la pared de la vaina está formada de tejido parenquimatoso limitado por una epidermis externa y una interna, dentro de las cuales hay una capa de células denominadas hipodermis externa e interna. Cuando la flor se abre, la hipodermis y la epidermis internas originan al parénquima interno que rodea a la cavidad del fruto y la capa interna de fibras esclereidas. Después de la floración, las fibras esclereidas de la capa interna engruesan sus paredes. A lo largo de la sutura y nervadura dorsales existen haces vasculares rodeados de fascículos de esclereidas. Delgado (1992)5 observó, en la variedad Black Valentine, ocho a nueve estratos de células, en Black Wax siete a ocho estratos en el tejido externo y cinco a seis en el interno. Smartt (1942) señaló que en los frijoles cultivados hay una tendencia a reducir la dehiscencia, lo cual no implica cambios anatómicos notables en relación con los tipos silvestres; además, en domesticación, el contenido de fibras se ha reducido más en P. vulgaris que en P. coccineus. La cantidad de fibras es un carácter gobernado genéticamente, pero es influenciado por factores ambientales como la humedad atmosférica y la temperatura (Revé y Brown, 1968). En P. coccineus (Tacahuáquetl semidomesticado), P. coccineus silvestre y P. coccineus subespecie polyanthus, ayocote y acalete domesticados, el desarrollo ontogénico de la vaina de tacahuáquetl ayocote y acalete domesticado es semejante, aunque en el primero el engrosamiento de las paredes de esclerénquima interno y longitudinal es más precoz. (González y Engleman, 1982). P. coccineus subespecie polyanthus (acalete) tiene una red adicional de haces de floema y ausencia de células con taninos en la pared lateral del floema. El espesor de la pared de las esclereidas de la capa interna de fruit in opposite directions, caused by the contraction of the sclerenchyma cells of the walls of the fruit (Esau, 1982). In contrast, in the domesticated forms, this faculty has been disappearing and the fruits (pods) generally remain closed or slightly open. Anatomy of the bean pod The first studies reported in the literature on the anatomy and the dehiscence of the pod within the genus Phaseolus, refer only to the species P. vulgaris (common bean). Revé and Brown (1968) described the pod in floral bud, open flower and developed pods. In the floral bud, the wall of the pod is formed of perenchymatose tissue limited by an external and an internal epidermis, within which there is a layer of cells called external and internal hypodermis. When the flower opens, the internal hypodermis and epidermis give way to the internal perenchyma that surrounds the fruit cavity and the internal layer of sclereid fibers. After flowering, the sclereid fibers of the internal layer thicken the walls. Along the dorsal suture and nervature, there are vascular fascicles surrounded by sclereid fascicles. Delgado (1992)5 observed in the Black Valentine variety eight to nine layers of cells, in Black Wax seven to eight layers in the external tissue and five to six in the internal tissue. Smartt (1942) pointed out that in cultivated beans, there is tendency to reduce dehiscence, which does not imply noticeable anatomical changes with respect to the wild types; furthermore, under domestication, the fiber content has been reduced more in P. vulgaris than in P. coccineus. The fiber content is a genetically governed character, but it is influenced by environmental factors such as atmospheric humidity and temperature (Revé and Brown, 1968). In P. coccineus (semi-domesticated Tacahuáquetl), wild P. coccineus and P. coccineus subspecies polyanthus, domesticated ayocote and acalete, the onthogenic development of the pod of tacahuáquetl ayocote and domesticated acalete is similar, although in the former, the thickening of the walls of the internal and longitudinal sclerenchyma is more precocious (González and Engleman, 1982). P. coccineus subspecies polyanthus (acalete) has an additional network of fascicles of phloem and an absence of cells with tannins in the lateral wall of the phloem. The thickness of the wall of the sclereids of the internal layer of sclerenchyma, along with the diameter of these cells, is greater in the dehiscente than in the indehiscent genotypes. The number of rows of internal sclereids is greater in the wild bean than in the semi-domesticated and domesticated types. The principal 5 Delgado, A. A. 1992. Metabolitos formados por la fijación de 14CO2 en la cavidad de la vaina de Phaseolus vulgaris L. Tesis de Maestría en Ciencias. Colegio de Postgraduados. Montecillo, Estado de México. 138 p. 596 VOLUMEN 39, NÚMERO 6 ANATOMÍA DE LA VAINA DE TRES ESPECIES DEL GÉNERO Phaseolus esclerénquima, así como el diámetro de estas células, es mayor en los genotipos dehiscentes que en los indehiscentes. El número de hileras de esclereidas internas es mayor en el frijol silvestre que en los tipos semidomesticados y domesticados. El presente trabajo tuvo como objetivo principal describir la anatomía de la vaina de P. vulgaris (frijol común), P. coccineus (ayocote) y P. polyanthus (gordo) en cinco estadios de desarrollo. MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS Semillas de P. vulgaris (frijol común), P. coccineus (ayocote) y P. polyanthus (gordo) (Cuadro 1), se sembraron en invernadero el 22 de marzo de 2002 y se trasplantaron el l9 de abril del mismo año, en el Campo Experimental del Colegio de Postgraduados en Montecillo, México situado a 19° 29’ N y 98° 51’ O, a una altura de 2240 m. El clima es C(wo)(w) big (sistema de Koëpen modificado por García, 1981). El hábito de crecimiento de las tres especies silvestres es trepador Tipo IV, se caracteriza porque a partir de la primera hoja trifoliolada el tallo desarrolla una mayor capacidad de torsión que se manifiesta en su capacidad para trepar, tiene ramas muy poco desarrolladas debido a la alta dominancia apical, el tallo principal puede tener 20 a 30 nudos y alcanzar más de 2 m de altura con un soporte adecuado. En la planta se presentan simultáneamente las etapas de floración, formación, llenado y maduración de vainas y también se presenta el crecimiento vegetativo (CIAT, 1984). De cada genotipo de Phaseolus se tomaron tres vainas a los 10, 20, 25, 35 y 50 d después de la floración para realizar el estudio anatómico; a los 50 d después de la floración se recolectaron 10 vainas, y se midió la longitud y anchura, y se calculó la correlación entre estas dos variables (SAS, 1999). También se midió el grosor en micrómetros de los tejidos y cutícula de la vaina de las tres especies silvestres. Estudio anatómico Para el estudio anatómico de las vainas se tomaron fracciones de 0.5 cm en los dos extremos, que se fijaron en Craf III solución A (ácido crómico 60 mL, ácido acético 40 mL, aforada a 1 L con agua destilada), Solución B (formaldehído 228 mL y agua destilada 772 mL). El material fijado se lavó y deshidrató en una serie gradual de alcohol etílico y se infiltró en paraplast (SIGMA Chemical Co. USA) en un procesador automático de tejidos (Sakura Fingtechnical, Tissue-Tek II. Mod. 4640B. Co., LTD. Tokio, Japón). Se hicieron moldes de papel y las fracciones de tejido se colocaron individualmente en cada molde con parafina, orientándose para un corte transversal. Los bloques objective of the present study was to describe the anatomy of the pod of P. vulgaris (common bean), P. coccineus (ayocote) and P. polyanthus (fat) in five stages of development. MATERIALS AND METHODS Seeds of P. vulgaris (common bean), P. coccineus (ayocote) and P. polyanthus (fat) (Table 1), were sown in a greenhouse on March 22 of 2002 and transplanted on April 19 of the same year, in the Experimental Field of the Colegio de Postgraduados in Montecillo, México, located at 19° 29’ N and 98° 51°’ W, at an altitude of 2240 m. The climate is C(wo)(w) big (system of Koëpen, modified by García, 1981). The growth habit of the three species is Type IV climbing; it is characterized because starting from the first trifoliate leaf, the stem develops a greater torsion capacity which is manifested in its climbing capacity, it has branches that are only slightly developed due to the high apical dominance, the main stem may have 20 to 30 nodes and reach a height of over 2 m with adequate support. The plant simultaneously presents the stages of flowering, formation, fill and maturation of pods and also presents vegetative growth (CIAT, 1984). From each genotype of Phaseolus, three pods were taken at 10, 20, 25, 35 and 50 d after flowering to carry out the anatomical study; at 50 d after flowering 10 pods were collected, the length and width were measured, and the correlation between these two variables were measured (SAS, 1999). The thickness was also measured in micrometers of the tissues and cuticle of the pod of the three wild species. Anatomical study For the anatomical study of the pods, fractions of 0.5 cm were taken from the two extremes, and fixed in Craf III solution A (60 mL chromic acid, 40 mL acetic acid, gauged to 1 L with distilled water), Solution B (228 mL formaldehyde and 772 mL distilled water). The fixed material was washed and dehydrated in a gradual series of ethylic alcohol and was infiltrated in paraplast (SIGMA Chemical Co. USA) in an automatic tissue processer (Sakura Fingtechnical, Tissue-Tek II. Mod. 4640B. Co., LTD. Tokio, Japan). Paper molds were made and the tissue fractions were individually placed into each mold with paraffin, oriented for a transversal cut. The paraffin blocks were left to solidify at room temperature and then mounted on wooden supports. The material included in paraplast was cut with a rotary microtome (Spencer, American Optical Company Mod. 820). From each sample, 10 cuttings were obtained with a thickness of 8 µm, which were placed in a flotation bath (water and gelatin) at ±70 °C; the cuttings were Cuadro 1. Especies de Phaseolus utilizadas en el experimento. Montecillo, México. 2002. Table 1. Species of Phaseolus utilized in the experiment. Montecillo, México. 2002. Especie P. polyanthus P. coccineus P. vulgaris Nombre común Gordo Ayocote Garbancillo Zarco Origen Sierra Norte de Puebla, Puebla Amecameca Estado de México Arandas, Jalisco Hábito de crecimiento Categoría Color de semilla Tipo IV Tipo IV Tipo IV Criollo Criollo Criollo Crema Morado Crema HERRERA-FLORES et al. 597 AGROCIENCIA, NOVIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE 2005 de parafina se dejaron solidificar a temperatura ambiente y se montaron en soportes de madera. El material incluido en paraplast se cortó con un micrótomo rotatorio (Spencer, American Optical Company Mod. 820). De cada muestra se obtuvieron 10 cortes de 8 µm de grosor, los cuales se colocaron en baño de flotación (agua y grenetina) a ±70 °C; los cortes se extendieron y adhirieron a los portaobjetos. Los cortes se desparafinaron, hidrataron en una serie gradual de alcohol etílico y se tiñeron con los colorantes safranina-verde rápido (Curtis, 1986; Sass, 1958). La observación de las preparaciones histológicas y el registro fotográfico se hizo con un fotomicroscopio Ultraphot II Carl Zeiss. Los reactivos usados para determinar la presencia de polifenoles y granos de almidón en las vainas de 50 d de desarrollo fueron permanganato de potasio (KMNO4) y lugol (KI+I). En las tres últimas etapas de desarrollo de la vaina se hicieron reaccionar cortes longitudinales con fluoroglucina + ácido clorhídrico, para determinar el estado de desarrollo de las fibras y su lignificación. Para identificar y medir el grosor de la cutícula los cortes se tiñeron con Sudán IV (Curtis, 1986). Además se midió la epidermis externa, hipodermis y grosor de la capa de esclerénquima con un portaobjetos graduado y con los datos obtenidos se realizó una prueba de Tukey de comparación de medias (SAS, 1999) para identificar diferencias estadísticas entre los tejidos de cada especie. RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN Se encontró una correlación significativa entre la longitud y anchura de diez vainas de las tres especies durante el desarrollo de la vaina (Cuadro 2); es decir, al aumentar la longitud se incrementó el ancho de la vaina debido al desarrollo de la semilla. P. coccineus tuvo el valor de correlación más alto, P. polyanthus el más bajo, y P. vulgaris un valor intermedio. Díaz (1990) mencionó que la vaina del frijol tiene un crecimiento acelerado en los primeros 12 d después de la antesis (floración) y 6 d después la semilla empieza a desarrollarse continuando su crecimiento aun cuando la vaina haya alcanzado su máxima longitud. En los primeros 20 d de desarrollo de la vaina de las tres especies de Phaseolus no se presentaron diferencias en la estructura de los tejidos (Cuadro 3). Se observó una capa de epidermis externa, y una capa de hipodermis con células Cuadro 2. Coeficientes de correlación entre la longitud y anchura de las vainas de las tres especies de Phaseolus. Montecillo, México. 2002. Table 2. Coefficients of correlation between the length and width of the pods of the three species of Phaseolus. Montecillo, México. 2002. Genotipo Valor de correlación P. coccineus P. vulgaris P. polyanthus † Significativo, p≤0.05. 598 VOLUMEN 39, NÚMERO 6 0.95† 0.90† 0.70† extended and adhered to microscope slides. The cuttings were deparaffinized, hydrated in a gradual series of ethylic alcohol and stained with the safranin-rapid green colorants (Curtis, 1986; Sass, 1958). The observation of the histological preparations and the photographic register was made with an Ultraphot II photomicroscope (Carl Zeiss). The reactives used to determine the presence of polyphenols and starch grains in the pods at 50 d of development were potassium permanganate (KMNO4) and lugol (KI+I). In the three final stages of development of the pod, longitudinal cuts were made to react with fluoroglucine + hydrochloric acid, to determine the development stage of the fibers and their lignification. To identify and measure the thickness of the cuticle, the cuts were stained with Sudán IV (Curtis, 1986). In addition, measurement was taken of the external epidermis, hypodermis and thickness of the sclerenchyma with a graduated slide, and with the data obtained a Tukey means comparison test (SAS, 1999) was carried out to identify statistical differences among the tissues of each species. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION A significant correlation was found between the length and width of three pods of the three species during pod development (Table 2); that is, as the length increased, the width of the pod increased due to the development of the seed. P. coccineus had the highest correlation value, P. polyanthus the lowest, and P, vulgaris had an intermediate value. Díaz (1990) mentioned that the bean pod has an accelerated growth in the first 12 d after anthesis (flowering) and 6 d after the seed begins to develop, continuing to grow even when the pod has reached its maximum length. In the first 20 of development of the pod of the three species of Phaseolus, no differences were found in the structure of any of the tissues (Table 3). A layer of external epidermis was observed, along with a Cuadro 3. Tejidos y sustancias ergásticas en vainas de tres especies de Phaseolus a los 10 y 20 d de desarrollo. Montecillo, México. 2002. Table 3. Tissues and ergastic substances in pods of three species of Phaseolus at 10 and 20 days of development. Montecillo, México. 2002. Tejido Epidermis Hipodermis PE HV Tricomas PI Polifenoles Almidón P. coccineus P. vulgaris P. polyanthus Uniestratificada S S AV AG Si En la epidermis En el P E Uniestratificada S S AV AG Si En la epidermis En el P E Uniestratificada S S AV AG Si En la epidermis En el P E P E = parénquima externo; P I = parénquima interno; H V = haces vasculares; A G = alargados y glandurales; AV = alrededor de la vaina; S = si. ANATOMÍA DE LA VAINA DE TRES ESPECIES DEL GÉNERO Phaseolus pequeñas en el estado de desarrollo estudiado. Enseguida se encontró una capa interna de esclerénquima y, por último, varias hileras de parénquima interno; a lo largo de la nervadura dorsal y de la sutura del fruto se observaron varios haces vasculares rodeados de escleréquima (Figura 1). Estos resultados coinciden con los de González y Engleman (1982) en vainas de P. coccineus, excepto que estos autores encontraron una capa extra de floema cercana a la capa de escleréquima. En los tres últimos muestreos (25, 35 y 50 d después de la floración) de la vaina de las tres especies de Phaseolus, se observaron cambios anatómicos: a los 25 d se inició la diferenciación del tejido de dehiscencia, localizado en la sutura ventral de la vaina (Figuras 2a y 2b) y las fibras comenzaron a presentar una coloración roja en los extremos de las células (Figura 3); a los 50 d se observó claramente toda la pared celular roja, indicando una completa lignificación de las células y ya no se observaron los tricomas. Conforme las vainas se desarrollaron a partir de 25 d, las células de la hipodermis fueron más grandes, alargadas y con paredes gruesas, dando lugar a las fibras externas; luego se observaron varias capas de parénquima externo limitado por haces vasculares con pocos cloroplastos. Las mediciones de la epidermis externa, hipodermis y esclerénquima (Cuadro 4), indican que la epidermis e hipodermis en P. coccineus fueron más gruesas, no así la capa de esclerénquimas; P. vulgaris presentó tejidos más delgados, quedando como intermedio P. polyanthus. También se observó que la cutícula fue más gruesa en P. coccineus que en las otras dos especies (Figura 4). layer of hypodermis with small cells in the development stage under study. Then an internal layer of sclerenchyma was found, and finally, various layers of internal parenchyma; along the dorsal nervature and the suture of the fruit, various vascular fascicles were observed surrounded by sclerenchyma (Figure 1). These results coincide with those of González and Engleman (1982) in pods of P. coccineus, except that these authors found an extra layer of floem near the layer of sclerenchyma. In the last three samplings (25, 35 and 50 d after flowering) of the pod of the three species of Phaseolus, anatomical changes were observed: at 25 d the differentiation began of the dehiscence tissue, located in the ventral suture of the pod (Figures 2a and 2b), and the fibers began to present a red coloration at the ends of the A pe e td B et ▼ ▼ h td pe hv pi e Figura 1. Fotomicrografía de la vaina de Phaseolus vulgaris a los 25 d de desarrollo. Corte transversal. Epidermis con tricomas (et); hipodermis (h); parénquima externo (pe); parénquima interno (pi); haces vasculares (hv); esclerénquima (e). (10X). Figure 1. Photomicrography of the pod of Phaseolus vulgaris at 25 d of development. Transversal cut. Epidermis with trichomes (et); hypodermis (h); external parenchyma (pe); internal parenchyma (pi); vascular fascicles (hv); sclerenchyma (e). (10X). Figura 2. A) Fotomicrogafía de la vaina de P. vulgaris a los 35 d de desarrollo. Corte transversal. Tejido de dehiscencia (td); parénquima externo (pe); y esclerénquima (e). (40X). B) Fotomicrogafía de la vaina de P. vulgaris a los 35 d de desarrollo. Corte longitudinal. Tejido de dehiscencia (td). (40x). Figure 2. A) Photomicrography of the pod of P. vulgaris at 35 d o development. Transversal cut. Dehiscence tissue (td); external parenchyma (pe); and sclerenchyma (e). (40X). B) Photomicrography of the pod of P. vulgaris at 35 d of development. Longitudinal cut. Dehiscence tissue (td). (40x). HERRERA-FLORES et al. 599 AGROCIENCIA, NOVIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE 2005 c pe e fe e Figura 3. Fotomicrogafía de la vaina de P. vulgaris a los 35 d de desarrollo. Corte longitudinal. Capas de esclerénquima (e); paréquima externo (pe). (40x). Figure 3. Photomicrography of the pod of P. vulgaris at 35 d of development. Longitudinal cut. Layers of sclerenchyma (e); external parenchyma (pe). (40x). µm X 10000) de tejidos y cutíCuadro 4. Grosor en micrómetros (µ cula de la vaina de tres especies de Phaseolus. Montecillo, México. 2002. µm X 10000) of tissues and Table 4. Thickness in micrometers (µ cuticle of the pod of three species of Phaseolus. Montecillo, México. 2002. Tejido P. vulgaris Fibras internas Esclerénquima Epidermis Fibras externas (hipodermis) Cutícula 0.92 a 0.54 b 0.73 b 1.9 b 0.29 b P. polyanthus 0.85 a 0.81 a 0.64 b 4.8 a 0.26 b VOLUMEN 39, NÚMERO 6 p P. coccineus 3.42 0.64 1.13 2.13 0.95 b b a b a El tejido de dehiscencia no se cuantificó. Solamente se observó en campo que las especies P. polyanthus y P. vulgaris presentaron mayor cantidad de vainas dehiscentes en relación con P. coccineus cuando la humedad relativa era 25%. En la epidermis de las tres especies de Phaseolus hubo presencia de polifenoles (35 d de desarrollo de la vaina) al igual que en algunas células del parénquima externo, que rodeaba a la capa de esclerénquima, pero en menor cantidad (Figura 4). En P. vulgaris y P. polyanthus el espacio que ocupaban los polifenoles en las células era pequeño, mientras que en P. coccineus el espacio ocupado fue mayor, aunque la presencia de estos compuestos fue mínima en las tres especies (Figura 5). En todas las células del parénquima en vainas de 50 d de desarrollo de P. vulgaris y P. polyanthus se observaron granos de almidón (Figura 6), pero en P. polyanthus éste se concentró en mayor proporción en las células más cercanas a la capa de esclerénquima, y en P. coccineus el almidón se encontró sólo en las células de parénquima 600 Figura 4. Fotomicrogafía de la vaina de P. vulgaris a los 50 d de desarrollo. Corte transversal. Cutícula (c); epidermis (e); fibras externas (fe). (40x). Figure 4. Photomicrography of the pod of P. vulgaris at 50 d of development. Transversal cut. Cuticle (c); epidermis (e); external fibers (fe). (40x). a Figura 5. Fotomicrogafía de la vaina de P. coccineus a los 50 d de desarrollo. Corte transversal. Polifenoles presentes en la epidermis (p) y granos de almidón (a) de P. vulgaris. (10X). Figure 5. Photomicrography of the pod of P. coccineus at 50 d of development. Transversal cut. Polyphenols present in the epidermis (p) and starch grains (a) of P. vulgaris. (10X). cells (Figure 3); at 50 d it was clearly observed that the entire cell wall was red, indicating a complete lignification of the cells, and the trichomes were no longer observed. As the cells developed after 25 d, the cells of the hypodermis were larger, elongated and with thickened walls, giving way to external fibers; then various layers of external parenchyma were observed, bordered by vascular fascicles with few chloroplasts. The measurements of the external epidermis, hypodermis and sclerenchyma (Table 4) indicate that the epidermis and hypodermis in P. coccineus were thicker, but not the parenchyma layer; P. vulgaris presented thinner tissues, and P. polyanthus was intermediate. It was also observed ANATOMÍA DE LA VAINA DE TRES ESPECIES DEL GÉNERO Phaseolus a es Figura 6. Fotomicrogafía de la vaina de P. polyanthus a los 50 d de desarrollo. Corte transversal. Cantidad de gránulos de almidón (a); capa de esclerénquima (es). (40x). Figure 6. Photomicrography of the pod of P. polyanthus at 50 d of development. Transversal cut. Quantity of starch grains (a); layer of sclerenchyma (es). (40x). e pe a that the cuticle was thicker in P. coccineus than in the other two species (Figure 4). The dehiscence tissue was not quantified. It was only observed in the field that the species P. polyanthus and P. vulgaris presented a greater quantity of dehiscent pods with respect to P. coccineus when the relative humidity was 25%. In the epidermis of the three species of Phaseolus, there was presence of polyphenols (35 d of pod development) just as in some cells of the external parenchyma that surrounded the sclerenchyma layer, but in a smaller quantity (Figure 4). In P. vulgaris and P. polyanthus, the space occupied by the polyphenols in the cells was small, whereas in P. coccineus the space occupied was greater, although the presence of these compounds was minimal in the three species (Figure 5). In all of the cells of the parenchyma in pods of 50 d of development of P. vulgaris and P. polyanthus, starch grains were observed (Figure 6), but in P. polyanthus, it was concentrated in greater proportion in the cells closer to the sclerenchyma layer, and in P. coccineus the starch was found only in the parenchyma cells near to the sclerenchyma layer (Figure 7). The presence of starch was greater in P. vulgaris than in the other two species. These results coincide with Revé and Brown (1968), who observed that the cells of the external parenchyma are of varied size, having abundant starch grains, chloroplasts and intercellular spaces, and that the internal parenchyma is a tissue without starch or chloroplasts, and few intercellular spaces. CONCLUSIONS es Figura 7. Fotomicrografía de la vaina de P. coccineus a los 50 d de desarrollo mostrando la presencia de almidón (a) cercano a la capa de células de esclerénquima (es); parénquima externo (pe); epidermis (e). Corte transversal. (10X). Figure 7. Photomicrography of the pod of P. coccineus at 50 d of development showing the presence of starch (a) near the layer of sclerenchyma cells (es); external parenchyma (pe); epidermis (e). Transversal cut. (10X). cercanas a la capa de esclerénquima (Figura 7). La presencia de almidón fue mayor en P. vulgaris que en las otras dos especies. Estos resultados coinciden con Revé y Brown (1968) quienes observaron que las células del parénquima externo son de tamaño variado, contienen abundantes granos de almidón, cloroplastos y espacios intercelulares, y que el parénquima interno es un tejido sin almidón ni cloroplastos y escasos espacios intercelulares. In the first 20 d of development, the pod of the three species of Phaseolus presented no differences in their tissue structure; at 25 d the tissues of the pod began to show changes, the dehiscence tissue was differentiated, the hypodermis was thickened and the sclerenchyma layer was lignified. At 50 d after flowering, the pod of P. coccineus was thicker than that of P. vulgaris due to the greater amount of tissues that it is comprised of, principally hypodermis, internal fibers and epidermis. The trichomes were abundant in the first stages of pod development and disappeared as the pod developed, ceasing to be visible at 50 d in the three species. P. vulgaris presented a greater amount of starch in the external parenchyma than the other two species, whereas the presence of polyphenols was minimal in the three species. —End of the English version— HERRERA-FLORES et al. 601 AGROCIENCIA, NOVIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE 2005 CONCLUSIONES LITERATURA CITADA En los primeros 20 d de desarrollo la vaina de las tres especies de Phaseolus no presentó diferencias en la estructura de sus tejidos; a los 25 d los tejidos de la vaina comenzaron a mostrar cambios, se diferenció el tejido de dehiscencia, se engrosó la hipodermis y se lignificó la capa de esclerénquima. A los 50 d después de la floración la vaina de P. coccineus fue más gruesa que la de P. vulgaris por la mayor cantidad de tejidos que la constituyen, principalmente por hipodermis, fibras internas y epidermis. Los tricomas fueron abundantes en las primeras etapas de desarrollo de la vaina y desaparecieron conforme ésta se desarrolló, hasta dejar de ser visibles a los 50 d en las tres especies. P. vulgaris presentó mayor cantidad de almidón en el parénquima externo que las otras dos especies, mientras que la presencia de polifenoles fue mínima en las tres especies. CIAT. 1984. Centro internacional de Agricultura Tropical. Morfología de la planta del frijol común. Guía de estudio. Cali, Colombia. 50 p. Curtis, P. J. 1986. Microtecnia Vegetal. Trillas. México. 106 p. Díaz, M. F. 1990. Crecimiento de la vaina y semillas del frijol. Turrialba 40: 553-561. Esau, K. 1982. Anatomía de las Plantas con Semilla. Editorial Hemisferio Sur S. A. Barcelona, España. 511 p. García, E. 1981. Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación Climática de Koeppen (para adaptarlo a las condiciones de la República Mexicana). 2ª. Edición, UNAM, D.F. 246 p. González E., A., y E. M. Engleman. 1982. Anatomía de la vaina de Phaseolus coccineus. Agrociencia 48: 7-28. Revé, R. M., and M. S. Brown. 1968. Histological development of the green bean pod as related to culinary texture. 2. Structure and composition at edible maturity. J. Food Sci. 33: 326-331. SAS Institute Inc. 1999. Procedures Guide, Version 8. SAS®. 1643 p. Sass, J. E. 1958. Botanical Microtechnique. 3rd. Ed. Iowa State. Univ. Press Ames. Iowa. 228 p. Smartt, J. 1942. Comparative evolution of pulse crops. Euphytica 25: 139-143. 602 VOLUMEN 39, NÚMERO 6