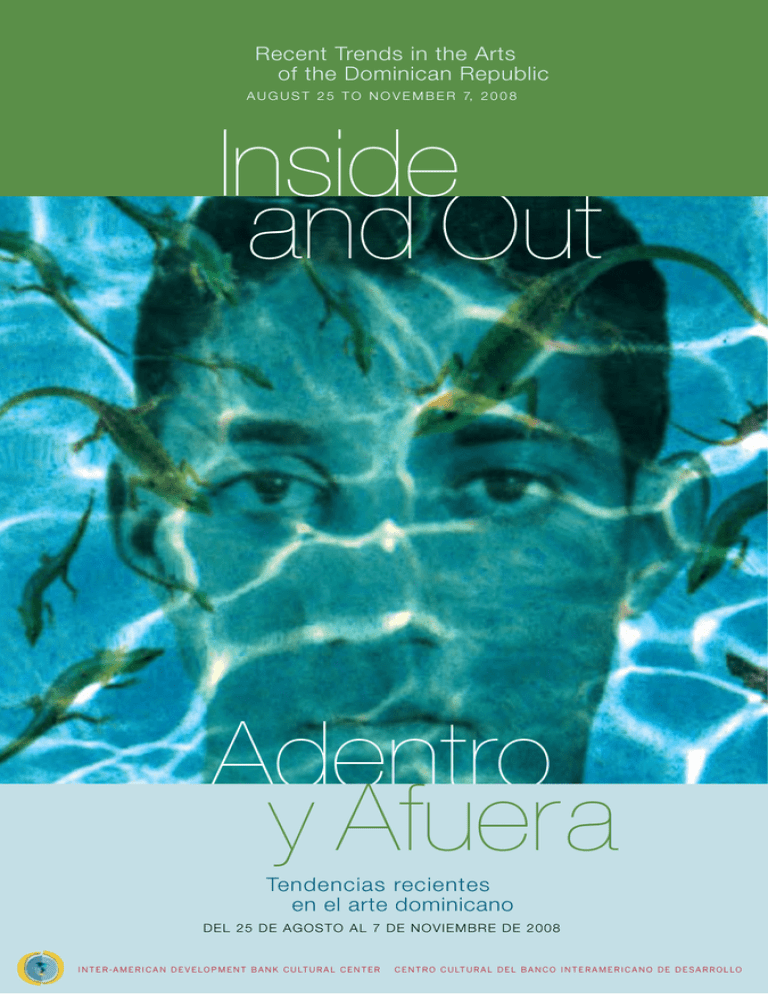

Tendencias recientes en el arte dominicano Recent Trends in the

Anuncio

Recent Trends in the Arts

of the Dominican Republic

A u g u s t 2 5 t o N o v e m b e r 7, 2 0 0 8

Inside

and Out

Adentro

y Afuera

Tendencias recientes

en el arte dominicano

I N T E R - AD

MeElR I2

C5

A NdDeE A

V Egos

LO P M

E Na

T lB A7Nde

K C UNo

LT U

L C Ere

N T Ede

R 2008

to

vRi eAmb

I N T E R -A M E R I C A N D E V E LO P M E N T BA N K C U LT U R A L C E N T E R

C E N T R O C U LT U R A L D E L BA N C O I N T E R A M E R I C A N O D E D E SA R R O L LO

THE INTER-AMERICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK

Luis Alberto Moreno

President

Daniel M. Zelikow

Executive Vice President

Otaviano Canuto

Vice President for Countries

Santiago Levy

Vice President for

Sectors and Knowledge

Manuel Rapoport

Vice President for

Finance and Administration

Steven J. Puig

Vice President for Private Sector

and Non-Sovereign Guaranteed Operations

Pablo Halpern

External Relations Advisor

•

THE CULTURAL CENTER

Félix Ángel

General Coordinator and Curator

Soledad Guerra

Assistant General Coordinator

Anne Vena

Inter-American Concert, Lecture and Film Series Coordinator

Elba Agusti

Cultural Development Program Coordinator

Debra Corrie

IDB Art Collection Management and Conservation Assistant

Mone-Renata Holder

Intern, University of Heriot Watt, UK

Lorena Rebollo del Valle

Intern, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland

Cover: Aquiles: el corazón cayó al mar (Achilles: The Heart Fell into the Sea) • 2007

J U L I O VA L D E Z

Cataloging-in-Publication data provided by the

Inter-American Development Bank

Felipe Herrera Library

Inside and out : recent trends in the arts of the Dominican Republic = adentro y

afuera: tendencias recientes en el arte dominicano.

p. cm.

ISBN: 1-59782-081-4

ISBN: 978-1-59782-081-3

Text by Marianne de Tolentino and Sara Hermann.

Text in English and Spanish.

Exhibition at the Inter-American Development Bank Cultural Center from August 25,

2008 to November 7, 2008.

1. Painting, Dominican—Catalogs. 2. Art—Dominican Republic—Catalogs. 3. Art, Modern—Dominican

Republic—Catalogs. 4. Art, Modern—21st century--Catalogs. I. Tolentino, Marianne de. II. Hermann,

Sara. III. Inter-American Development Bank. IV. IDB Cultural Center. V. Added title.

ND315.D6 I76 2008

759.97293 I76------dc22

Inside and Out

Adentro y Afuera

Recent Trends

in the Arts of the

Dominican Republic

Tendencias

recientes

en el arte

dominicano

0 8 / 2 5 / 0 8 ~ 1 1 / 0 7 / 0 8

1

D E TA I L :

Cabezas llenas de plátanos (Heads Full of Plantains)

RADHAMÉS MEJÍA

2

• 2008

Introduction

The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) is proud to host an exhibition honoring

the Dominican Republic, a Caribbean country with a rich and diverse cultural tradition, and a dynamic contemporary arts scene.

Just as important as the artistic activity in the cities of Santo Domingo, Altos

de Chavón, Santiago de los Caballeros, and Puerto Plata — four of the most

active Dominican cultural enclaves in the island nation, is the presence of Dominican artists outside their country, working in New York, Madrid, and Paris, to

name a few.

In today’s globalized world, the challenges of development are causing fundamental changes in the personalities of the nations in our hemisphere. The region is not marginalized, and neither is it indifferent to such a perception.

It is extremely important to establish an uninterrupted dialogue between citizens of the same nationality and their peers living elsewhere. All countries in

Latin America and the Caribbean may benefit from such an exchange, which

could be mutually enriching for their ongoing efforts to create a better future with

the benefit of the lessons learned.

With this exhibition, in which half of the artists live in the Dominican Republic, and the other half live somewhere else, the IDB encourages such a dialogue

under the umbrella of its Cultural Center. It also celebrates the Dominican artists

for the distinguished position they have achieved for their country at the international level.

Luis Alberto Moreno

PRESIDENT

Inter-American Development Bank

Washington, D.C.

Aproximación (Approximation)

• 2006

FA U S TO O R T I Z

3

D E TA I L :

Después de la siesta (After the Nap)

POLIBIO DÍAZ

4

• 2001-2004

The Advancement

of Dominican Art

For many years the artistic movement in the Dominican Republic was a “best-kept

secret.” Their growing international contributions to contemporary visual arts have

been changing that picture, but may also be characterized by even greater drive, selectivity, and regularity. We could say that of all the islands of the Caribbean, the Dominican Republic is, along with Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Haiti, the country most prolific in regard to modern and contemporary artists. It now boasts over three hundred

painters, sculptors, installation artists, draftsmen, and printmakers, without counting

the ever-growing myriad of photographers, the core of video artists, and a number of

“performance artists.” A good portion of these artists pursue several artistic languages, as is the case with those on display here. However, whereas plastic artists also

tend to do photography, photographers limit themselves to the “writing of light.”

In the 1980s, there was a boom in art shows, in prices, in private and institutional

collections, in the people comprising the latest artistic generation. The decade was characterized by the “demographic explosion” of new names who were particularly distinguished by their creativity, their inquiries, and their experimental temperament. Post

expressionists or postmodernists drew on familiar cultural legacies (Indo-American, African, European) while acknowledging American models.

These artists brought anthropological, ethnic, and social signs and symbols into drawings, paintings, and installations (the most widespread type of artwork), and their combined

categories. They are distinguished by their continual searching and avant-garde language. The

artists on display in the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) gallery are from among

these creators who emerged in the last two decades of the last century.

Boom times tend to be short in art. . . . The last decade of the twentieth century

was cruel to the fortunes of artists, with few exceptions. Creative enthusiasm nevertheless continued, enhanced by something new: incipient international dimension,

in Latin America and the Caribbean and in various countries in Europe. The United

States had begun to welcome the visual arts of the Caribbean with the extensive

group exhibition at the Americas Society Art Gallery in New York in 1996.

The Artists of the Diaspora

With the exception of the United States, and New York in particular, Dominican art-

ists do not emigrate much to other countries in the Hemisphere, and even less to other

Caribbean islands. The exception in the latter case is Puerto Rico, a prosperous land

developed in the field of visual arts and, above all, a gateway to the United States.

When it is said that the increasingly active and firmly established Dominican

5

diaspora has grown, it is in reference to native-born artists who took up residence

in Europe, and primarily in the United States. They are first and also second generation, those whose parents had already left Santo Domingo. By way of exception, they are labeled “the transplanted”—as Sara Hermann called them on the

occasion of a Biennial—and “absent Dominicans,” a term applied to all those

living abroad, regardless of the kind of work they do!

We recall that etymologically “diaspora” means a people scattered beyond

its borders. In art the word has been used more widely during the past thirty

years. From the standpoint of lifestyles and creation, Christine Chivallon defines

it as “the ability to retain unity and an identity despite being uprooted.”

Thus in regard to the visual arts, Dominican artists settled in Europe (Spain,

France, Germany, the Netherlands) or in North America do not express in their work

a depersonalizing mimicry or an appropriation of images, but an enriching renewal.

They preserve their cultural identity and communicate into it multiple dimensions,

utilizing materials, techniques, and technologies, placing them at the service of kindred signs and symbols, freely choosing their affiliations. In fact, “nondisplaced”

native artists may be much more susceptible to outside currents and fashions, in a

desire for originality and being au courant, which does not always prevent plagiarism (whether detected or not!). I share the view of an artist of the diaspora who lives

in Paris, when he says that the issue of Caribbean (and therefore Dominican) art

cannot be addressed without taking artistic diasporas into account. Artists highlight

references to their land of origin or to similar cultures, and some even exploit their

lineage to lend themselves an exotic air for their own success. . . .

The Dominican colony in New York City is huge, around a million people, of all

generations, doing all kinds of work, including several dozen artists. That is where

the artistic diaspora is largest and most solid. The contemporary artists who have

emigrated to the United States or major European cities (Paris, Madrid, Rome, Amsterdam) generally have a strong personality, are young or on the threshold of young

middle age, and have settled there because of family ties (older relatives or spouses),

although not always. If they are part of a first generation of immigrants, they have

regarded immigration as the best, if not the only, way of making themselves known,

apart from learning, subsisting, and disseminating the country’s art, as one of its best

visual artists, a disillusioned traveler, recently told me with a hint of bitterness.

Long stays in places with exceptional means for the development of artistic activities are no doubt a true privilege that is advantageous for the Dominican Republic, the

evolution of its visual arts, and the diffusion of its expressions, and that exercises a great

influence on the nation’s art. Their imprint is obvious, even if those who stayed behind

do not like to admit it.

Immigration may also be driven by an inner discomfort, by the sensation of

creative impasse: the aim will not be to lose oneself but to find oneself, a phenomenon that has been examined by Dominique Berthet1 in connection with

6

l’errance, from a general standpoint. The artist sets out searching for the acceptable place for discovering himself and/or the creative process, both to improve

his or her condition and to find the chance to exhibit his or her work.

With regard to Dominicans who live and work in their country, the impact of

testimonies and environments, habits and behaviors, tastes and objects, resulting

from the diaspora, transmitted particularly through photography,2 is well known.

Investigations into memory and cultural origins have given rise to masterworks,

with their tropical sources of inspiration metaphorized and reinvented depending on the artist’s familial ties. It may be noted that while most diaspora artists do

not intend to return to the land of their birth permanently, they periodically go

back there to recover direct contacts and their deep roots, as well as to attend

specific events.

The overall analysis that I have just sketched is especially relevant to the four

diaspora artists participating in this exhibition, in accordance with their respective circumstances.

A Contemporary Art on the Move

Art exhibitions by Dominican artists in New York, Washington, Chicago, and Miami

are undoubtedly increasingly common. At the start of the third millennium having

shows abroad and participating in international events is no longer utopian. Among

other auspicious signs, it should be noted that Santo Domingo is a gathering point for

the Caribbean, because this city has hosted the Biennial of Art of the Caribbean and

Central America five times, thereby helping to strengthen ties between artists and

critics of the region, who generally attend all the international competitions open to

the so-called magic arc of islands. In 2003 the Eduardo León Jimenes Cultural Center

was created in the Dominican city of Santiago de los Caballeros, a source of pride for

Dominican art and culture. In late September 2006 El Museo del Barrio in New York

City inaugurated the wonderful exhibit “Que no me quiten lo Pinta’o!” [“Don’t let

them take away what’s painted!”] showcasing art inspired by the merengue, a popular Dominican dance. A multimedia exhibit of radical contemporary art opened in

the Brooklyn Museum in 2007. The exhibition “Inside and Out: Recent Trends in the

Arts of the Dominican Republic” was inaugurated in Washington in August 2008 at

the IDB Cultural Center. And I have limited myself here solely to group exhibitions.

The numerous young Dominican artists from the last two decades of the

twentieth century constituted a powerful force, as they diversified their modes

of expression. Installation art flourished quickly, the end of the century dominating as a renewing category, very soon integrating image in movement. Doing

installation art means feeling less subjected to the academic aegis, mixing archaism and sophistication, Caribbean spirit and planetary vision. The magic of the

tropics and the fantastic imaginary find a terrain of choice, often externally and

internally critical.

7

Reeducando a Mónica V (Reeducating Monica V)

• 2008

MÓNICA FERRERAS

Contemporary art, full of boldness, questioning, and uncertainties as well,

is confronting previous currents and generations, and the incipient twenty-first

century confirms the triumph of photography as art and the preoccupations of

video. Photographers from Santiago de los Caballeros, the cradle of Dominican

photography since the 1960s, have developed a passion for topics that continually regenerate, by a magic redeployment of their visions, a way of questioning

the viewer about the mestizo cultural legacy. Despite changes and “subversive”

influences, an aesthetic tradition of balance, even of harmonies, in color and

composition, has remained in place.

If we look for common denominators in painting, which has continued to

dominate the artistic scene (even though some wanted to announce its death),

when encompassed in a single view, we note the subtle song of color, the energy

and subtlety of brushstroke, the impasto or transparency of pigment (oil, acrylic,

8

mineral mixtures). Its expression continues alternating between baroque and

contained, organic and constructivist forms, while organizing space. We could

speak of real, imaginary, and introspective poetics. And figurativeness always

surpasses abstract treatments, since this is not some ancient division, but rather

the two are indicators for interpreting works that are certainly presented here.

Drawing is brilliant and varied, as demonstrated by virtuoso draftsmen, and

their line is made with any medium, whether traditional or not, including embroidery. Printmaking is almost in its death throes, victim of prejudices, ignorance,

and preference for the unique work . . . but the myth of the phoenix allows one

to harbor hopes of yet another flight. Another category in crisis is the scarcely

present sculpture, which is caught between the tradition of direct carving and

an art of rupture that makes use of plastics, resins, and recycled materials, or the

modified ready-made.

Myths and rites, religiosity, syncretism, and magic, dreams and anxieties, sensuality and eroticism, are still fruitful sources of inspiration, eleven years after the

exhibit “Mystery and Mysticism in Dominican Art,” presented at the IDB Cultural

Center. Recently, however, environmental defense, the disadvantageous condition of

women and children, the denouncing of violence, the abuse of the weak, the problems of illegal immigration and displacements, the Caribbean diaspora in the United

States, the tragedy of AIDS, the collapse of peace, and the arms race have all become

part of Dominican art. Social commitment, which so inspired the Dominican visual

arts in the 1960s, has made a comeback, leaving behind “art for art’s sake,” and has

directed its attention to the crossroads of the city.

The big difference is that the contemporary artist, caught up in globalization

and instant communications, is concerned with expressing national and world

problems alike, and the latter increasingly have greater impact than the former.

In brief, it is obvious that in the first decade of the twenty-first century, the Dominican visual arts manifest an accentuated diversification and, indifferent to

how they are defined, are deployed freely and openly. That is proven by the eight

artists grouped together in this exhibition.

Marianne de Tolentino

ART CRITIC

Member, Board of Directors,

International Association of Art Critics,

and Director, Cariforum Cultural Center

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

1-Dominique Berthet, Figures de l’errance

(Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007).

2-Diaspora: identité plurielle, ed. Christine

Eyene and Christine Sitchet (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2008).

9

DETAIL:

Coseré mi corazón en el tuyo (I Will Sew My Heart to Yours)

I N É S TO L E N T I N O

10

• 2008

Eight Ways of

Seeing, Eight Ways

of Entering and

Leaving

It seems like a good idea today to present some entryways into the variety of artistic

discourses produced in the Dominican Republic. The exhibition “Inside and Out:

Recent Trends in the Arts of the Dominican Republic” approaches these matters

from a variety of perspectives. Its very breadth is what makes it rich. By exploring

how much there is or is not of what has been conventionally called or recognized

as Dominican art, one is pointing precisely at that diversity. Challenging or, on the

contrary, being reconciled to what has been inherited or imposed from the standpoint of expectations that people have regarding the art of the region situates the

artists gathered by this show in a privileged position. It is likely that they do not

share the way they do their art, but in some instances they share starting points,

focuses, or strategies when the time comes to produce. One of these is the relationship that they establish between their private being and their public existence.

Polarities between private and public could be transferred to the Dominican terrain

as the possible antagonisms and dichotomies existing between inside and outside.

Much of the work included in this exhibit alludes, in one way or another, to being

inside or being outside, it speaks of being inside or being outside. . . . Such antagonisms and concurrences are quite relevant today, at the confluence of the public

and private, forced by the mass media, “reality” TV, and even computer hacking

processes that expose our lives to whoever wants to look.

There are many ways to be inside or outside, most of them for entering and

leaving. Here are only eight.

Outside

I think, with migration, when we come to a new country, we all come with fragments. When you leave, you take what you can—you take some pictures, you take your

stories, you take your memories, and the rest you feel like you can get better, and more

of, in the other place. You can get better apples, you can get better plantains. But your

memories, you can’t get better memories. They just stay.“

— Edwige Danticat3

11

Brother and Plátanos (Hermano y plátanos)

J U L I O VA L D E Z

12

• 20 05

In his photography Fausto Ortiz speaks to us from the standpoint of migration and its

impact on the space that produces it and welcomes it and on the people who

move away. Although this focus starts from the weight of these processes taking

place in his own familiar environment, in his photography Ortiz directs his efforts

at the migration that takes place between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The

relationship of these two countries is asymmetrical and unbalanced in almost all

respects, and it therefore produces consequences of a social nature. The individual who migrates, in most cases for survival and economic reasons, becomes

a stranger in the new space. The “invisibility” of such individuals is what Ortiz

portrays: “the shadow . . . represents absence, I let myself play with identity,

which is like a myth, I seek the stories that give meaning to this identity.” Hence

shadow is nonexistence, but paradoxically it is also imprint, existence. That is

visible in his work Aproximación (Approximation) (2006), in which the passing

shadow is imposed transitorily on the walls and their own stories.

Julio Valdez, for his part, deals with identity and existential issues in his paintings.

Having personally experienced migration from island to “island” (from the Dominican Republic to Manhattan) gives him a special aptitude for dialoguing from his canvases and papers about his identity: “Personal circumstances, as someone who has

lived inside the island and now lives outside of it, allow me to keep exploring myself,

building myself, with sharper perception. Horizons were expanded. Thus, the social

drama of migrations and exile in the Caribbean also leaks out of my inner core.” His

series in which the sea plays the leading role is intriguing and reflective. Even more

so is his allusion, in the title of one of his works, to “the accursed circumstance . .

. of water on all sides,” as the wonderful Cuban writer Virgilio Piñera expressed it

in La isla en peso (1943). The symbols and metaphors used by Valdez in La maldita

circunstancia (Accursed Circumstance) (2007) are defined by the very multiplicity of

readings, “from the local (internal) to the universal (external) and thus the sea/water

is what unites us (internally) and separates us (mentally, in terms of temperament,

and emotionally) from the others, from what is ‘outside.’” The idea of immersion has

become very important in so-called virtual reality inasmuch as its visual paradigm

means that the observer is inside the world he is observing. Hence, the figures (he

himself, his brother, his acquaintance) are immersed in the sea, and at the same time

surrounded by it. The sea is here more extensive (as if it were possible); it is water.

It was also Piñera who spoke of the plantain (“musa paradisiaca”) from the island.4

Valdez utilizes it like wallpaper to leave the imprint of the portrait. Thus, the face is

as constant as the reference to this very fruit, which is so common and representative

of Dominican culture.

A painter and draftsman by calling and choice, Gerard Ellis establishes an interesting dichotomy between the practice of painting and social critique. His pictorial

work is highly expressive and vigorous for those who directly or indirectly participate

in the multiple strata of the contexts of which this artist speaks. The violence, cor-

13

ruption, and lack of willpower characteristic of our times and everything that reveals

human stupidity are central topics of his meticulous pictorial work. There is a studied

connection and interdependence between what is his work and what constitutes

his life experiences, which translates into a certain underlying politicization of life’s

experience. His work reintroduces issues as to how a gaze articulated around reality can at the same time shape areas of reflection in relation to each individual’s life

experience . . . and conceal the most absolute rebellion. His are pieces that lead us

to those delicious territories of sarcasm and irony that this artist knows how to create.

Good Companion (2007) and Winter Wonderland (2008) are characteristic works of

this play of words and images in which not everything is said but is indeed suggested.

Mar bravo (Rough Sea) (2008), on the other hand, testifies to the act of creating,

the creative process on which Ellis has embarked. Self-referential and sometimes

autobiographical, it presents to us the creative and destructive act of the painter on

a sheet of paper while his skeleton is covered with fish. In this blank space, akin to

pages in children’s books, there is an emotional weight that is less sarcastic and more

analytical of the particularities of his activity.

A strange picture, printed in a box in a nationally circulated newspaper, was

something that caused widespread concern: “East Santo Domingo. A black BMW

SUV with no one in it was dumped into the bottom of the Caribbean for no apparent

reason. The BMW was discovered underwater by a resident of the area who sounded

the alarm.” This intriguing and strange text was for Limber Vilorio the driving force

behind a series of works, bodies of work, and hundreds of hours of ruminations. The

absurd and tantalizing event became a logical sequence of all his previous discursive

lines. Through his gaze, the city and its inhabitants, as well as its constituent elements

(tangible or not), had adopted an emotional dimension that spoke of artificial, chaotic, catastrophic, apocalyptic spaces . . . in the same way in which Santo Domingo

was being transformed before his eyes. This kind of urban obsession led Vilorio to

rescue the prohibited and unnamable spaces of the city, to embody the condemnation and the sorrow of passing through it. Under his gaze there appear myth,

signs, marginalization, violence, and the private lives that go passing through public

places. I once said that through this set of works Vilorio confronts a society that feels

an absolute fascination with the automobile as a status symbol and something that

arouses passions. In the artist’s view, the power of the image, in works like Ahogado

en su gasolina (Drowned in Its Own Gasoline) (2004), Vértigo (Vertigo) (2004), and

A la deriva (Adrift) (2006), lies “in its destruction (that of the car).” The disappearance

of the automobile (thus . . . generically) is, in his own words, “the liberation, the triumph of the ego over the collective superego.”

Finally, the work of Radhamés Mejía is connected to the Dominican Republic, his

homeland, through varied symbolic devices, ranging from the pictographs, petroglyphs, and geometrical system of the native Taino Indians, to those associated with

the current everyday life of Dominicans. Mejía spontaneously speaks of his islander

14

Reeducando a Mónica III (Reeducating Monica III)

• 2008

MÓNICA FERRERAS

self out of the collective memory, the music, the dance, and the habits that make up

an identity forever being built. In Cabezas llenas de plátanos (Heads Full of Plantains,

2008), he divides the work into three fundamental planes, the bottom of which is this

Taino-style mnemotechnic device, rising to the faces in profile, which are crowned

by plantains. The piece is completed at the very top by some shoes with springs

that allude to the movement, the displacement, and the nomadism of the Dominican self. Las boquitas o la pomme (The Hors d’Oeuvres or the Apple) (2008) and

Posesión ritual (Ritual Possession) (2008) strive for a more visceral and emotional tie

to the Afro-Caribbean, also from the perspective of the symbolic, geometrical, and

fragmented aspects of the islander condition. Santiago Villa Chiappe thought that

Antonio Benítez Rojo “conceives of the Caribbean as a nexus, and at the same time

as a dissemination. Nexus because it is a point of union between different worlds, an

encounter of histories that create an imagined community, a cultural ‘universe’ and

a geography. Dissemination, because the Caribbean is a flow of signifiers.” And it is

precisely to these nexuses and signifiers and that encounter of histories that Mejía

refers when he confronts color with geometry, and the symbol with its essence.

Inside

Polibio Díaz is a photographer who in his career has evaluated the contradictions and

relationships of the two categories, inside and outside, from multiple perspectives.

In laying out the depth of the conscious act of the photographer in revealing these

polarities, he had already made it clear that the production of images in his series

Interiors (2001–2004) is conscious of itself, of the tools that build it, of the language

15

C.A.E. Cuerpo, alma y espíritu (Body, Soul and Spirit)

• 2005

MÓNICA FERRERAS

that can be articulated by means of it, and of the perceptive mechanisms that allow a

viewer to receive it and be able to interpret by relating it to his or her own experience

(that of the subject and that of the photographer). Díaz provides a shrewd impression

of contemporary Dominican life through a perspective from “within.” To do so he

draws on the furnishings and household paraphernalia of Dominicans, creating an

exuberant although paradoxically serene coloring, with interesting observations on

the daily life and memory of those who dwell in these spaces. His interiors illustrate

an attitude of contemporary society based on the inner nucleus of the dwelling. Conscious of the influence of consumer culture and of growing materialism, he attempts

to record in his photography the scenes to which these forces lead. Advertising, the

mass media (represented by TV sets and radios), the iconic and transcendent images

of popular religiosity, and flowers made of plastic all start their journey to the sacred

during these frozen moments.

Inés Tolentino is continually renewing herself. Her paintings, drawings, and col-

lages are a reflective reference to her own life story . . . and with her own, that of

women in general. Her most recent body of work guides us to understand body

memory as a place of confluence and paradoxical conflict. Memory, her memory

embodied through the “noble” act of embroidery, reconfigures the categories of the

feminine and of representation, from her own imaginaries to those she considers collective, metaphors of place and rituals, beliefs, and labors. From the outset, Tejiendo

mi historia (Weaving My Story) (2008) provides us with this idea of the act of embroidery as a gesture of intimate references, whether domestically or in the obsessive

passion for adorning and beautifying. So, how do these stitches adorn? They do so

with simple and plain symbols that take us to war, sex, harmless dialogues, animated

cartoons, and even the Sacred Heart of Jesus. These references, which in appearance look naïve, gradually build up a discourse on the structures and schemes that

“organize” the life of women in our societies. Likewise Hilos de vida (Threads of Life)

(2008) constructs a story of violence and death that, even though its author appropriates it from the title, could well constitute the story of thousands of women assaulted

and sacrificed by domestic violence and armed conflicts worldwide.

16

Mónica Ferreras calls herself a Jungian, and the ideas of Carl Jung appear increas-

ingly in her work. Her fundamentally autobiographical paintings reflect her process

of individuation (the way, as defined by Jung, that each of us comes to be what he or

she inherently and potentially is), through which she proposes to us a labyrinth that

symbolizes the journey to being. From these pieces full of organic (amoebas, cells,

DNA chains) and somewhat labyrinthine forms, Ferreras presents us with the complexity of the psychological world (the intricacies of the conscious and subconscious

of the individual), instinctively transferred to canvas. Her way of introducing it into

this body of work starts from a life experience, a metaphor of her life as an individual

and of her life as a social being. Reeducando a Mónica (Reeducating Monica) (2008)

is a series of paintings that reflect this discursive line out of a semantic density based

on analytic theories about the human being and his or her personality. Her video

C.A.E. Cuerpo, alma y espíritu (Body, Soul and Spirit) (2005) shows us on the first

and sole plane a scene of three women in constant movement who act out certain

rites and functions that, it is understood, are theirs within the (literal) framework of a

domestic setting. In doing so, the artist starts from the trinity established by the body,

the soul, and the spirit as compositional basis. This vision, associated with the deconstruction of social representations of woman in society, questions viewers about the

expectations they have regarding what is happening on the screen.

Significant shows have taken place outside of the Caribbean that include projections of Dominicans visually and in terms of meaning—some with more substance

than others, some with fewer prejudices than others. Nevertheless, if something transcends these efforts to organize a way of seeing or energize a vision, it is precisely the

fact that interactions are established between artists, institutions, and curators, and

in some fashion discourses are contaminated so as to allow for interpretations that

emerge from the connections suggested by these interactions. On that basis, movements of opening and dialogue may spread out between these connections, making

possible a new dynamic, that which has been and will be determined and laid out

by the producers of meaning themselves.

Sara Hermann

ADVISOR ON VISUAL ARTS

Eduardo León Jimenes Cultural Center

Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic

3-Edwige, Danticat. “A Conversation with Edwige Danticat:

Interview with Eleanor Wachtel,” 2000.

4-Fragrance can rip off the masks of civilization;

it knows that man and woman will be sinless in the plantain grove.

Musa paradisiaca, protect the lovers! The world need not

be won in order to be enjoyed, two bodies in the plantain

grove are worth as much as the first couple, that odious

couple that served to mark off the separation.

Musa paradisiaca, protect the lovers!

(Virgilio Piñera, La isla en peso, 1943)

17

DETAIL:

Las boquitas o la pomme (The Hors d’Oeuvres or the Apple)

RADHAMÉS MEJÍA

18

• 2008

Introducción

El Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID) se enorgullece de presentar una ex-

posición en homenaje a la República Dominicana, país del Caribe que alberga una

rica y diversa tradición cultural y cuya escena artística contemporánea se caracteriza

por su gran dinamismo.

La presencia de los artistas dominicanos fuera de su país –en Nueva York,

Madrid y París, por nombrar sólo algunos de los lugares donde trabajan– es tan

importante como las actividades artísticas que se desarrollan en las ciudades

de Santo Domingo, Altos de Chavón, Santiago de los Caballeros y Puerto Plata,

cuatro de los enclaves culturales más efervescentes de la nación isleña.

En el mundo globalizado de hoy, los desafíos que plantea el desarrollo producen cambios fundamentales en la personalidad de cada nación de nuestro

hemisferio. La Región no está marginada ni es indiferente a tal percepción.

El establecimiento de un diálogo ininterrumpido entre los ciudadanos connacionales y sus pares que viven en otros lugares reviste suma importancia. Todos los países de

América Latina y el Caribe están en condiciones de beneficiarse con intercambios de

este tipo, que podrían resultar mutuamente enriquecedores en el marco de su actual

esfuerzo por crear un futuro mejor con la ventaja de las lecciones ya aprendidas.

Con esta exposición, en la cual la mitad de las obras pertenecen a artistas que viven en la República Dominicana, y la otra mitad, a artistas dominicanos que viven en

otros países, el BID alienta a que se establezca un diálogo como el que describo aquí

en el marco de su Centro Cultural. También celebra a los artistas dominicanos por la

posición distinguida que han logrado para su país en el ámbito internacional.

Luis Alberto Moreno

PRESIDENTE

Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo

Washington, D.C.

Sombras pasajeras (Passing Shadows)

• 2005

FA U S TO O R T I Z

19

D E TA I L :

Después de la siesta (After the Nap)

POLIBIO DÍAZ

20

• 2001-2004

El avance del arte

dominicano

En la República Dominicana, el movimiento artístico fue, durante muchos años, el

“secreto mejor guardado”. La creciente proyección internacional de los valores de

la plástica actual ha ido modificando dicho panorama, pero esta difusión puede

marcarse aun con mayor empuje, selectividad y regularidad. Podríamos afirmar que,

junto con Cuba, Puerto Rico y Haití, la República Dominicana es, en toda la región

del Caribe insular, el país más fecundo en artistas modernos y contemporáneos. Se

enorgullece actualmente de sus más de trescientos pintores, escultores, instaladores,

dibujantes, grabadores, sin contar la legión de fotógrafos en permanente crecimiento, el núcleo de video artistas y unos cuantos “performanceros”. Buena parte de ellos

cultivan varios lenguajes artísticos, como es el caso de quienes exponen en esta

muestra. Ahora bien: si los creadores plásticos también suelen hacer fotografía, los

fotógrafos se limitan a la “escritura de la luz”.

En los años ochenta se produjo un boom de las exposiciones, de los precios, de

las colecciones particulares e institucionales, de un colectivo integrado por la última

generación. La “explosión demográfica” de nombres nuevos caracterizó a la década, y ellos se distinguieron especialmente por su creatividad, sus investigaciones,

su naturaleza experimental. Posexpresionistas o posmodernos, activaron, de manera

estudiada y con impronta propia, la consabida herencia cultural —indoamericana,

africana, europea—, sin olvidar la irrupción de modelos norteamericanos.

Esos artistas llevaron signos y símbolos, antropológicos, étnicos, sociales, a dibujos,

pinturas e instalaciones —el tipo de obra de mayor auge— y categorías mixtas. Ellos se

distinguen por la búsqueda permanente y un lenguaje de avanzada. De estos creadores,

aquellos que surgieron en las dos últimas décadas del siglo pasado son los que exponen

en la galería del Centro Cultural del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID).

Los tiempos de bonanza suelen ser breves para el arte... El último decenio del

siglo XX fue cruel en cuanto a la holgura de los artistas, salvo pocas excepciones.

No obstante, el entusiasmo creador prosiguió, reforzado por un elemento nuevo:

la incipiente proyección internacional, en América Latina y el Caribe y en distintos

países de Europa. Estados Unidos había empezado a acoger a nuestra plástica

con la extensa muestra colectiva de la American Society en 1996.

Los artistas de la diáspora

Con excepción de Estados Unidos, y de Nueva York en particular, los artistas domini-

canos raramente emigran hacia otros países del continente, y menos aún del Caribe

insular, salvo Puerto Rico, territorio próspero y desarrollado en el campo de las artes

21

C.A.E. Cuerpo, alma y espíritu (Body, Soul and Spirit)

• 2005

MÓNICA FERRERAS

visuales y, sobre todo, puerta de entrada a Estados Unidos.

Cuando se afirma que la diáspora dominicana ha ido creciendo, cada vez

más activa y firme, es con referencia a los artistas criollos que se establecieron

en Europa y principalmente en Estados Unidos, que constituyen la primera generación e incluso la segunda— ya habían salido de Santo Domingo sus padres—

Se los designa excepcionalmente “transterrados”— como los denominó Sara

Hermann en ocasión de una bienal—y “dominicanos ausentes”, ¡expresión que

se aplica a todos los que residen en el exterior, sea cual fuere su oficio!

Recordemos que la diáspora, según la etimología, hace referencia a un

pueblo dispersado más allá de sus fronteras; y en arte, esta palabra ha alcanzado

mayor difusión en los últimos treinta años. Desde el punto de vista de los modos

de vida y de la creación, Christine Chivallon la define como “la capacidad de

mantener la unidad y una identidad más allá del desarraigo”.

Asimismo, en las artes visuales, el artista dominicano instalado en Europa —España, Francia, Alemania, Holanda— o en Norteamérica no expresa en su obra un

mimetismo despersonalizante o una apropiación de imágenes, sino una renovación

enriquecedora. Él conserva su identidad cultural y le comunica múltiples dimensiones, aprovechando materiales, técnicas y tecnologías, poniéndolas al servicio de

signos y símbolos afines, eligiendo libremente sus afiliaciones. Más aún: el artista

criollo “no deslocalizado” puede ser mucho más permeable a corrientes y modas

externas, en un deseo de originalidad y actualización ¡que no siempre evita el plagio, detectado o no! Compartimos la opinión de un artista de la diáspora residente

en París cuando plantea que no se puede abordar el tema del arte caribeño, y por

tanto del dominicano, sin tomar en cuenta las diásporas artísticas. Los artistas exaltan las referencias a la tierra de origen o a culturas similares, y no falta quien explote

aun su estirpe como un factor de exotismo y éxito…

La colonia dominicana en la ciudad de Nueva York es muy grande, ya que

ronda el millón de habitantes, de todas las generaciones y clases de labores; y

entre ellos hay varias decenas de artistas: es allí donde la diáspora artística es la

más numerosa y sólida. Los artistas contemporáneos que han emigrado a Estados

22

Unidos o a metrópolis europeas —París, Madrid, Roma, Ámsterdam— poseen,

en general, una fuerte personalidad, son jóvenes o están en el umbral de su

joven madurez y se han instalado allí porque tienen vínculos familiares —ascendentes o cónyuges—, aunque no en todos los casos. Si forman parte de una

primera generación de migrantes, han considerado la migración como la mejor,

sino la única, forma de darse a conocer, aparte de aprender, subsistir y difundir

el arte del país, como nos lo decía en fecha reciente uno de nuestros mejores

artistas plásticos, viajero desilusionado, con un dejo de amargura.

No caben dudas de que las estadías prolongadas en lugares que cuentan con

medios excepcionales para el desarrollo de actividades constituyen un verdadero privilegio, que no puede sino ser provechoso para la República Dominicana,

la evolución de sus artes visuales y la difusión de sus expresiones, y que ejerce

gran influencia sobre el arte nacional. Aunque para muchos no es grato admitir

esto, su impronta se advierte en aquellos que se quedaron.

La migración puede estar impulsada también por un desajuste interior, por la

sensación de estancamiento creativo: el objetivo no será perderse, sino encontrarse, un fenómeno que ha sido analizado por Dominique Berthet1 a propósito

de l’errance, desde un enfoque general. El artista sale en busca del lugar acceptable para el descubrimiento de sí mismo y/o del acontecer creativo, tanto como

para mejorar sus circunstancias y hallar la oportunidad de proyectar su obra.

En la temática de los propios artistas dominicanos que viven y trabajan en su

país es notorio el impacto de testimonios y ambientes, hábitos y conductas, gustos y objetos, que son producto de la diáspora, particularmente transmitidos por

la fotografía.2 En cuanto a las investigaciones sobre la memoria y los orígenes culturales, ellas han dado origen a trabajos magistrales, con sus fuentes tropicales de

inspiración, metaforizadas y reinventadas según la filiación del autor. Cabe señalar

que si bien la mayoría de los artistas de la diáspora no tienen en vista el retorno

definitivo al suelo natal, periódicamente vuelven a él para recuperar los contactos

directos y sus raíces profundas, además de concurrir a eventos puntuales.

El análisis global que acabamos de esbozar puede muy bien aplicarse a los

cuatro artistas de la diáspora que participan en esta exposición, de acuerdo con

sus circunstancias respectivas.

Un arte contemporáneo en movimiento

Indudablemente, cada vez son más frecuentes las exposiciones en Nueva York,

Washington, Chicago y Miami. En los inicios del tercer milenio, exponer en el

exterior y participar en eventos internacionales ya no es una utopía. Entre las

perspectivas auspiciosas, cabe señalar que Santo Domingo constituye un punto

de encuentro para la región caribeña, pues en esa ciudad se han celebrado

cinco ediciones de la Bienal de Arte del Caribe y Centroamérica, contribuyendo así a estrechar los contactos entre artistas y críticos de la región, cuya

23

presencia es habitual en todas las justas internacionales abiertas al llamado

“arco mágico” de islas. En la ciudad de Santiago de los Caballeros se creó

en 2003 el Centro Cultural Eduardo León Jimenes, orgullo para la cultura y

el arte dominicanos. A fines de septiembre de 2006, el Museo del Barrio, de

la ciudad de Nueva York, inauguró el magnífico conjunto plástico Que no

me quiten lo Pinta’o!, inspirado en el merengue, danza popular dominicana.

En 2007 se llevó a cabo una exposición multimedia de arte contemporáneo

radical en el Museo de Brooklyn. En agosto de 2008, en la ciudad de Washington, D.C., se abre en el Centro Cultural del BID la exposición titulada

Adentro y afuera: tendencias recientes en el arte dominicano. Y nos hemos

circunscripto exclusivamente a eventos colectivos.

Los numerosos artistas jóvenes constituyeron una poderosa fuerza, al diversificar los modos de expresión. La instalación floreció rápidamente, dominando

el ocaso del siglo como categoría renovadora e integrando muy pronto la imagen

en movimiento. Instalar significa sentirse menos sujeto a la égida académica,

mezclando arcaísmo y sofisticación, espíritu caribeño y visión planetaria. La

magia del trópico y el imaginario fantástico encuentran terreno de elección, a

menudo crítico exterior e interiormente.

El arte contemporáneo, inmerso en audacias, cuestionamientos e incertidumbres también, se confronta con las corrientes y generaciones anteriores, y el incipiente siglo XXI confirma el triunfo de la fotografía como

arte y las inquietudes del video. Los fotógrafos de Santiago de los Caballeros,

cuna de la fotografía dominicana desde los años sesenta, se han apasionado

por temas que regeneran continuamente, por un mágico redespliegue de sus

visiones, una manera de interpelar al espectador acerca del legado cultural

mestizo. A pesar de los cambios e influjos “subversivos”, una tradición estética de equilibrio, de armonías incluso, en el color y en la composición, se

ha mantenido vigente.

Si buscamos denominadores comunes en la pintura, que no ha dejado de dominar la escena artística —aunque se pretendió decretar su

muerte—, al abarcarla en una sola mirada es posible advertir el canto

sutil del color, la energía y la sutileza de la pincelada, la untuosidad

o la transparencia del pigmento —óleo, acrílico, mezclas minerales—.

Su expresión continúa alternando las formas barrocas y contenidas,

orgánicas y constructivistas, pero ordenando el espacio. Podríamos

hablar de poética real, imaginaria e introspectiva. Y siempre la figuración sobrepasa las intervenciones abstractas, tratándose no de una

escisión añeja, sino de indicadores para la lectura de obras, por cierto,

aquí presentadas.

El dibujo es brillante y variado, como lo demuestran dibujantes virtuosos, y

su línea es instrumentada por cualquier medio, tradicional o no, incluyendo el

24

bordado. El grabado casi agoniza, víctima de los prejuicios, la ignorancia y el

favor de la obra única… pero el mito del Ave Fénix permite abrigar esperanzas.

Otra categoría en crisis es la escasa escultura, que se debate entre la tradición de

la talla directa y un arte de ruptura, recurriendo a plásticos, resinas y materiales

pobres o al ready made intervenido.

Mitos y ritos, religiosidad, sincretismo y magia, sueños y angustias, sensualidad y erotismo, continúan siendo fecundas fuentes de inspiración, once

años después de la exposición Misterio y misticismo en el arte dominicano,

presentada en el Centro Cultural del BID. Ahora bien: recientemente, la defensa de la ecología, la condición desfavorable de la mujer y los niños, la

denuncia de la violencia, los abusos contra los débiles, los problemas de la

migración y los desplazamientos ilegales, la diáspora caribeña en Estados

Unidos de América, el drama del sida, la quiebra de la paz y la carrera armamentista, se han instalado en el arte dominicano. El compromiso social,

que tanto inspiró a la plástica dominicana en los años sesenta, ha vuelto a

manifestarse, dejando atrás “el arte por el arte”, y se ha volcado hacia las

encrucijadas de la ciudad.

La gran diferencia es que el artista contemporáneo, inmerso en la globalización y en la comunicación instantánea, se preocupa de igual modo por

expresar problemas nacionales y mundiales, y estos últimos tienen cada vez

mayor repercusión que los primeros. En pocas palabras, es evidente que las

artes visuales dominicanas, en la primera década del siglo XXI, hacen gala

de una acentuada diversificación e, indiferentes a una definición, se despliegan libre y abiertamente. Los ocho artistas reunidos en esta exposición así lo

demuestran.

Marianne de Tolentino

CRÍTICA DE ARTE

Miembro del Consejo de Administración

de la Asociación Internacional de Críticos de Arte

Directora del Centro Cultural Cariforo

Santo Domingo, República Dominicana

1-Berthet, Dominique. Figures de l’errance.

Ed. L’Harmattan. París, 2007.

2-Diaspora: identitplurielle. Obra colectiva

bajo la dirección de Christine Eyene y

Christine Sitchet. Ed. L’Harmattan.

París, 2008.

25

DETAIL:

Tejiendo mi historia (Weaving My Story)

I N É S TO L E N T I N O

26

• 2008

Ocho maneras de

ver. Ocho maneras

de entrar y salir

Hoy parece oportuno plantear algunas vías de acceso hacia la heterogeneidad

de los discursos artísticos que se producen en la República Dominicana. La

exposición Adentro y afuera: tendencias recientes en el arte dominicano se acerca

a estos planteamientos desde una variedad de perspectivas. Su propia amplitud

le confiere la riqueza. Al explorar cuánto hay o no hay de lo que convencionalmente se ha llamado o reconocido como arte dominicano, se está apuntando

precisamente a esa diversidad. Desafiar o, por lo contrario, reconciliarse con lo

heredado o lo impuesto desde el punto de vista de las expectativas que se tiene

sobre el arte de la región ubica a los artistas reunidos por la muestra en una

posición privilegiada. Es probable que ellos no compartan formas de hacer, pero

en algunos casos comparten puntos de partida, enfoques y estrategias a la hora

de producir. Una de estas es la relación que establecen con su ser privado y su

existir público. Esas polaridades entre lo privado y lo público podrían trasladarse

al territorio dominicano como los posibles antagonismos y dicotomías que hay

entre adentro y afuera. Gran parte de la obra que integra este conjunto expositivo

alude, de una manera u otra, a estar adentro o estar afuera, habla de estar adentro o estar afuera… Antagonismos o concurrencias que hoy, en la confluencia de

lo público y lo privado, obligada por los medios masivos de comunicación, la TV

“real” y hasta los procesos de exposición —“hackeo” que despliegan nuestras

vidas a quien quiera ver—, tienen bastante pertinencia.

Hay muchas maneras de estar adentro o afuera; las más, para entrar y salir.

Estas son sólo ocho.

Afuera

En cuanto a migración, pienso que cuando llegamos a un nuevo país, todos

llegamos con fragmentos. En cambio cuando salimos, llevamos lo que podemos

—llevamos fotos, historias, memorias, y por lo demás uno siente que puede

mejorar; y más aún, en el otro lugar. Uno puede conseguir mejores manzanas,

obtener mejores plátanos. Pero recuerdos, uno no puede adquirir mejores recuerdos.

Estos simplemente se quedan.

— Edwige Danticat3

27

Ahogado en su gasolina (Drowned in Its Own Gasoline)

• 2004

L I M B E R V I LO R I O

Fausto Ortiz nos habla en su fotografía desde la perspectiva del fenómeno migratorio y

su impacto en el espacio que lo produce y en el que lo acoge y en las personas que se

trasiegan. Un enfoque que, aun cuando parte del peso de estos procesos en su propio

entorno familiar, Ortiz los dirige en su producción fotográfica, fundamentalmente, al

fenómeno migratorio que se produce entre Haití y la República Dominicana. La relación

entre estos dos países en casi todos los aspectos es asimétrica, desequilibrada, y tiene,

por ende, consecuencias de carácter social. El individuo que migra, en la mayoría de los

casos por razones económicas y de supervivencia, se convierte, en el nuevo espacio, en

un ente ajeno. La “invisibilidad” de estos personajes es la que Ortiz retrata: “la sombra

(…) representa la ausencia, me permite jugar con la identidad, que es como un mito;

busco las historias que le dan sentido a esta identidad”. De ahí que la sombra es inexistencia, pero paradójicamente también es impronta, existencia. Esto es visible en su pieza

Aproximación (2006), en la cual la sombra, transeúnte, se impone transitoriamente a las

paredes y sus propias historias.

Por su parte, Julio Valdez aborda desde la pintura cuestiones de índole identitaria y existencial. Experimentar en carne propia la migración de isla a “isla” (de

la República Dominicana a Manhattan) le confiere una especial aptitud para dialogar desde sus lienzos y papeles sobre su identidad: “Las circunstancias personales,

como alguien que ha vivido dentro de la isla y ahora vive fuera de ella, me permiten

continuar explorándome, construyéndome, con mayor agudeza de percepción. Los

horizontes se ensancharon. Así, el drama social de las migraciones y el exilio en el

28

Caribe también se filtran desde mi centro”. La serie donde el mar es protagonista

resulta intrigante y reflexiva. Lo es más su alusión, en el título de una de sus obras, a

“la maldita circunstancia (…) de agua por todas partes”, como lo expresó en La isla

en peso (1943) el magnífico escritor cubano Virgilio Piñera. Los símbolos y las metáforas a que recurre Valdez están definidos por la propia multiplicidad de lecturas,

“desde lo local (interno) hasta lo universal (externo), y así el mar/agua es lo que nos

une (internamente) y nos separa (mentalmente, a nivel de temperamento y emocionalmente) de los otros, de lo «de afuera»”. En cuanto al concepto de inmersión, ha

cobrado enorme importancia en la llamada realidad virtual debido a que el paradigma visual de ésta implica que el observador está dentro del mundo que observa.

Y así, los personajes (él mismo, su hermano, su conocido) están inmersos en el mar

y, a la vez, rodeados por él. El mar es aquí más amplio (como si fuera posible), es

agua. Fue también Piñera quien habló del plátano (“musa paradisíaca”) desde la isla.

Valdez lo aprovecha a manera de empapelado para dejar la impronta del retrato.

Así, el rostro es tan permanente como la referencia a este fruto tan común y representativo de la cultura dominicana.

Pintor y dibujante por vocación y por voluntad, Gerard Ellis establece una

interesante dicotomía entre el ejercicio de la pintura y la crítica social. Su obra

pictórica resulta sumamente expresiva y vigorosa para quienes participan de

manera directa o indirecta en los múltiples estratos de los contextos a que se refiere este artista. La violencia, la corrupción, la abulia propia de nuestros tiempos

y todo aquello que nos remite a la estupidez humana son temas centrales de su

cuidadísimo trabajo pictórico. Hay una estudiada conexión e interdependencia

entre lo que es su trabajo y lo que constituyen sus experiencias de vida, lo cual

se traduce en cierta politización subyacente de la experiencia vital. Su obra reactualiza cuestiones vinculadas al modo en que una mirada articulada en torno

a la realidad puede, a la vez, configurar ámbitos de reflexión en relación con la

experiencia de vida de cada individuo... y encubrir la más absoluta rebeldía. Son

piezas que nos conducen a esos deliciosos territorios del sarcasmo y la ironía

que sabe generar el autor. En buena compañía (2007) y Tierra maravillosa de

invierno (2008) son obras características de ese juego de palabras y de imágenes

en que no todo está dicho pero sí sugerido. Por otra parte, Mar bravo (2008) es

un testimonio del acto de crear, del proceso creativo en que se embarca Ellis.

Autorreferencial y en cierta medida autobiográfica, nos presenta el acto creador

y destructor del pintor sobre una hoja de papel, al tiempo que su esqueleto se

recubre de peces. En este espacio en blanco, relacionado con las hojas de las

libretas infantiles, hay un peso emocional menos sarcástico y más analítico de

las particularidades de su quehacer.

Una imagen extraña, dispuesta en un recuadro en un diario de circulación

nacional, fue motivo de preocupación general: “Santo Domingo Este. Una “yipeta” [camioneta] marca BMW, color negro, sin nadie a bordo, fue lanzada al

29

fondo del Mar Caribe no se sabe con qué propósito. La yipeta fue descubierta

bajo las aguas por un morador del área, que dio la voz de alarma”. Este texto

intrigante y extraño dio impulso a toda una serie de obras, cuerpos de trabajo

y centenares de horas de cavilaciones de Limber Vilorio. Aquel hecho absurdo y

tentador se convirtió en una secuencia lógica de todas sus líneas discursivas anteriores. A través de su mirada, la ciudad y sus habitantes, así como sus elementos constitutivos (tangibles o no), habían adoptado una dimensión emocional

que los refería a espacios artificiales, caóticos, catastróficos, apocalípticos… del

mismo modo en que Santo Domingo se transformaba ante sus ojos. Esa especie

de obsesión urbana llevó a Vilorio a rescatar los espacios prohibidos e innombrables de la urbe, a materializar la condena y el pesar de transitarla. Bajo su

mirada aparecen el mito, las señales, la marginalización, la violencia y las vidas

privadas que transitan por lugares públicos. Ya alguna vez exterioricé que Limber se enfrenta, mediante este conjunto de obras, a una sociedad que siente una

absoluta fascinación por el automóvil como símbolo de estatus y generador de

pasiones. En opinión del autor, el poder de la imagen, en obras como Ahogado

en su gasolina (2004), Vértigo (2004) y A la deriva (2006), radica “en su destrucción [la del carro]”. La desaparición del automóvil (así… genéricamente) es,

según sus propias palabras, “la liberación, el triunfo del yo frente al súper ego

colectivo”.

Finalmente, la obra de Radhamés Mejía se vincula a la República Dominicana, su patria, a partir de variados recursos simbólicos, que van desde las

pictografías, los petroglifos y el sistema geométrico de los aborígenes tainos

hasta aquellos asociados a la vida cotidiana actual del dominicano. De manera espontánea, el autor refiere a su ser isleño desde la memoria colectiva, la

música, la danza y los hábitos que conforman una identidad siempre en

construcción. En Cabezas llenas de plátanos (2008) divide la obra en tres

planos fundamentales, cuya base es ese recurso nemotécnico a lo taino y que

asciende a los rostros de perfil coronados por plátanos. La pieza está rematada, en su extremo superior, por unos zapatos con resortes que aluden

al trasiego, al traslado y al nomadismo del ser dominicano. Las boquitas o la

pomme (2008) y Posesión ritual (2008) procuran un vínculo más visceral y

afectivo con lo afrocaribeño también desde la perspectiva de lo simbólico,

geométrico y fragmentado de la condición insular. Santiago Villa Chiappe

había considerado que Antonio Benítez Rojo “concibe al Caribe como un

nexo y al mismo tiempo como una diseminación. Nexo, porque es un punto

de unión entre diferentes mundos, un encuentro de historias que crean una

comunidad imaginada, un «universo» cultural y una geografía. Diseminación,

porque el Caribe es un flujo de significantes”. Y es precisamente a estos nexos y

significantes y a ese encuentro de historias que se refiere Mejía cuando confronta al color con la geometría y al símbolo con su esencia.

30

Reeducando a Mónica II (Reeducating Monica II)

• 2008

MÓNICA FERRERAS

Adentro

Polibio Díaz es un fotógrafo que en su trayectoria ha evaluado desde múltiples pers-

pectivas las contradicciones y relaciones de las categorías de adentro y afuera. Al

plantear la profundidad del acto consciente del fotógrafo en la revelación de estas

polaridades, ya había expresado que la producción de imágenes en su serie Interiores (2001-2004) es consciente de sí misma, de las herramientas que la construyen,

del lenguaje que es posible articular mediante ella y de los mecanismos perceptivos

que permiten que un espectador la reciba y pueda interpretar relacionándola con

su propia experiencia (la del retratado y la de quien retrata). Díaz brinda una sagaz

impresión de la vida en la contemporaneidad dominicana a través de una perspectiva desde “adentro”. Incorpora para ello el mobiliario y la parafernalia hogareña del

dominicano, creando un colorido exuberante aunque paradójicamente sereno, con

31

Después de la siesta (After the Nap)

• 2001-2004

POLIBIO DÍAZ

interesantes observaciones sobre la vida diaria y la memoria de quien habita esos

espacios. Sus interiores ilustran una actitud de la sociedad contemporánea a partir

del núcleo del hábitat. Consciente del influjo de la cultura consumista y del creciente materialismo, intenta registrar en su fotografía las escenas a que dan lugar estas situaciones. La publicidad, los medios masivos —representados por televisores y

radios—, las imágenes icónicas y trascendentes de la religiosidad popular y las flores

de plástico emprenden su camino a la sacralidad en estos momentos congelados.

Inés Tolentino se renueva constantemente. Sus pinturas, dibujos y collages son

una referencia reflexiva a su propia biografía… y con la de ella, a la de la mujer

en general. Su cuerpo de trabajo más reciente nos conduce a entender la memoria cuerpo como un lugar de confluencia y paradójico conflicto. La memoria,

su memoria corporizada a partir del “noble” acto de bordado, redimensiona las

categorías de lo femenino y de la representación, desde sus propios imaginarios

hasta los que considera colectivos, metáforas de lugar y rituales, creencias y labores. Tejiendo mi historia (2008) nos aporta desde el principio esa idea del acto

de bordado como un gesto de íntimas referencias, ya sea a lo doméstico como

a la obsesiva pasión por adornar y embellecer. Ahora bien: ¿cómo ornamentan

estas puntadas? Lo hacen a partir de símbolos simples y llanos, que nos remiten

a la guerra, al sexo, a los diálogos inocuos, a los dibujos animados y hasta al

sagrado corazón de Jesús. Estas referencias, que en apariencia se muestran ingenuas, van articulando un discurso sobre las estructuras y los esquemas que

“organizan” la vida de la mujer en nuestras sociedades. Asimismo, Hilos de vida

(2008) construye una historia de violencia y muerte que, aun cuando la autora

se la apropia desde el título, bien podría constituir el relato acerca de los miles

de mujeres agredidas y sacrificadas por la violencia doméstica y los conflictos

armados en todo el mundo.

32

Mónica Ferreras se proclama junguiana, y los conceptos de Carl Jung aparecen

progresivamente en su obra. Sus pinturas, fundamentalmente autobiográficas, reflejan su proceso de individuación (la manera, definida por Jung, en que cada uno de

nosotros viene a ser lo que intrínseca y potencialmente es), a través del cual nos propone un laberinto que simboliza el viaje hacia el ser. Desde estas piezas plenas de

formas orgánicas (amebas, células, cadenas de ADN) y un tanto laberínticas, Ferreras nos expone a la complejidad del mundo psíquico (los vericuetos del consciente y

el subconsciente del individuo), trasladado al lienzo de modo instintivo. Su forma de

introducirlo en este cuerpo de trabajo parte de una experiencia de vida, una metáfora de su vida como individuo y de su vida como ser social. Reeducando a Mónica

(2008) es una serie de pinturas que reflejan esta línea discursiva desde una densidad

semántica sustentada en teorías analíticas acerca del ser humano y su personalidad.

Su video C.A.E (cuerpo, alma y espíritu (2005) nos muestra, en primero y único

plano, una escena de tres mujeres en constante movimiento que actúan ciertos ritos

y funciones que, se entiende, les pertenecen dentro del marco (literal) de un entorno

doméstico. Para ello, la artista parte de la trinidad establecida por el cuerpo, el alma

y el espíritu como base composicional. Esta visión, asociada a la deconstrucción de

las representaciones sociales de la mujer en la sociedad, interpela al espectador ante

las expectativas que tiene sobre el accionar en pantalla.

Fuera del Caribe se han realizado importantes exposiciones que incluyen las

propuestas visuales y de sentido de los dominicanos —unas con mayor enjundia

que otras, unas con menos prejuicios que otras—. Sin embargo, si algo trasciende

de estos esfuerzos por organizar una visualidad o potenciar una visión es, precisamente, el hecho de que se establecen interacciones entre artistas, instituciones y

curadores, y de cierta manera los discursos se contaminan para permitir lecturas que

surgen de esos vínculos sugeridos. A partir de esto se pueden desplegar entre ellos

movimientos de apertura y diálogo que posibiliten una nueva dinámica, aquella que

ha sido y será determinada y pautada por los propios productores de sentido.

Sara Hermann

ASESORA DE ARTES VISUALES

Centro Cultural Eduardo León Jimenes

Santiago de los Caballeros, República Dominicana

1-“El olor sabe arrancar las máscaras de la civilización,

sabe que el hombre y la mujer se encontrarán sin falta en el platanal.

¡Musa paradisíaca, ampara a los amantes!

No hay que ganar el cielo para gozarlo, dos cuerpos en

el platanal valen tanto como la primera pareja, la odiosa

pareja que sirvió para marcar la separación.

¡Musa paradisíaca, ampara a los amantes!”

(Virgilio Piñera. La isla en peso. 1943).

33

Good Companion (En buena compañía)

GERARD ELLIS

34

• 2007

Artists’ Biographies

Biografías de los artistas

35

Pasiones interiores (Inner Passions)

• 2 0 0 1 -2 0 0 4

POLIBIO DÍAZ

Polibio Díaz

{ polidiaz @ codetel . net. do }

Polibio Díaz Barahona was born in 1952, in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.

He studied photojournalism (1972) at the Texas A&M University, in College

Station, Texas, graduating from that university as a civil engineer (1973).

He has exhibited individually in Santo Domingo at the Museum of Modern

Art (“Cátedras Santa María de la Encarnación, 6 A.M.–6 P.M.,” 1982), at the

Dominican-German Cultural Center (2007), and at the Spanish Cultural Center (“Polibio Díaz, Photographs, Videoperformances and Installations,” 2008), as

well as at the Galerie André Arsenec in Martinique (“Interiors and Videoperformances,” 2008). His show “Una isla, un paisaje” was exhibited at the Casa de

América in Madrid (2002), at the Istituto Italo-Latinoamericano (IILA) in Rome

(2001), at the Centro Cultural del Matadero in Huesca, Spain (2000), and at the

Museum of Modern Art in Santo Domingo (1998).

He has participated in group exhibitions at the Fifty-First Venice Biennale

(Latin American Pavillion, IILA, Palazzo Franchetti, 2005) and at the Ninth Havana Biennial, in Cuba (2006), and in exhibits at the Brooklyn Museum, in New

York (“Infinite Island, Contemporary Caribbean Art,” 2007) and at the OAS Art

Museum of the Americas in Washington, D.C. (“¡Merengue! Visual Rhythms,”

2007). Additionally, he will participate in an exhibition at the Grande Halle de la

Villette in Paris (“Des îles et leurs mondes,” 2009).

Mr. Díaz lives in Santo Domingo.

36

Sin titulo (Untitled)

• 2001-2004

POLIBIO DÍAZ

Polibio Díaz Barahona nació en 1952 en Santo Domingo, República Dominicana.

Estudió Fotoperiodismo (1972) en la Universidad Internacional de Texas

A&M, en College Station, Texas, Estados Unidos, en la cual se graduó como

Ingeniero Civil (1973).

Ha expuesto individualmente en el Museo de Arte Moderno (“Cátedras Santa

María de la Encarnación, 6 am. – 6 pm.”, 1982), en el Centro Cultural DomínicoAlemán (2007) y en el Centro Cultural de España (“Polibio Díaz. Fotografías, videoperformances e instalaciones”, 2008),

todos de Santo Domingo; en la Galería

Andrés Arsenec, de Martinica (“Interiores y videoperformances”, 2008); y su

muestra “Una isla, un paisaje” fue exhibida en la Casa de América, de Madrid

(2002), en el Istituto Italo-Latinoamericano (IILA), de Roma (2001), en el Centro Cultural del Matadero, de Huesca,

España (2000), y en el Museo de Arte

Moderno en Santo Domingo (1998).

Colectivamente, ha participado en la 51ª Bienal de Venecia (Pabellón de

América Latina, IILA, Palazzo Franchetti, 2005); en la 9ª Bienal de La Habana,

Cuba (2006); en el Brooklyn Museum de Nueva York (“Infinite Island, Contemporary Caribbean Art”, 2007); en el Museo de Arte de las Américas de la OEA,

en Washington, D. C. (“¡Merengue! Visual Rhythms”, 2007), y participará en el

Grande Halle de la Villete, de París, Francia (“Des îles et leurs mondes”, 2009).

Vive en Santo Domingo.

37

Posesión ritual (Ritual Possession)

RADHAMÉS MEJÍA

38

• 2008

Radhamés Mejía

{ mejia @ free . fr }

Leonidas Radhamés Mejía was born on February 24, 1960, in Santo Domingo, Do-

minican Republic.

He received his degree from the National School of Fine Arts in Santo

Domingo (1979), where he later taught as Professor of Drawing. He subsequently studied printmaking and sculpture at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts, in

Paris-Cergy, France (1985).

He has exhibited individually at the Casa de los Jesuitas (“Objectivo,” 1981) and at the Museum of Modern Art

(1982), both in Santo Domingo; at the Galería Bernheim

in Panama (1992); at the gallery of the Orly Sud Airport in

Paris (“Limites archaïques,” 1996); and at the Museum of

the Americas in San Juan, Puerto Rico (2000).

He has participated in group exhibitions at the Eduardo León Jimenes Art Contest of the Centro León in Santiago de los Caballeros,

Dominican Republic (1981); at the Third Biennial of Ibero-American Art of the

Domecq Cultural Institute in Mexico City (1982); at the OAS Art Museum of the

Americas in Washington, D.C. (“Signs and Symbols of the Dominican Republic,”

1986); in the Salons de mai at the Grand Palais in Paris (1989–1993); and in the

Triennale des Amériques in Maubeuge, France (1993). He was also invited to

participate in the experimental workshop “Cuerpos pintados” in Chile and in the

design of the book by the same title (2004).

Mr. Mejía lives in Asnières (near Paris), France.

Leonidas Radhamés Mejía nació el 24 de febrero de 1960 en Santo Domingo,

República Dominicana.

Obtuvo su diploma en la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes de Santo Domingo (1979), en donde ofició luego como profesor de Dibujo. Posteriormente

estudió Grabado y Escultura en la École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de ParísCergy, Francia (1985).

39

Las boquitas o la pomme (The Hors d’Oeuvres or The Apple)

• 2008

RADHAMÉS MEJÍA

Ha expuesto individualmente en la Casa de los Jesuitas (“Objetivo”, 1981)

y en el Museo de Arte Moderno (1982), de Santo Domingo; en la Galería Bernheim de Panamá (1992); en la Galería del Aeropuerto de Orly Sud, París, Francia

(“Limites Archaiques”, 1996), y en el Museo de la Américas de San Juan, Puerto

Rico (2000).

Colectivamente, ha participado en el Concurso León Jimenes del Centro

León, en Santiago de los Caballeros (1981); en la III Bienal de Arte Ibero-Ame-

40

Cabezas llenas de plátanos (Heads Full of Plantains)

• 2008

RADHAMÉS MEJÍA

ricano del Instituto Cultural Domecq, en Ciudad de México (1982); en el Museo

de Arte de las Américas de la OEA, en Washington, D.C. (“Signs and Symbols of

the Dominican Republic”, 1986); en los Salons de mai, Grand Palais, de París,

Francia (1989-1993); en la Triennale des Amériques, en Maubeuge, Francia

(1993); y fue invitado a participar en el taller experimental “Cuerpos Pintados”,

en Chile, y en la edición del libro que lleva el mismo nombre (2004).

Vive en Asnière (cerca de París), Francia.

41

Inés Tolentino

{ [email protected]

}

Inés Tolentino was born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, on June 30, 1962.

She studied at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts, in Paris-Cergy (1981–1985);

she received both her B.A. (1983) and her M.A. (1984) in Plastic Arts and Art Sciences from the University of Paris I, Panthéon-Sorbonne. She also pursued specialized studies in aesthetics and ethno-anthropology (1986).

She has exhibited individually at the Château-Musée

Grimaldi in Cagnes-sur-Mer, France (“Inés Tolentino: Recent Works,” 1995); at the Galería Botello, in San Juan,

Puerto Rico (“Babel de día y de noche,” 1999); at the Museum of Modern Art, in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (“Imágenes de archivo,” 2002); at the Galerie d’Art

Viviana Grandi in Brussels, Belgium (“Memoria del Caribe,” 2003); and at the

Galerie JM’Arts in Paris (“Las hacendosas,” 2008).

She has participated in group exhibitions at the Sixth Havana Biennial in Cuba

(1997); at the OAS Art Museum of the Americas in Washington, D.C. (“Mastering

the Millennium: Art of the Americas,” 1999); in the traveling exhibition entitled

“200 Years of Pernod” (2005) shown at the Espace Paul Ricard in Paris and also

in Nantes, Lyon, Bordeaux, and Marseilles; and in an exhibition at the Musée de

l’Aquitaine in Bordeaux (“Art of the Caribbean Islands,” 2008).

Ms. Tolentino currently lives in Paris.

Inés Tolentino nació en Santo Domingo, República Dominicana, el 30 de junio de 1962.

Estudió en la École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de París-Cergy (1981-1985),

obtuvo su licenciatura en Artes Plásticas y Ciencias del Arte en la Universidad de

París I, Panteón Sorbona (1983), y posteriormente la maestría en Artes Plásticas y

Ciencias del Arte (1984). Realizó, además, estudios especializados en Estética y

Etno-Antropología (1986).

Ha expuesto individualmente en el Château-Musée Grimaldi de Cagnes-surMer, Francia (“Inés Tolentino, obras recientes”, 1995); en la Galería Botello de

42

Coseré mi corazón en el tuyo (I Will Sew My Heart to Yours)

• 2008

I N É S TO L E N T I N O

43

Hilos de vida (Threads of Life)

I N É S TO L E N T I N O

44

• 2008

Tejiendo mi historia (Weaving My Story)

• 2008

I N É S TO L E N T I N O

San Juan, Puerto Rico (“Babel de día y de noche”, 1999); en el Museo de Arte

Moderno de Santo Domingo, República Dominicana (“Imágenes de Archivo”,

2002); en la Galería Grandi de Bruselas, Bélgica (“Memoria del Caribe”, 2003),

y en la Galería JM’Arts de París, Francia (“Las Hacendosas”, 2008).

Colectivamente, ha participado en la VI Bienal de La Habana, Cuba (1997);

en el Museo de Arte de las Américas de la OEA, Washington, D.C. (“Mastering

the Millennium: Art of the Americas”, 1999); en el Espace Paul Ricard de París y

Marsella, Francia (“Los 200 años de Pernod”, 2005), y en el Museo de Aquitania

de Burdeos, Francia (“Arte del Caribe Insular”, 2008).