vichuquén

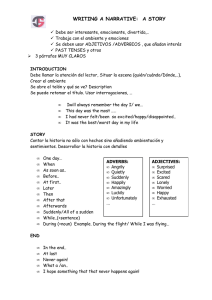

Anuncio