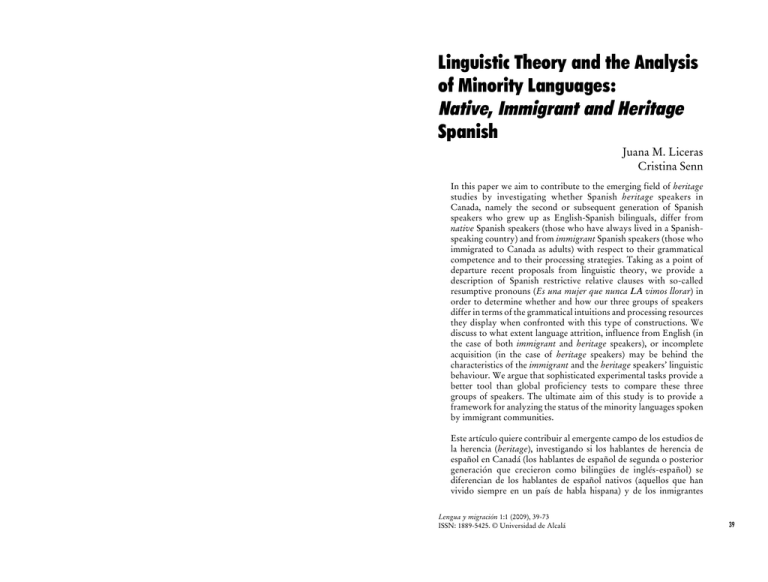

Linguistic Theory and the Analysis of Minority Languages

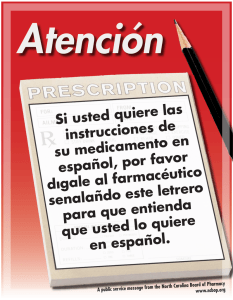

Anuncio