operation sofía - Confederación Sindical de Comisiones Obreras

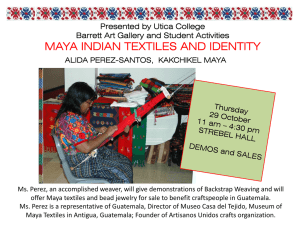

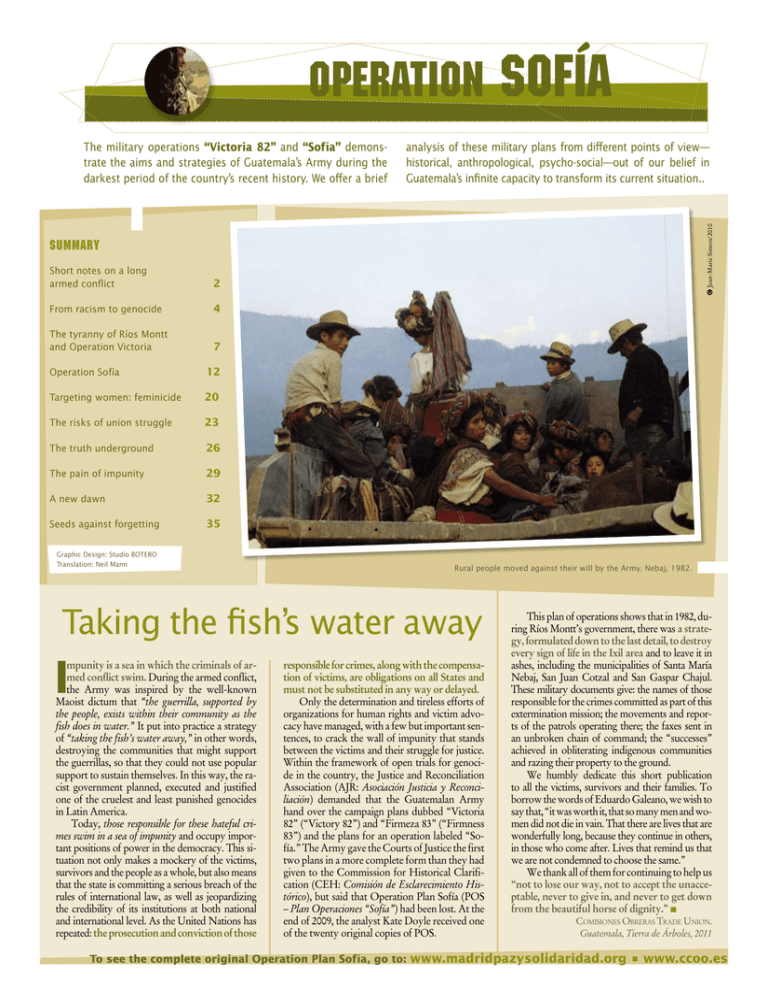

Anuncio