Ryan Anthony Spangler - People at Creighton University

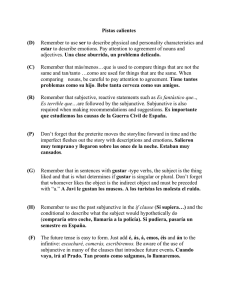

Anuncio

Ryan Anthony Spangler University of Kentucky 468 Plainview Road Lexington, KY 40517 phone: (859) 335-0233 fax: (859) 323-9077 [email protected] Approaching the Modern in Martí: The Aura of Authenticity in Spanish-American Modernismo 1 Approaching the Modern in Martí: The Aura of Authenticity in Spanish-American Modernismo Abstract: This paper deals with the interpretation and manifestation of modernity within the writings of José Martí. It analyzes Martí’s prose and poetry and delineates the martian expression of modernity as an authenticated and sincere poetry. However, due to the incapacities of language, it exposes Martí’s inability to realize such spontaneous and unlabored poetry. What compensates for his failure is the idealistic drive towards a heroic and genuine poetics that reveals his internal moral push for authenticity. True spontaneity is an expression of pain and sorrow that characterizes the overarching pursuit for sincerity. Martí’s expression of modernity revealed in his poetry ultimately realizes the true modern spirit of originality that the modernistas who follow him will in turn attempt to achieve. Key words: Modernismo, José Martí, modernity, poetry, authenticity, Romanticism, Positivism, Ismaelillo, Versos libres 2 Approaching the Modern in Martí: The Aura of Authenticity in Spanish-American Modernismo Pon de lado las huecas rimas de uso, ensartadas de persas y matizados con flores de artificio, que suelen ser más juego de la mano y divertimiento del ocioso ingenio que llamarada del alma y hazaña digna de los magnates de la mente. Junta en haz alto, y echa al fuego, pesares de contagio, tibiedades latinas, rimas reflejas, dudas ajenas, males de libros, fe prescrita, y caliéntate a la llama saludable del frío de estos tiempos dolorosos en que, despierta ya en la a mente la criatura, adormecida, están todos los hombres de pie sobre la tierra, apretados los labios, desnudo el pecho bravo y vuelto al puño al cielo, demandando a la vida su secreto. -José Martí, «Prólogo al Poema del Niágara» When José Martí (1853-1895), one of the progenitors of Modernismo, first proposed in the «Prólogo al Poema del Niágara» his rejection of “empty used rhymes […] mixed with artificial flowers,” he addressed the trend among Latin American and Spanish Romantic writers of his day to abandon poetic sincerity in order to imitate their European counterparts. “La modernidad,” according Paz, “nunca es ella misma: siempre es otra” (Los hijos del limo 408). That is, modernity signifies a critique, rupture, or break from something else, a push for immediacy: a newness. Martí, like the Romantics and Symbolists before him, broke from the trend of imitation in order to define the terms of his own modern poetry—a voice of sincerity, ethics, and a heroic, prophetic vision. Martí denied emphatically his relationship to his Spanish American literary contemporaries that specialized in the imitation of their authentic European counterparts. Instead, he felt that “las ideas no hacen familia en la mente, como antes, ni casa, ni larga vida. Nacen a caballo, montadas en relámpago, con alas (64 italics mine). Poetry, for Martí, should be a written manifestation of what the poet feels and perceives instead of breeding in the mind as done by the Spanish Romantic writers before him. Martí’s ambivalent language expressed a poetics that exemplified his idealistic politics and morals that had come to distinguish him from his contemporaries. However, even though Martí created a distinct poetic voice, his conscious attentiveness to his poetic surroundings addressed the major concern of modernity that confronted many other writers in Latin America. Although this essay will not focus on any of the other Spanish American Symbolists, I feel Martí’s “Prólogo” to be useful in setting the stage in addressing the question of modernity in the Spanish American fin de siècle. The primary participants in this movement, ie. José Martí, Rubén Darío, Leopoldo Lugones, Delmira Agustini, etc., each attend to this issue of modernity through their distinct expressions of rupture. My intent is to discuss the notion of modernity and afterwards pinpoint the mode of rupture in Martí as a groundwork for the other authors of Modernismo. Using an assortment of prose and poetry, I aim to outline the unique position of Martí and reveal his authentic perception and manifestation of modernity. 3 Literary modernity is ultimately the modern confronting the modern. What I mean is that modern literature deals firsthand with the dilemma of technological and scientific advancement by approaching the spiritual emptiness often left by its presence. As scientific modernity continued to distance itself from literary modernity, writers began to analyze simultaneously both the question of technology and the exploration of liberated writing, demonstrated in the fragmentary style of Schlegel and Novalis. Authors began to use poetry to question the thematic boundaries of literature, by exploring the realm of politics, ethics, intimate relations, and experimental religious ideas. This thematic break ultimately lead to a rupture in the structure of poetic form, thus paving the way for German and English Romanticism, French Symbolism, and Spanish American Modernismo. The appearance of Auguste Comte’s Positivism, and later Herbert Spencer’s Social Darwinism in Latin America, often considered the precursors to Modernismo, emerged among the political circles from Mexico to Argentina. Benito Juárez’s implementation of it that later continued during the Porfiriato (1876-80, 1884-1910 created the cultural context for one of the foundational modernistas, José Martí. Although a native of Cuba, Martí (1853-1895) was exiled at the age of eighteen from the island and lived in Spain until 1874. Unable to return to Cuba, but with a desire to return to America, Martí joined his family in Mexico. His three-year stay in Mexico occurred during the transition from Lerdo de Tejada to Díaz; a period that coincided with a burgeoining positivistic politics. Martí witnessed the institutionalization of positivism through the government’s persecution of the church in Mexico, the secularization of the state, and the proliferation of state-funded education. The “scientific” solution to politics that Martí observed, greatly affected his internal perception of government as he searched for solutions to Cuba’s situation under Spanish dominance. He realized that such an approach to the problem at hand left a spiritual absence that failed to explain artistic creation. Although Martí’s rejection of positivism and Social Darwinism has often been considered the source of his modernista poetry, it would be misleading to view this political tumult as the sole factor that led to his poetic search for the heroic, sincere, and spontaneous to which he alludes in his “Prólogo.” While his confrontation with positivism and United States imperialism became most overtly manifest in his prose, very little of his poetry actually addressed the surge of positivism within Latin America, at least explicitly. Instead, Martí sought to create an impulsive, spontaneous voice that demonstrated his search for a genuine, authentic poetry, unlike many Spanish American and Spanish Romantics who continued to imitate their French, German, and English contemporaries. And as Paz notes, it is Martí’s incorruptible nature that led to the sincerity of his poetry and the personal sacrifice of his life for his country (Los hijos del limo 501). In order to understand this, however, we need to return to the “Prólogo.” Martí first wrote the “Prólogo al «Poema del Niágara» de Juan A. Pérez Bonalde” in 1882, the same year Ismaelillo, his first collection of poetry, appeared. This essay, which characterizes Martí’s perception of a more authentic poetry, is divided between his description and meditation of modern times and poetry, and the actual prologue to Pérez Bonalde’s poem. His essay pinpoints the problems of imitation, labored verse, and the veiling of human burdens found in the verses of his contemporaries in Spain and Latin America. He writes: 4 ¡Este que traigo de la mano no es zurcidor de rimas, ni repetidor de viejos maestros —que lo son porque a nadie repitieron—, ni decidor de amores, como aquellos que trocaron en mágicas cítaras el seno tenebroso de las traidoras góndolas de Italia, ni gemidor de oficio, como tantos que fuerzan a los hombres honrados a esconder sus pesares como culpas, y sus sagrados lamentos como pueriles futilezas! Este que viene conmigo es grande, aunque no lo sea de España [...]. (59) Martí notes that literature in Spain and Spanish America had come to be characterized as mended rhymes and the repetition of old masters, stories of love and words that conceal the sacred laments of the soul and convert them into childish trivialities. Each of these defects counters what Martí considers to be authentic poetry, leaving only “esa mutilación de nuestros hijos, ese trueque del plectro del poeta por el bisturí del disector! Así quedan los versos pulidos” (74). Instead of springing from within like a newborn child, the inspired verses are manipulated and contorted into something that barely resembles what they first were. “Las convenciones creadas,” he affirms, “deforman la existencia verdadera, y la verdadera vida viene a ser como corriente silenciosa que se desliza invisible bajo la vida aparente” (68). The borrowed poetics used by an author completely silence the actual message and “deform the true existence” of the message. As he states, “ahora el poeta ha mudado de labor, y anda ahogando águilas” (60). This construction and laboring of verses, according to Martí, drowns the natural voice; it demonstrates a lack of newness or spontaneity. It may exhibit what is in the mind, but covers the original visionary inspiration of the poet. The genuineness of a verse depends not only on how it first came from the poet, but whether or not the original message remained untainted. The preservation of the original message concerns Martí to the point of his labeling any other type of verse as “pesares de contagio, tibiedades latinas, rimas reflejas, dudas ajenas, males de libros, fe prescrita” (78). His second complaint, the “repetidor de viejos maestros,” identifies the manner in which authentic poetry becomes silenced; through the imitation of previous writers. Most poetry in Spain during the nineteenth century imitated the earlier English and German Romantics. In Martí’s view, Spanish America’s writers merely imitated their Spanish counterparts, thus making poetry in the Americas a repetition of imitated verse. Poetry wreaked of artificiality and lacked the novelty that Martí sought. Next, he condemns sentimental verse, especially words that duplicate and thus betray the originality and sensitivity of petrarchian structure and themes. This style, evident among such writers as Espronceda and Bécquer (though he never names them specifically), expresses more a sentimentality—a longing for an unknown and artificial love—than actual love. “El amor,” Martí explains, “rebosa y se esparce [...], entona cantos fugitivos, mas no produce —por sentimiento culminante y vehemente cuya tensión fatiga y abruma — obras de reposado aliento, y laboreo penoso” (63). The sentimental poetry that he condemns does not express a true aspect of love because its message has been tempered into a new form. It is merely stagnant air, like the words that express it. The higher love spoken of by Martí cannot be contained nor directed to an individual. It bubbles over and scatters itself to effect a change in everyone that feels its presence. Poetry should resemble that love. 5 Martí also condemns the obscuring of “pesares como culpas” and transforming sacred laments into childish trivialities. Santí notes that Martí considered Ismaelillo to be his first true book for “la manera en que asumió su condición de poeta,” –his recognition of his dolores graves – “y en la manera en que esa experiencia se transparentó en los poemas de Ismaelillo” (35). Probably the most characteristic and problematic of Martí’s critique of his contemporaries, and commensurate defense of his own poetics, is this notion of sincerity, which echoes throughout all of his works. In every case of his poetry, he attempts to reveal the burdens, misfortunes, and tragedies of his own life without any sort of reproachful accusation directed toward them. The revelation of adversity, for Martí, corresponds with the sacred, raising the poet to the status of Job, or even Christ. Like so many of the Judeo-Christian archetypes to which he subtly refers, the acceptance of such pain and reality only elevates the individual to a level of clearer comprehension. He/She gains the ability to overlook the trivialities of life and focus on the enlightenment of others. And while Martí may not be capable of clearly expressing the anguish that he often experiences, his attempt to allow it to spring forth unadulterated without manipulation exemplifies his desire for the conservation of the pure images, feelings, and ideas first received by the poet. The final words of the “Prólogo,” already cited in the epilogue of this essay, reaffirm Martí’s desire to replace the empty, overworked rhymes with a sincere voice that clearly expresses the poet’s visionary experience. Mankind “[demanda] a la vida su secreto” (78), and it is the poet’s responsibility to reveal that. This secret is only contained in the spontaneous and sincere voice of an unlabored poetry, not the verse Martí so vehemently rejects. And rather than strive to create, mend, or imitate anything, he advises the poet to do something else: “caliéntate a la llama saludable del frío de estos tiempos dolorosos.” That is, allow the verse to be born out of your own suffering. Such is Martí’s proposed poetics. The three books of poetry that Martí writes while living in New York, Ismaelillo (1882), Versos libres1 (1880’s, but published posthumously in 1913), and Versos sencillos (1891), each address the problem of modernity as they propose a poetry of heroics—poetry that conveys the visionary experience of the author—that embodies the modernista spirit of novelty and unrepeatable time. My intention is to address the opening and introductory poems to two of these works, Ismaelillo and Versos libres and highlight how Martí attempts to distinguish himself from the “huecas rimas de uso” that he so overtly rejects. However, this reading will also reveal Martí’s ultimate inability to carry out his project to liberate poetic language. Ultimately, I will demonstrate the uniqueness of Marti’s modernity as he creates a voice that distinguishes him from both his precursors and his modernista contemporaries. Martí’s proposed poetics is rather problematic in that he contradicts himself as he attempts to define his notion of poetry while writing within the guidelines that he has established for himself. Ranging from the simplicity of Versos sencillos to the difficult vocabulary of Versos libres, his poetry confounds both critics and readers alike who attempt to decipher the message encoded in his works. Although his poetic style and approach to modernity may seem confusing, each work projects the similar themes of originality, spontaneity, and most importantly, sincerity. In this prologue to Ismaelillo he writes: 6 Hijo: Espantado de todo, me refugio en ti. Tengo fe en el mejoramiento humano, en la vida futura, en la utilidad de la virtud, y en ti. Si alguien te dice que estas páginas se parecen a otras páginas, diles que te amo demasiado para profanarte así. Tal como aquí te pinto, tal te han visto mis ojos. Con esos arreos de gala te me has aparecido. Cuando he cesado de verte en una forma, he cesado de pintarte. Esos riachuelos han pasado por mi corazón. ¡Lleguen al tuyo! (57) Martí defends his poetry and, in effect, certifies his own authenticity as an author. The hijo to whom he directs it, can be interpreted in a number of manners: his actual son, José Francisco, who had recently departed New York with his mother, Carmen Zayas Bazán, and returned to Cuba. Martí’s explanation duly expresses his desire to reveal to his son the manner in which he sees him, as well as assert his originality. Implicitly, however, Martí refers to the reader, who like a child, will be viewing his book for the first time. In this sense, he asks that we look at it with newness, in the fresh way a child perceives life. Thus, Martí, or his implied author, addresses each of us as his son and hopes to persuade us of his authenticity as a poet. And although his work addresses a child, it is in no way a childish triviality. “Ismaelillo,” states Enrico Santí, “no pertenece al género de la literatura infantil; es decir, no es tanto un libro escrito para niños como un libro sobre un niño” (23). Martí uses the image of the child to call upon a fresh, uncluttered vision and to then confirm the reality of his sorrows expressed through his poetry. In so doing, Martí reaffirms his belief in the poetic standards he described in the “Prólogo” by addressing each point that he considered then of greatest importance in the production of poetry. He begins by stating that he is “espantado de todo,” thus asserting his own frustrations and fears in life. He does not in anyway attempt to “esconder sus pesares como culpas” (“Prólogo” 59), but rather, insists upon revealing his personal troubles. Such a manifestation promotes Martí’s attempt to unveil the sacred laments that he considers his work to be. And by so doing, he asserts that his work is faithful to the experiences and visions he attempts to relate. The second paragraph in the Ismaelillo prologue expresses the areas of Martí’s faith: the betterment of humanity, the future life, the utility of virtue, and a multipledirected you. These areas confirm Martí’s teleological drive for change—an objective to transform the current reality into the vision of the child—and work collectively to produce the type of poetry that mirrors what the poet has beheld. The first expresses a yearning to overcome the burdens that inflict him. “Future life” refers of course to the reality of the present, and the poet’s failure to realize linguistically his vision. By looking towards the future, Martí recognizes his current incapacity to produce the type of verse that he promotes in his prologue. Secondly, he is also referring to his belief in a life after the one he now knows. In the “Prólogo” he states “La imperfección de la lengua humana para expresar cabalmente los juicios, afectos y designios del hombre es una prueba perfecta y absoluta de la necesidad de una existencia venidera” (75). Martí articulates a need for a coming existence to overcome the poetic struggles that our insufficient language causes. He deems that it is only through the realization of this life to come that language will be perfected, where signifier and signified will be one, and the “secreto” of 7 the poet will be revealed. His intended poetics, impossible in this life with the linguistic tools he currently possesses, can only be achieved in a future life, whether that life be contained in the manifestation of the child, or in a life we have yet to know. Martí then expresses his faith in the utility of virtue, a statement that conveys his personal standard of ethical writing as well as his desire for change in the world around. While there are traces of a political agenda in this statement, I believe his intention was directed more to the poetic dilemma at hand. By articulating his moral idealistic stance through the projection of virtue, he raises the bar in the production of poetry, specifically for himself and for those who read his work. Finally, the tú to whom he is referring once again goes back the idea of the hijo and what that suggests. Martí, along with the dedication of his book to his son, his Ismaelillo also refers to the poets and readers of his work. His goal advocates a change not only in the role of the poet, but also of the reader. We must change how we read and look at poetry and reevaluate the emphasis we often place on aesthetics at the cost of sacrificing the ethical value of the poetry. The promotion, acceptance, and most importantly, the realization of his poetic ideal rests upon his readers. By invoking a nameless tú, he is calling upon everyone to cast aside the empty verse of his day and search for a more authentic voice. For this purpose, the next paragraph of the prologue for Ismaelillo exemplifies Martí’s resolution to assert his status as an honorable, sincere writer. His pen writes only according to what he sees, and does not get entangled in the problem stylistics and aesthetics. His verse, like the streams that pass through his heart, are in constant flux. They do not stagnate in his mind as he ponders upon the precise words to select; instead, they constantly flow out from him, similar to the verses “montadas en relámpago, con alas” (“Prólogo” 64) that he speaks of in the “Prólogo.” Up to now, I have relied solely upon two prologues to discuss Martí’s poetic ideals. As will be seen later, as I analyze the prologues from another of his two works of poetry, he never retracts from his proposed poetics, but rather, continually promotes his idealized notion of a sincere, untampered art that does not bow to the gods of versification or rhyme. Yet, as we read through Martí’s actual poetic work, we begin to recognize the incapability of Martí to realize the art that he so resolutely endorses. The opening of the first poem of Ismaelillo, “Príncipe enano” illustrates the point perfectly. Para un príncipe enano Se hace esta fiesta. Tiene guedejas rubias, Blandas guedejas; Por sobre el hombro blanco Luengas le cuelgan. Sus dos ojos parecen Estrellas negras: Vuelan, brillan, palpitan, Relampaguean! Él para mí es corona, Almohada, espuela. 8 The title implies a political syncretism with childhood. The prince, a figure of power, becomes molded to the dwarf, a reference to the child. Thus, the title projects the clear image of a child at play, as if taking on an adult responsibility. Martí uses the child as a form of mediation to give the reader the perspective of a child and see the world with innocent eyes. Both father and reader desire to participate in the experience through the game’s creation. Martí opens the poem with a dedication to the dwarf prince. Yet, the words used by the author result in a party, and not only a poem. We begin to see the simplicity of the child’s life and recognize the game not as an escape but a reality. As adults, we use games in order to divert the pains and troubles, work and responsibilities, that burden us. But for a child, life is a constant game, a flux of words, actions, vision, and imaginations. The poet allows the adult to participate in the child’s game and sees it as reality instead of as distraction. Secondly, the poet uses the image of the child in order to break from the semantic structure of narrative poetry. Martí accentuates the necessary drive towards lyrical poetry in order to give greater freedom to the poet and unbind him/her. This authorial stress is a critique of the linearity and the semantic axle of narrative poetry, as it rejects linear time in favor of a broader perception of reality that places the poem in a sequence of moments and spaces. Martí uses this technique as a means of assaulting the question of form. However, such a conscious effort on the part of Martí contradicts his overall project of liberated verse. For by overtly fighting against the linearity of narrative verse, he reveals the construction used to create his verse and denies the spontaneity he promotes. He also remains tied to traditional Spanish heptasyllablic meter. It can be argued, however, that such a meter is traditional not only in Spanish verse, but also in spoken dialogue. Many of the common idiomatic expressions in Spanish follow either a heptasyllabic or octosyllabic structure. Nevertheless, Martí’s meter is laced with archaic words (guedejas, luengas) used to carry both meter and rhyme scheme. He also uses assonant rhyme throughout the poem, an indication of his premeditation or re-articulation of the verse form. Thus, while Martí’s prologue boasts spontaneity, his verse works otherwise. Perhaps what Martí does divulge in this poem is a desire to attain the poetry he discusses in the book’s prologue. He admires the innocent child’s position and attempts to express through an incapable language—a language unable to completely convey the vision of the poet or the child—the perspective that he/she has in a game. The child’s simplistic lifestyle is thus similar to the visionary perspective Martí endeavors to communicate throughout his poetry, all the while recognizing his inability to do so. The overarching goal of sincere, spontaneous, heroic poetry Martí endorses becomes realized only in the very act of the game of childhood because though it is reality for the child, it is merely a refuge for the adult. Martí’s second collection of poetry, Versos libres, comes closer to his proposed heroic poetry as he expresses the anguish of displacement and abandonment felt during his time in New York. With regards to this book of poetry, Martí states, “Mis encrespados Versos Libres, mis endecasílabos hirsutos, nacidos de grandes miedos, o de grandes esperanzas, o de indómito amor de libertad, o de amor doloroso a la hermosura, como riachuelo de oro natural, que va entre arena y aguas turbias y raíces, o como hierro caldeado, que silba y chispea, o como surtidores candentes” (Schulman 37-8). Unlike Ismaelillo, which is born from the vision Martí has of his son, and poetry in general, Versos libres expresses the pain, sorrow, hope, and love that he sees and feels. It 9 distances itself from the futuristic visionary poetry of Ismaelillo and communicates the angst Martí feels at the time his wife and child left him for good in New York. However, like his earlier book, Versos libres attempts to convey the inner sentiments of the poet, and promotes the newness and sincerity that will “[calentar] a la llama saludable del frío de estos tiempos dolorosos,” (78) spoken of in the “Prólogo.” The prologue to Versos libres, entitled “Mis versos” encapsulates Martí’s desire to convey the poetic sentiments he feels within as he encounters the foreign world around him, and the abandonment he feels. He once again asserts the sincerity of his verses as he attempts to escape narrative poetry and endorse a more lyrical voice. The first half of the prologue states: Estos son mis versos. Son como son. A nadie los pedí prestados. Mientras no pude encerrar íntegras mis visiones en una forma adecuada a ellas, dejé volar mis visiones: oh, cuánto áureo amigo, que ya nunca ha vuelto! Pero la poesía tiene su honradez, y yo he querido siempre ser honrado. Recortar versos, también sí, pero no quiero. Así como cada hombre trae su fisonomía, cada inspiración trae su lenguaje. Amo las sonoridades difíciles, el verso escultórico, vibrante como la porcelana, volador como un ave, ardiente y arrollador como una lengua de lava. El verso ha de ser como una espado reluciente, que deja a los espectadores la memoria de un guerrero que va camino del cielo, y al envainarla en el sol, se rompe en alas. (95) Martí’s firm declaration of the authenticity of his verses emphasizes his drive for sincerity in poetry. They are neither borrowed nor loaned from other writers. They are his and came about through the articulation of his visions. For Martí, the primary goal is a manifestation in honorable form of his visions. Poetry is the most admirable means of revealing his visions, even if it is incapable of divulging all of the anguish and hope Martí feels. As he states, if language is unable to “encerrar íntegras [sus] visiones en una forma adecuada,” he allows them to escape, with the knowledge that they will most likely never return. Even though they are lost, however, they still remain respectable, because they were not twisted or manipulated into something else. Essentially, Martí is asserting that what remains in Versos libres does not in any way contradict the sincere vision that they project. If the vision could not be converted to words or articulated in a poem, the reader will never know of them. For Martí, it is better to lose the vision in its pure form than to convert, or rather, distort it into something else. Martí’s comment criticizes the empty poetry of imitation of many of the Hispanic and Spanish American poets of his day. Unlike their verses, his poems are solely his and are tied only to the visions that inspired them. And though he has the ability to “recortar versos,” he restrains himself from changing the authentic vision he first received. Martí problematizes the situation through the language and images he uses in the prologue, that seem to undermine his heroic ideal. By declaring, “Amo las sonoridades difíciles,” he weakens his call for spontaneity. His desire to express difficult sounds demonstrates a conscientious creativity that undercuts the voice of impulsiveness. Martí’s love for difficult sounds, evident in Versos libres, challenges the very honor of his poetry. As he describes the formation of his poetic voice, which now seems to be more of a creation than an inspiration, he uses an accumulation of metaphorical images 10 (sonoridades difíciles/ verso escultórico/ porcelana/ ave/ lengua de lava/ espada reluciente/ un guerrero/ el sol/ alas), that articulate Martí’s cognizance of his own inventive powers. Instead of witnessing the transcription of the incarnate manifestation of Martí’s vision, we are left with a series of difficult sounds and sculptured verses that no longer resemble the poet’s original revelation. Although Martí repetitively reasserts the authenticity of his poetry, he continually contradicts himself as he undermines his drive for spontaneity in poetic creation: Tajos son éstos de mis propias entrañas —mis guerreros—. Ninguno me ha salido recalentado, artificioso, recompuesto de la mente; sino como las lágrimas salen de los ojos y la sangre sale a borbotones de la herida. No zurcí de éste y aquél, sino sajé en mí mismo. Van escritos, no en tinta de academia, sino en mi propia sangre. Lo que aquí doy a ver lo he visto antes (yo lo he visto, yo), y he visto mucho más, que huyó sin darme tiempo a que copiara sus rasgos. —De la extrañeza, singularidad, prisa, amontonamiento, arrebato de mis visiones, yo mismo tuve la culpa, que las he hecho surgir ante mí como las copio. De la copia yo soy el responsable. Hallé quebrados los vestidos, y otros no y usé de estos colores. Ya sé que no son usados. Amo las sonoridades difíciles y la sinceridad, aunque pueda parecer brutal. His emphatic affirmation that his poetry is sincere and spontaneous, that his verses run from him like tears from one’s eyes, duly asserts the legitimacy of his writing while simultaneously critiquing his contemporaries. He claims that, unlike other contemporary poets from Spain and South America, his poetry is not an artificial re-warming of reworked ideas from his mind. They are the written manifestation of the visions that only he has seen. This prophetic role as visionary seer places his poetry at biblical status. His words, like those of Moses, Isaiah, or even John the Revelator before him, are scriptural revelations that give meaning to life “not as the world giveth,” (John 14:26) but as from someone with visionary insight. In an age when “los sacerdotes no merecen ya la alabanza ni la veneración de los poetas, ni los poetas han comenzado todavía a ser sacerdotes!” (“Prólogo” 60), Martí stands as more than a symbolic voice for poetic enlightenment. His poetry exalts him to the status of a priest or a prophet that “[ha] querido ser leal, y si pec[ó], no [s]e avergüenz[a] de haber pecado” (“Mis versos” 96). Such a declaration reaffirms Martí’s design for authenticity, whether or not that goal can be accomplished. As a poetic seer, he is given the right to reduce the visions to written text using the rhetorical colors of language that accentuate his validity as a poetic lover of “las sonoridades difíciles y la sinceridad, aunque pueda parecer brutal.” He excuses neither himself nor his poetry because it is truth, instead of a falsified distortion of it. However, Martí’s bold contention for sincere poetry, which should be “una espada reluciente,” places him—borrowing a Spanish idiomatic expression—between a sword and a wall. His poetry, which cannot fully express his visions without conforming to some sort of meter or versification, falls short of its desired destination. Without demonstrating his poetics through language, his expression of desire for spontaneity becomes a goal never realized. 11 In a completely different draft of a prologue for Versos libres not used by the poet , Martí exemplifies a more Romantic approach to poetry and expresses his frustration with the inadequacy of language to fully communicate his visionary experiences. It opens with a disclaimer that states both the incompleteness of the text as well as Martí’s scorn for his own work. He states, “Éstas que ofrezco, no son composiciones acabadas: son, ay de mí! notas de imágenes tomadas al vuelo” (Obras completas 223). Similar to the fragmented works of the German Romantic writers Schlegel and Novalis, Martí recognizes an incompleteness to his work. He comes to terms with the impossibility of totality, and that all poetic work is incomplete. In this sense, this introduction differs from “Mis versos” in that he openly admits to the insufficiency of his poetic work. He continues, “Yo desdeño todo lo mío: y a estos versos, atormentados y rebeldes, sombríos y querellosos, los mimo, yo los amo” (223). The deficiency of his work, however, draws the poet nearer to its message. Like the poems themselves, Martí feels tormented, dark, rebellious, and incomplete, and therefore bonds with them. His desire to love and pamper them relates to the suffering they both feel and share. The emptiness in his life and his work relate to the deficiencies of language. As he states, “De estos tormentos nace, y con ellos se excusa, este libro de versos” (223). The inability of language to properly convey the “imágenes tomadas al vuelo” is the proprietor responsible for both the birth and the imperfections of Versos libres. Such a declaration affirms Martí’s proposed heroic, spontaneous, and sincere poetry. By insisting upon the fragmentary nature of Versos libres, this prologue, more so than “Mis versos,” reconfirms the authenticity of Martí’s work. Similar to the leading text in Ismaelillo, “Académica,” the first poem of Versos libres, exemplifies Martí’s search for authenticity, laced with difficult sounds and archaism. It is divided into three distinct sections that outline the visionary poetic experience. The opening section reads as follows: 2 Ven, mi caballo, a que te encinche: quieren Que no con garbo natural el coso Al sabio impulso corras de la vida, Sino que el paso de la pista aprendas, Y la lengua del látigo, y sumiso Des a la silla el arrogante lomo:— With the initial calling of the horse, Martí opens with a metaphorical allusion to the caballero from Ismaelillo. By so doing, he draws upon the image he had written of before, the child at play, and opens the doorway to imagining spontaneous poetry. Martí infers that his poetic creation is more a recompilation of his visions than anything else. His role, as the poet, is to perceive the vision and renew it within a linguistic parameter. In other words, he attempts to first grasp the concept of the image and then give it form. Such is the case in this poem as the author attempts to coax the horse into accompanying him so as not to lose the image. He endeavors to rescue the vision from being distorted by other poets, or academics, that will force the words into unnatural structures. Martí appears to remain faithful to his demands of unforced poetry—he abandons all forms of rhyme seen in his other poetry; however, he uses a variety of poetic tools to configure the ideas into the endecasyllable meter to give a poetic flow to the work. Also, he relies 12 upon hyperbaton in order to restructure the verse to conform with the meter he desires. These poetic instruments, combined with archaisms (encinche/ garbo), arrange the words into a pattern that resembles the very idea Martí rejects. His Versos libres begin to lose their freedom as the author binds the images with the structures and poetic tools that disfigure the original vision. Once again, the encoded message of the vision becomes distorted, rather than revealed, by Martí’s inability to project linguistically the image he witnesses. The second half of the poem details the process of sterilization that takes place as poets attempt to conform the unique ideas and visions they receive to empty rhymes and hollow structures. He continues: Ven, mi caballo: Dicen que en el pecho Lo que es cierto, no es cierto: que la estrofa Ígnea que en lo hondo de las almas nace, Como penacho de fontana pura Que el blando manto de la tierra rompe Y en gotas mil arreboladas cuelga, No ha de cantarse, no, sino la pautas Que en moldecillo azucarado y hueco Encasacados dómines dibujan: Y gritan «Al bribón!» —cuando a las puertas Del tempo augusto un hombre libre asoma!— Once again, Martí returns to coaxing the horse into following his lead so that the poet may liberate him. The academics, on the other hand, will discredit the natural instinct of the vision telling him that “lo que es cierto, no es cierto.” The academics bring into disrepute the inspiration, or “la estrofa ígnea que en lo hondo de las almas nace.” Martí uses a number of metaphors, or “estos colores” (“Mis versos” 96) as he calls them, in order to correlate the visionary poet’s writing to a pure fountain that breaks apart the earth below it. Martí reverts back to the use of hyperbaton (fontana pura/ que … rompe … el blando manto de la tierra), thus undermining his project of pure poetry. Perhaps what he is criticizing more than anything is the dulcifying deformation (moldecillo azucarado y hueco) that often takes place in the writing of verse. Martí rejects the formalities of poetry, preferring the rascal (bribón) to the gentleman (dómine), as the true poetic voice, because the rascal infers a sense of unrestrained liberty, whereas the gentleman has conformed to societal norms. The final section of “Académica” begins again with an invitation to both horse and reader to partake of the beauty of natural, liberated, spontaneous poetry. The poem concludes: Ven mi caballo, con tu casco limpio A yerba nueva y flor de llano oliente, Cinchas estruja, lanza sobre un tronco Seco y piadoso, donde el sol la avive— Del repintado dómine la chupa, De hojas de antaño y de romanas rosas 13 Orlada, y deslucidas hoyas griegas,— Y al sol del alba en que la tierra rompe Echa arrogante por el orbe nuevo. The third and final invitation given to the horse requests that the horse arrive “con tu casco limpio,” implying that the vision must be free from the mind. The mind manipulates the original inspiration and converts it into empty verses. Martí’s continued insistence upon the liberation of the poem from the mind accentuates his focus on the need for a purer, or unadulterated poetry. The academic corrupts poetry and destroys the essence and power of the image because he/she recreates the message instead of displaying it. If this manipulation occurs, the poem becomes the “pesares de contagio, tibiedades latinas, rimas reflejas, dudas ajenas, males de libros, [y] fe prescrita” that Martí desires to cast aside. By arriving without distractions from the mind, the horse can comprehend the nature that surrounds it. It remains untouched and pure “donde el sol la aviva” from the academic. The slight jump from the natural scene to the distractions of empty poetry changes in style as well as in theme. Martí, in describing the natural landscape, displays a variety of simple terms and images free from metaphors. This simplified diction approaches Martí’s proposal of spontaneity and sincerity. However, as the poet begins to discuss the rejected aspects of distorted poetry, the words become archaic and ornamental (dómine/ la chupa/ orlada), mingled with metaphors that connote a counterfeit nature (hojas de antaño/ rosas romanas/ hoyas griegas), demonstrating linguistically the differences between the two styles of verse. Martí’s language, which thematically rejects labored verse, succumbs to the problem of metaphorical stylization. He becomes entrapped by the very dilemma that he so passionately rejects. While Martí’s conscious manifestations of theme and style undermine his overall project towards an uninhibited spontaneous poetry, what he still is able to communicate is sincerity. Martí never cowers to the norms and standards established by his Spanish speaking contemporaries that reveled in the imitation of their European neighbors. Instead, he justifies his poetry by relating the anguish, anxiety, fear, and frustration that he feels in a strange world. Martí uses his poetry as a means of creating an unprecedented literary standard in Spanish American poetry through the renewal of “la otra tradición española” (Paz 502). And while those who would follow him would have very little knowledge of his ethical poetic voice, Martí raises a type of Mosaic staff that he hoped would heal poetry. His simplicity and sincerity, which overshadow his undermining argument for spontaneity, can be seen, from the image of the child in “Príncipe enano” to the empty cups in “Amor de ciudad grande.” This voice of sincerity exemplifies Martí’s overarching mode of rupture that distinguishes him from the Spanish and Spanish American Romantics before him, and the modernistas that would follow him. Among all of these writers, Martí’s mode of rupture is genuine, and pertains solely to him, making him a modern among the modernistas. Martí’s proposal, while bold, seems nearly impossible for the poet to achieve. But it is this boldness, this sharp contrast from the writing he rejects, which defines his ethical view of poetry. This model for a new poetry is merely his idea of what we are capable of attaining, simply due to the fact that the mind has the ability to conceive it. As he states, “La mente no podría concebir lo que no fuera capaz de realizar” (Ensayos 76). 14 And perhaps, by conceiving such an intrepid transition for the future of poetry, he ultimately passes the apostolic torch of poetry to those who will realize his vision of liberated verse. 15 End Notes 1 While critics have often argued over the relationship between Flores del destierro and Versos libres, I will follow the classification given in the Obras completas de José Martí published by Letras Cubanas which classifies Flores del destierro as part of Versos libres. 2 Most often used as the prologue for Flores del destierro, the Obras completas de José Martí published by Letras Cubanas classifies this prologue as merely another draft, and includes it in the appendix. 16 Bibliography Antología crítica de la poesía modernista hispanoamericana. Ed. José Olivio Jiménez. Madrid: Ediciones Hiperión, S.A., 1994. Antología de la poesía hispanoamericana contemporánea 1914-1987. Ed. José Olivio Jiménez. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2004. La prosa modernista hispanoamericana: introducción crítica y antología. Ed. José Olivio Jiménez and Carlos Javier Morales. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1998. The Cambridge History of Latin America. Ed. Leslie Bethell. Vol. IV. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1984. The Cambridge History of Latin America. Ed. Leslie Bethell. Vol. V. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1986. Azam, Gilbert. El modernismo desde dentro. Barcelona: Editorial Anthropos, 1989. Brotherston, Gordon. Latin American Poetry: Origins and Presence. New York: Cambridge UP, 1975. Calinescu, Matei. Five Faces of Modernity. Durham: Duke UP, 1987 Comte, Auguste. Auguste Comte and Positivism: The Essential Writings. Ed. Gertrud Lenzer. New York: Harper & Row, 1975. Darío, Rubén. Autobiografía de Rubén Darío. Barcelona: Linkgua Ediciones, 2003. ---. Azul… / Cantos de vida y esperanza. Ed. José María Martínez. Madrid: Cátedra, 2000. ---. Páginas escogidas. Ed. Ricardo Gullón. Madrid: Cátedra, 1999. De Man, Paul. “Literary History and Literary Modernity.” Blindness & Insight: Essays in the Rhetoric of Contemporary Criticism. New York: Oxford UP, 1971. Hegel, G. W. F. Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Outline and Critical Writings. Ed. Ernst Behler. New York: Continuum., 1990. Henríquez Ureña, Pedro. Las corrientes literarias en la América hispánica. México D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1949. Jrade, Cathy L. Modernismo, Modernity, and the Development of Spanish American Literature. Austin: U of Texas P, 1998. ---. Rubén Darío and the Romantic Search for Unity: The Modernist Recourse to Esoteric Tradition. Austin: U of Texas P, 1983. Kirkpatrick, Gwen. The Dissonant Legacy of Modernismo. Berkeley: U of California P, 1989. Kuhnheim, Jill S. Gender, Politics, and Poetry in Twentieth Century Argentina. Gainesville: UP of Florida, 1996. ---. Textual Disruptions: Spanish American Poetry at the End of the Twentieth Century. Austin: U of Texas P, 2004. Lehmann. A.G. The Symbolist Aesthetic in France. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1968. Lugones, Leopoldo. Obras completas III: Odas seculares. Ed. Pedro Luis Barcia. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Pasco, 2000 Martí, José. Ensayos y crónicas. Ed. José Olivio Jiménez. Madrid: Cátedra, 2004. ---. Ismaelillo/Versos libres/Versos sencillos. Ed. Ivan. A. Schulman. Madrid: Cátedra, 2001. ---. Poesía completa. Ed. Carlos Javier Morales. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1995. 17 Nervo, Amado. Antología poética e ideario. México D.F.: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, S.A., 2005. Paz, Octavio. Obras Completas I: La casa de la presencia. Barcelona: Galaxia Gutenberg, 1999. ---. Obras Completas II. Excursiones/Incursiones, Fundación y disidencia. Barcelona: Galaxia Gutenberg, 2000. Santí, Enrico Mario. Pensar a José Martí: Notas para un centenario. Boulder, CO: Publications of the Society of Spanish and Spanish-American Studies, 1996. 18