Address Forms in Castilian Spanish: Convention and Implicature

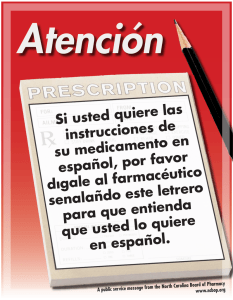

Anuncio