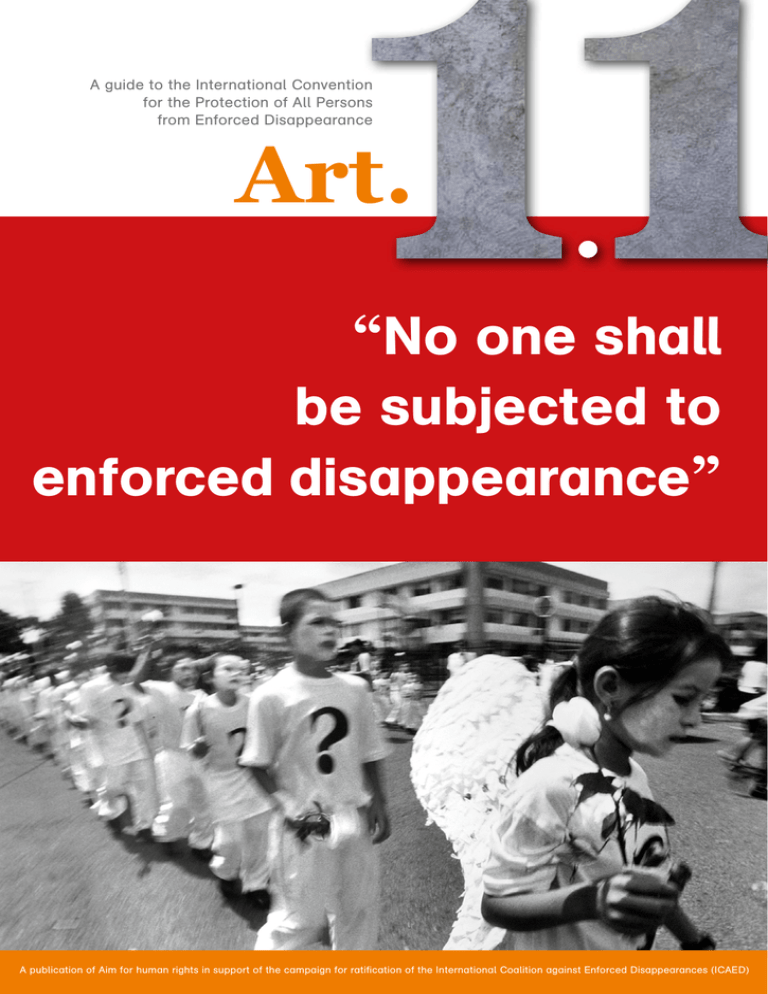

No one shall be subjected to enforced disappearance

Anuncio