An Essay on the Conflict between Access and Excellence: Some

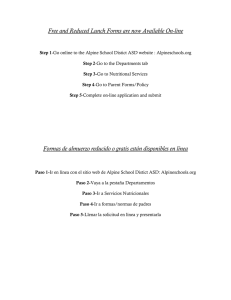

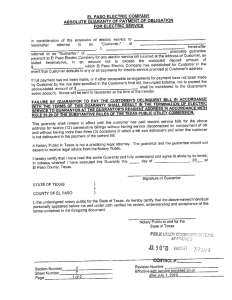

Anuncio

An Essay on the Conflict between Access and Excellence: Some Perceptions by New Faculty By Philip I. Kramer Rodolfo Rincones James W. Satterfield, Jr. Richard D. Sorenson The University of Texas at El Paso Educational Leadership and Foundations Department Contact Information: Dr. Philip I. Kramer The University of Texas at El Paso 500 West University Avenue Education Building, Room 507 El Paso, TX 79968 USA Phone: (915) 747-7591 Facsimile: (915) 747-5838 E-mail: [email protected] 2 An Essay on the Conflict between Access and Excellence: Some Perceptions by New Faculty Introduction The purpose of this essay is to describe and evaluate one Hispanic-serving research university’s efforts to provide relatively open student access to the university and its academic programs and degrees while, at the same time, promoting academic excellence for its students. Much of the literature (e.g., Braxton & Nordvall, 1985; Braxton, 1993; Orfield, 1990; Blanchette, 1997) has described access and excellence as a conflict or a challenge. Strike (1985) for example, said that “the apparent conflict between excellence and equity” underlies a “more real and more fundamental tension between the aspirations embedded in two different sets of purposes for education” (p. 415). As faculty members, we frequently discuss the challenges of “managing” open student access and high expectations of student academic excellence (i.e., high rigor) as a game of academic tug-of-war. The push for greater academic excellence (i.e., higher standards, more student selectively, “better” prepared graduates) is typically met by the pull for continued open access and equity (e.g., keeping admission standards lower to ensure broad student participation and equity in academia) of underrepresented groups (i.e., minorities, women, students from low socio-economic groups). We intend to examine the effects of our institution’s joint goals of access and excellence by primarily describing how the authors--all untenured professors in a graduate education program--experience the issues of teaching and learning in the community and in the classroom. Specifically, we will describe the university and its community. Second, we will explore how access and excellence, vis-à-vis the teaching and learning process, is affected by economic globalization. Third, we examine how the joint goals of access and excellence challenge the 3 institution and its faculty. Fourth, we describe the effort to develop institutional capacity and capital. Finally, we question return to the discussion about what we think are the purposes for education (Strike, 1985) and speculate about whether our educational goals are in harmony or in conflict with the goals of the institution. The University and its Community In 1914, the Texas School of Mines and Metallurgy was opened in El Paso, Texas. In 1919, the institution became part of the University of Texas System and was renamed Texas Western College. Today, the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) (renamed again in 1967) is a Doctoral/Research-Intensive university located on the largest bi-national metropolitan area along the U.S./Mexico border. Ciudad Juarez, Mexico is a few hundred meters from the southern edge of the campus. The New Mexico-Texas border is less than 20 miles northwest of the campus. UTEP, like the greater west Texas/southern New Mexico Borderplex region, is overwhelmingly Hispanic. Many students, faculty, and staff speak and write in both Spanish and English. There are a number of choices for higher education in this Borderplex region of more than 3 million people. Within an hour’s drive, one can find a proprietary, for-profit university, a public community college in El Paso, and a research university in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Across the border, in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, there are eight universities (four public and four private). However, the community is overwhelmingly poor: the 1999 median per capita annual income for El Paso County, for example, was U.S. $13,421 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004). The community is also under-educated; in the same year, only 65.8 percent had obtained a high school diploma and only 16.6 percent had obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004). 4 UTEP plays an important role in the community. Many in El Paso see education, particularly higher education, as the means for individuals to pull themselves out of poverty and for the community to increase the opportunity and equity of its citizens. In El Paso, higher education is cherished as both a public and a private good. The internal and external stakeholders of the university are aware of the important role the university plays in the community. They are also aware of the substantial educational achievement gaps between Caucasians and historic minorities in Texas (Linton & Kester, 2003) and the nation. Nationally, the Hispanic high school drop out rate “is quite grave and…has serious long-term implications for the education system, Latino communities and the nation as a whole” (Fry, 2003, p. iii). The stakeholders of the university are familiar with the poor rates of completion of undergraduate college degrees by Hispanics and realize that Hispanics fall far behind the college completion rates of other racial and ethnic groups (Fry, 2002). Our department’s most important stakeholder group-our graduate students-are well aware that national Hispanic enrollment in graduate school is very small. According to Fry (2002), “Among 25- to 34-year-old high school graduates, nearly 3.8 percent of whites are enrolled in graduate school. Only 1.9 percent of similarly aged Latino high school graduates are pursuing postbaccalaureate studies” (p. 4). In a recent Pew Hispanic Center (2004) report, researchers found that Hispanic participation in postsecondary education was (and is) both less intense and at lower academic levels than other ethnic groups. The report noted, Nearly 1.7 million Hispanic students were enrolled in our nation’s 4,100 degreegranting colleges and universities in fall 2002. A big share of these students, 87 percent, are undergraduates (rather than graduate or first-professional students). In 5 comparison, undergraduates make up 81 percent of all white college students (p. 2) It is in this context that UTEP has made a commitment to both student access and institutional excellence. We are “increasingly recognized as a model in demonstrating that a university with a fundamental commitment to access can also achieve high levels of excellence in academic programs and research” (The University of Texas at El Paso, 2004, paragraph 4). According to the university’s vision statement, “the UTEP community-faculty, students, staff, and administrators-commits itself to the two ideals of excellence and access” (The University of Texas at El Paso, 2004, paragraph 2). According to a recent report by the Washington Advisory Group (2004), the university [UTEP] has nearly $33 million in external research funding, 11 doctoral programs, and a student population that is approximately 70% Hispanic, reflecting the demographic makeup of the region in which UTEP is located. The University is committed to providing access to a high quality education and to excellence in research and teaching. It rejects the traditional assumption that universities that aspire to excellence in research and graduate programs cannot also foster access to undergraduate education by students from a wide range of backgrounds. Given the increasingly recognized importance of engaging the Hispanic population in higher education in general and in science and engineering in particular, UTEP’s mission–to provide both access and excellence–is of national, as well as regional, importance p. 58 Teaching and Learning at the University in a Globalized Context Education is a highly social activity. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the dynamics of society and society’s impact on education. The environment in which universities 6 operate today forces teaching and learning to mimic the demands of the larger context-the demands of certain groups in leadership positions. The discussion about access and excellence takes place at the societal level and in turn is reflected in the university’s core functions of teaching and learning. With this perspective in mind, one may then pose questions such as how can we best approach the study of such complex relations between society and the university? What are the values behind access and excellence? How do the antinomies of access and excellence generate conflicts and competition in the confined spaces of the university, a department, or a program? How can faculty and students best negotiate the contradictory effects of access and excellence? For this paper, we try to explore how untenured faculty members at a Hispanic-serving American research university make sense of and adapt to the shifting mission of their university and to specifically understand how the whirlwind of institutional change affects the teaching and learning process. Traditionally, universities have been sites where multiple frames of understanding and competing discourses meet. These discourses, however, have originated in the larger context of society, some of which tend to be hegemonic. Faculty and students are infused over time with some of these hegemonic discourses (as well as non-hegemonic courses). Bourdieu’s concepts of field and habitus (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 16) help to conceptualize the interplay of society and education and how the predominant discourses are set at the individual and organizational levels. Thus, universities can be conceived as a field. A field is defined as the space in which forces clash and struggle with each other; “a field is simultaneously a space of conflict and contradiction” which “consists of a set of objective, historical relations between 7 positions anchored in certain forms of power” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 16). For this discussion, the issues that clash inside the University are access and excellence. Habitus “consists of a set of historical relations “deposited” within individual bodies in the form of mental or corporeal schemata of perception, appreciation, and action” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 16). Thus, the understanding of the functioning of the field is facilitated by the habitus, which represents a set of tools (knowledge) and skills an individual acquires from and uses in the field to function effectively. The concept of habitus, then, can shed some light into the behaviors and actions of faculty members and students, either individually or collectively. Habitus is legitimized through the power structure of society or the organization. The argument can be made then that the discourse of access and excellence have been made an integral aspect of faculty and students’ frames of mind to the point that these terms are not scrutinized as they should. But what are these terms? Where do they come from? Both of these terms acquired relevance in the last two decades, more precisely since globalization and neoliberalism were coupled. Harvey (2000) defines globalization as a process whereby hegemonic ideologies such as neoliberalism makes full use of “geographical reorganization (both expansion and intensification)” (p. 54), engages in post-Fordist production, flexible accumulation, and free flow of capital throughout the world. Globalization has always been a specific project of particular powers to gain benefits and wealth. According to Harvey (2000), capitalist production has always produced “uneven geographical development” (p.68) characterized by “geographical differences in ways of life, standards of living, resource uses, relations to the environment, and cultural and political forms” (p.77). It seems apparent that two of the consequences of globalization are the segmentation of geographical areas and sectors of society within geographical areas, and the emergence of new 8 forms of production and social organization. Hence, the world is transformed by those who globalize, those who are globalized, and those who are left out (Hallak, 1998). When vast geographical areas are left out of globalization, such as the one El Paso is located in (southern border of the United States), it offers competitive advantages under the post-Fordist form of production. In the 1990s, El Paso and Ciudad Juarez (twin city on the Mexican side of the border) became the Mecca of the assembly (maquila) industry, mainly because low wages and easy and relatively inexpensive transportation routes (time-space compression). With the maquila industry (an arguably prototypical type of post-Fordist production model) came the discourse of standards, quality, efficiency, and excellence. These are terms that have been “deposited” within faculty and students. In fact, it is common to hear educators use these terms in their daily discourse. These terms have been fully imported into education without any serious scrutiny as to their precedence and their implicit meaning. Today, the identities of universities are tied to the meaning of these terms, and by incorporating the discourse of the production sector, educational organizations are moving away from being the place where disparate discourses are presented, discussed, and tolerated. The discourse of excellence and efficiency move the university more toward homogeneity and standardization of functions. In other words, universities are becoming extensions of the corporate state. Thus, under this new vision, the university gains confidence when self-identity is confirmed by similar others (accrediting organizations) and the market. Conflicting views are created when contradictory terms such as access and excellence are used simultaneously. Each one of these concepts originated in a different philosophical perspective. Access, for example, comes from liberalism, which strives for equity and justice, while excellence is an empty concept that requires a relative definition every time it is used. 9 But what are the implications of the discussion above for untenured faculty? We would argue that the implication of framing the functions of the university in the context of neoliberalism brings up the perennial questions of access, equity, and relevance. We cannot postpone the questioning of the status quo in society and its organizations. Faculty and students must reclaim the conditions of realizing the university as suggested by Barnett (2000). We must engage in critical interdisciplinary, collective self-scrutiny, purposive renewal, move borders, engage with multiple communities, and endorse communicative tolerance (Barnett, 2000). Institutional Challenges In its ninety-year history, UTEP has had remarkable (and compressed) institutional growth. Such rapid growth and change in the institutional mission has meant that students, faculty, staff, administrators, and the community have had to grow and adapt much as the university has had to grow and adapt; as the expectations and perspectives of the institution change, the expectations and perspectives of students, faculty, and staff, and the community must also change. Today, UTEP continues to metamorphosis. Plans are to move UTEP, within a 10 to 15 year period, from a Doctoral/Research-Intensive to a Doctoral/Research-Extensive institution. As it becomes a Doctoral/Research-Extensive institution, UTEP seeks to continue serving as an urban university in a minority community, become a preeminent national research university, and achieve recognition as the national center for understanding and solving U.S./Mexico border issues. This goal, like any other institutional goal, will be met with challenges along the way. It is up to each institutional level to help the university's goal. Faculty Challenges 10 According to Zambroski and Freeman (2004), “transitions between academic settings require new faculty members to develop expertise consistent with the institutions’ specific missions. Even those faculty members considered experts in their field must adapt to the challenges of new work settings” (p. 104). Adaptation includes teaching a new and more rigorous curriculum, greater research and publication requirements, and different service obligations. As a result, the nature of tenure and promotion changes; new faculty may have come in with one set of expectations for tenure and promotion, and because of institutional change, faculty must quickly adapt or find themselves in jeopardy of not receiving tenure. As UTEP has begun to put more emphasize on the importance of research and theory to facilitate its transition to a Doctoral/Research-Extensive status (and the need to create a more rigorous academic culture of teaching and research), some students have questioned the value of what they deem as swinging further away from practice. Some students (and some faculty) have questioned the new emphasis on theory and practice. The challenge of integrating research, theory, and practice is of longstanding interest primarily to educational researchers, university professors, and policy makers. Prior research has indicated that many classroom teachers and administrators (who typically rise from the ranks of classroom teaching) do not appreciate the potential contribution of research and theory to classroom-based instruction and general school improvement interests. As individual faculty, we find nothing wrong with furthering their career objectives. Moreover, as faculty, we know that students everywhere have a practical motivation for going to college. Yet, there are times when we pine (as most faculty everywhere probably do) for more students who are as interested in research as they are in the practical importance of a credential. 11 Collectively, we want students to understand, appreciate, and use research to inform practice and practice to create the need and the opportunity for research. Development of Intellectual Capital and Capacity The translation of the university’s vision statements is that access and excellence are not mutually exclusive. The belief is that it is possible to have a university deeply committed to access and institutional excellence. Arguably, broad access means that there is a greater range of student abilities, skills, and knowledge. We assume the ability range of our students is far wider than at more selective research-intensive universities. Our institutional mission to welcome students of varying abilities is not one that other institutions have adopted. Our flagship institution, the University of Texas at Austin, offers no developmental or remedial courses. It appears that the two apparent extremes of access and excellence that continually pull for the attention, resources, and indulgences of our stakeholders (including ourselves), can indeed coexist. Some researchers have argued that academic rigor and excellence increases as student selectivity increases. Braxton and Nordvall (1985), for example, found evidence to suggest that institutional selectivity is “an indicator of institutional quality” (p. 550). Furthermore, Braxton (1993) said “undergraduate admission selectivity is a common defining characteristic of the academic quality or excellence of a given college or university” (p. 657). Our experiences indicate a different conclusion than Braxton and Nordvall-a university low on the student selectivity scale can very much be a place of great institutional (and instructional) quality. Our admittedly anecdotal experiences, however, imply that many variables-in addition to the selectivity variable-influence student rigor, institutional quality, and excellence. As faculty members, we see our students and ourselves struggle with what Schön (1995) described as the 12 “dilemma of rigor or relevance” (paragraph 11) in modern research universities. For Schön, the norms and “prevailing epistemology” (paragraph 8) of research universities is such that these institutions strongly prefer to be institutions of “technical rationality” (paragraph 7) where the coins of the realm are theory, research, and rigor rather than, for example, the scholarship of integration and application as identified by Boyer (1990). Schön said, there is a high, hard ground overlooking a swamp. On the high ground, manageable problems lend themselves to solution through the use of researchbased theory and technique. In the swampy lowlands, problems are messy and confusing and incapable of technical solution (paragraph 11) Schön was arguing for a new form of scholarship that required a new institutional epistemology that would incorporate and legitimize the research of reflective and relevant practice possibly at the expense of some rigor. We, of course, find our concerns to be just the opposite of what Schön described. Today, we are an institution of more practice than theory. However, tomorrow, we will need to be far more in balance-we need to still focus on practice but emphasize more theory and diversify and increase our research productivity. One of our challenges is to find the balance between the “relevant” practitioner and the relevant researcher. A goal, then, is to attempt to legitimize ourselves to both “an environment which includes both a university culture that values basic research and theoretical knowledge and a professional culture of schooling that values applied research and narrative knowledge” (Anderson & Herr, 1999, p. 12). Increasing Faculty, Student, and Departmental Intellectual Capital and Capacity 13 Graduate programs in educational leadership depend on a balance between theory and practice. The theory and practice interrelationship provides the necessary shaping of productive futures through a process of self-renewal (Senge, Kleiner, Roberts, Ross, Roth, & Smith, 1999; Senge, Cambron-McCabe, Lucas, Smith, Dutton, & Kleiner, 2000). To enhance the capacity of change and self-renewal in an organization, we are in the process of involving all parties (e.g., faculty, K-12 practitioner/leaders) in continual and sustained dialogue and decision-making regarding issues of access and excellence. We believe we can change the future. If agents central to the self-renewal effect are recognized as equal partners in this process by acknowledging their professionalism and by capitalizing on their skills and expertise, then essential programmatic change will occur (Darling-Hammond, 1988; Rowan, 1990). The equal partnership proposition involves the active collaboration of graduate program professors and K-12 practitioners when assessing programmatic particulars such as curriculum, course selections, instructional methodologies, assessment techniques and procedures, and other factors regarding access and excellence. Within this model, graduate program faculty must seek out ideas, suggestions, insights, and expertise from not only within their ranks but also from those K-12 leaders who specialize in educational reform and organizational improvement. Thus, the graduate program leaders are not the sole instructional leaders but the “leaders of instructional leaders” (Glickman, 1989, p. 6). The challenge for any organization is to link values and find common ground that encourages positive change. Access to graduate education in the field of educational leadership can become the bridge for developing common values in order to resolve the many complex educational issues. Education remains the key to stimulating diverse populations that have the potential to build the wealth that benefits the economy and prepares for a prosperous future 14 (Butner, Ferguson, Bean, & Huerta, 2001). Promoting graduate education, specifically for minority students, will serve to close the growing economic chasm in today’s society. An important question to ask is, what are the primary functions of graduate education and how can these functions served to benefit all concerned parties (students, professors, and school practitioners)? Areas of consideration include (a) general assessment and the proper direction of change, (b) the prospective supply, demand, and manpower forecast for graduate students, (c) effective responses to current and potential problems, (d) the support of graduate students, (e) resources required for high-quality graduate education, (f) the contribution of the university faculty and school practitioners to the teaching of prospective school administrators, (g) the role of universities and educational leadership departments in confronting the problems of access and excellence in graduate education, and (h) the appropriate rigors and expectations with respect to equal access in graduate education (Kinnick & Ricks, 1990). When seeking to identify the characteristics of a high quality graduate education program as it relates to access and excellence, Lipschutz (1998) relates that contemporary research universities are composed of many autonomous spheres (e.g., undergraduate and graduate education, professional education, faculty research). Analysis reveals that the spheres are interconnected, so when the climate and expectations for intellectual exchange and excellence are improved in one, others can be enhanced, ultimately improving the sense of intellectual community of a department, or for that matter, an entire university. Analysis by Lipschutz (1998) has produced focuses on factors that contribute to excellence in graduate education including the following: (a) academic potential of the students, (b) numbers and capacities of the faculty, (c) the academic culture, norms, and expectations of a department, (d) student advising (e.g., depth, cohesiveness, and breadth of the curriculum), (e) and instructional rigor. 15 Most graduate programs with practicum or internship experiences depend on a network of practitioner leaders in the community to provide access, programmatic expectations, and most certainly supervision. It is valuable for graduate programs in educational leadership to provide for exceptional internship programs. All experiences related to research and work-related activities in the field are value-laden. If an effective practicum or internship experience is required of students, many valuable lessons are possible. One possible lesson is the supervision and essential modeling a qualified school leader or field mentor can provide to a student. Another lesson is the discourse and interaction between school leaders and students that can serve to develop an appropriate level of excellence, potential assess to administrative positions, and hopefully a genuine sense of ethics and professional integrity (Werner, 1985). The equitable distribution of power and authority in a graduate department can affect the quality of programs in schools of educational leadership and the freedom to innovate them (Schneider, 1984). The creation of programs in nontraditional areas, the establishment of relationships with K-12 school leaders, and the recruiting and supporting of graduate students are all positive benefits of increased communication, enhanced departmental climate and collaboration, mentorship of junior faculty, and shared decision-making (Lipschutz, 1998). The research has effectively revealed a notable truism: when all parties participate in the decisionmaking process, the result is equal or relatively equal access to excellent educational opportunities which in turn produces a political power to be wielded by all beneficiaries. O’Banion (1974) discussed implications associated with improving access and excellence in graduate programs. These implications include (a) graduate education must be offered at the convenience of the students served, (b) differing types of degrees or programmatic focuses must be explored, (c) all learning experiences must have practical applications, (d) graduate courses 16 must provide for personal, as well as intellectual rigor and development, (e) graduate education faculty should include as adjunct instructors those professionals who have proven themselves on the job and who provide student access to graduate level instruction beyond the on-campus, traditional program approach, (f) technologically innovative educational delivery systems should be incorporated into the graduate level instructional program, and (g) graduate programs should work in close cooperation with skilled practitioners in public school systems. The principal tool or process available to enforce compliance regarding organizational reform, self-renewal, change, and/or improvement, as well as the advancement of access and excellence for all relates to two essential elements. Namely, these elements are the (a) emergence of a collaborative process whereby all faculty actively, freely, and equally participate in the decision-making process and (b) the formation of an equal and effective partnership between those individuals and entities (e.g., university faculty and public school officials) who are critical stakeholders in the overall success of improved access and excellence. Increasing Institutional Capital and Capacity The University of Texas at El Paso is committed to access and excellence. Student access and excellence is a working reality. Clearly there are some barriers to excellence. For example, approximately two-thirds of our incoming freshmen are enrolled in at least one developmental academic course. However, unlike our flagship institution, we recognize the remediation as an opportunity to establish institutional norms and values. The University of Texas at El Paso’s normative values are representative of a historical process of institutionalization. The desire to change UTEP’s technical core through increasing its research focus is rooted in issues of institutional legitimacy. According to Scott (1995), schools gain legitimacy by their connection to the larger social system. We believe that UTEP’s access 17 and excellence ideology is also rooted in the normative institutional pillar. Norms help establish institutional goals and objectives. Scott (1995) defines norms as valid means to ends. Access and excellence are the means; educating and graduating a large Hispanic student population are the ends. We must not forget, however, that the repercussions of a normative system centered on access and excellences can be limiting. Scott notes that norms can be confining, and, at the same time, empowering. This institutional struggle between access and excellence and a desired shift to a research-extensive institution puts untenured junior faculty in a difficult position. Academically, we operate within our normative structure by concentrating on teaching, advising, and making sure the bulk of our students pass the Texas Examination of Educator Standards (TexES). (TexES is our state certification for public school administrators). Yet, the emphasis placed on increasing the percentage of students passing this exam decreases the emphasis placed on our research and writing. In short, it is difficult to do the things we need to do to earn tenure. What we do currently will soon be at odds the institutional change. Although we recognize and support the forthcoming institutional change, we recognize the regulatory nature of education will present a challenge. The regulative institutional pillar defines what the institutional rules are and helps regulate behavior. One would think academic freedom would be an issue here. Yet, the unwritten and informal rule is, “You are here to make sure each student who is taking the TexES successfully passes the examination.” Therefore, if part of what we teach is seminal knowledge in the field, it does not matter what we do (or don’t do) unless we can align our course objectives to what is on the test. Any deviation from this may cause us to be seen as not being a member of the team. According to North (1990), institutions are perfectly analogous to the rules of the game in a competitive team 18 sport. That is, they consist of formal written rules as well as typically unwritten codes of conduct that underlie and supplement formal rules . . . the rules and informal codes are sometimes violated and punishment is enacted (p. 4). Another factor that makes access and excellence difficult is the nature of our governance structure. The nature of our department and the college of education, for that matter, gives way to the state’s academic desires-not because we want to but because we must give way due to the regulatory nature of education. Williamson (1985) argued that the regulative aspect of institutional structures made governance an institution’s primary focus. Scott (1995) said “the state is simply another organizational actor: a bureaucratically organized administrative structure empowered to govern . . .” (p. 93). The amount of control the state has in the governance structure will not change. Colleges of education will lament for years to come because we are not a profession. True professions manage through cognitive and normative methods (Scott, 1995). This further creates a dichotomy within teaching and learning. In addition, it establishes the language, symbols, and signs we use in our educational activities and provides insight into what we value. Because social reality is socially constructed, we attach meanings to these things and over time, they become institutionalized. Scott (1995) said, “they are employed to make sense of the ongoing stream of happenings” (p. 40). UTEP’s desire to makes the transition to a research-extensive university cannot ignore the absence of cultural/environmental perspectives. If those perspectives are absent, the argument can be made that the transition is to further obtain legitimacy within the larger social system. In education schools are the dependent variable; they are dependent upon the communities in which they reside. As previously mentioned, only 65.8% of El Pasoans 19 graduated from high school and only 16.6% of the population obtained bachelors degrees. Given the norms and values of our regional community in the southwest, as well as the national academic community, we anticipate a difficult, yet challenging transition. To facilitate this transition, we must be aware of not only the concomitant demands placed upon individual faculty, staff, and students and the institution itself, but also how those connected demands between person and institution can and should be mutually beneficial. 20 References Anderson, G. L., & Herr, K. (1999). The new paradigm wars: Is there room for rigorous practitioner knowledge in schools and universities? Educational Researcher, 28(5), 1221. Barnett, R. (2000). University knowledge in an age of supercomplexity. Higher Education, 40(4), 409-422. Blanchette, C. M. (1997). Challenges in promoting access and excellence in education. Washington, DC: Department of Education. Bourdieu, P. & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Washington, DC: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Braxton, J. M. (1993). Selectivity and rigor in research universities. The Journal of Higher Education, 64(6), 657-675. Braxton, J. M., & Nordvall, R. C. (1985). Selective liberal Arts Colleges: Higher quality as well as higher prestige? The Journal of Higher Education, 56(5), 538-554. Butner, B. K., Ferguson, R., Bean, D. L., & Huerta, M. (2001). Minority participation in graduate education: A social and economic imperative. Washington, DC: ERIC. Darling-Hammond, L. (1998). Policy and professionalism. In A. Lieberman (Ed.), Building a professional culture in organizations (pp. 55-77). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Fry, R. (2002). Latinos in higher education: Many enroll, too few graduate. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. 21 Fry, R. (2003). Hispanic youth dropping out of U.S. schools: Measuring the challenge. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. Glickman, C. (1989). Has Sam and Samantha’s time come at last? Educational Leadership, 46(8), 4-9. Hallak, J. (1998). Education and Globalization. Paris: UNESCO-IIEP. Harvey, D. (2000). Spaces of hope. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Kinnick, M. K., & Ricks, M. F. (1990). The urban public university in the United States: An analysis of change, 1977-1987. Research in Higher Education, 31(1), 15-38. Linton, T. H., & Kester, D. (2003). Exploring the achievement gap between White and minority students in Texas: A comparison of the 1996 and 2000 NAEP and TAAS eight grade mathematics test results. Retrieved August 27, 2003, from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v11n10 Lipschutz, S. S. (1998). Improving the climate for graduate education at a major research university. CGS Communicator, 21(4), 1-3. North, D.C. (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. O'Banion, T. (1974). Alternate forms of graduate education for community college staff: A descriptive review. Paper presented at the Conference on Graduate Education and the Community College, Warrenton, Virginia. Pew Hispanic Center. (2004). Hispanic college enrollment: Less intensive and less heavily subsidized. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. 22 Rowan, B. (1990). Commitment and control: Alternative strategies for the organizational design. In C. B. Cazden (Ed.), Review of Research in Education: Vol 16 (pp. 353-389). Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association. Schneider, B. L. (1984). Graduate programs in schools of education: Facing tomorrow, today. New Directions for Higher Education, 46, (pp. 57-63). Schön, D. A. (1995). The new scholarship requires a new epistemology. Retrieved February 20, 2004, from http://0-search.epnet.com.lib.utep.edu:80/direct.asp?an=9512100782&db=aph Scott R. W. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Senge, P., Cambron-McCabe, N., Lucas, T., Smith, B., Dutton, J., & Kleiner, A. (2000). Schools that learn: A fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about education. New York: Doubleday/Currency. Senge, P., Kleiner, A., Roberts, C., Ross, R., Roth, G., & Smith, B. (1999). The dance of change: The challenges to sustaining momentum in learning organizations. New York: Doubleday/Currency. Strike, K. A. (1985). Is there a conflict between equity and excellence? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 7(4), 409-416. Shulman, L. S. (1999). Taking learning seriously. Retrieved February 6, 2004, from http://0vnweb.hwwilsonweb.com.lib.utep.edu:80/hww/shared/shared_main.jhtml;jsessionid=FX W2OOUHUD0XHQA3DILCFFWADUNBIIV0?_requestid=51586 U.S. Census Bureau. (2004a). El Paso County QuickFacts from the U. S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 20, 2004, from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/48/48141.html. University of Texas at El Paso. (2004). The University of Texas at El Paso vision. Retrieved February 5, 2004, from http://www.utep.edu/admin/index.html 23 Washington Advisory Group LLC. (2004). Report of The Washington Advisory Group, LLC on Research Capability Expansion for The University of Texas System, The University of Texas at Arlington, The University of Texas at Dallas, The University of Texas at El Paso, The University of Texas at San Antonio. Washington, DC: The Washington Advisory Group, LLC. Werner, C. M. (1985). Practical and ethical aspects of field research. Paper presentation. ED263476 ERIC. 1-9. Zambroski, C. H., & Freeman, L. H. (2004). Faculty role transition from a community college to a research-intensive university. Journal of Nursing Education, 43(3), 104-106.