this PDF file - Linguistic Society of America

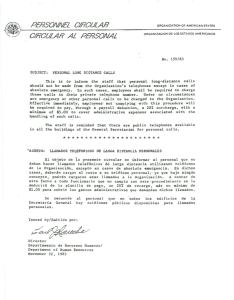

Anuncio