The Pedregal Gardens and the Human Condition

Anuncio

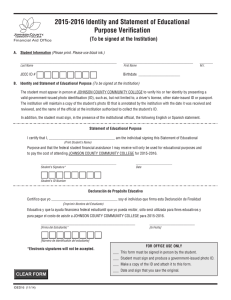

International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 www.seipub.org/ijss doi: 10.14355/ijss.2016.04.001 The Pedregal Gardens and the Human Condition Fernando Curiel Gámez Tecnologico de Monterrey, Campus Puebla. [email protected] Abstract One of Barragán’s most famous landscape works is the Pedregal Gardens, built between the 1940s and 50s. During this time, Barragán entered into one of his most important creative periods as an architect, which coincided with the generally critical reviews of modern architecture that appeared in the 1920s and 1930s. Barragán, like some architects of his time, practiced through an ideological and philosophical framework which challenged concepts of mechanistic, functionalist and technological utopias that were current in architectural ideas of that era. Today, at Barragán’s House‐Studio, his personal library is maintained as part of his personal archive. Barragán’s library is composed of nearly 2,100 books and 640 magazines on many subjects, such as architecture, the arts, literature, philosophy, anthropology, and many more. A complete analysis of his personal library revealed that Barragán left a form of marginalia in many books and magazines: comprising underlined paragraphs, notes, folded pages, photos and whole pages of magazinesʹ. This evidence in Barragán’s books and magazines permits a large number of conclusions on the philosophical and moral doctrine that he took from authors such as Marco Aurelio, Pascal, Aldous Huxley, and Cyril Connolly, which defined the ideology explored in his architectural and landscape works during the 1940s and 1950s. This paper analyzes the multiple ideas that Barragán took from these authors, thus contributing to a better understanding of the ideological discourse in Barragán’s work, especially the Jardines del Pedregal. Keywords Luis BarragÁN’S Library; Architecture and Philosophy; the Pedregal Gardens; Human Condition Introduction By the end of the 1940s, at the same time that Luis Barragán was finalizing a series of landscaping projects such as the Jardines de El Cabrío, the Mexican architect began to develop the property known as the El Pedregal Gardens. From the outset of his career, Barragán was drawn to the characteristics of the region in which this project was developed. In an interview, Luis Barragán gave to the journalist Elena Poniatovska in 1976, the Mexican architect recalled his first impressions from his initial visits to the location: “I have tended to look for emotivity, and my environments are mysterious, magical, and enigmatic. I have always worked around enigma. One example was the fascination that El Pedregal de San Ángel inspired in me. For me, the lava was something incomprehensible. Why these rocks and why, when this all seemed so hostile to others, was I so powerfully drawn to it and compelled to stay there for hours?”1 Barragán’s fascination with the characteristics of El Pedregal and the surrounding area led him to make a very particular intervention. Marc Treib described that, compared with the previous landscaping works that Barragán developed at the beginning of the 1940s, it was the characteristics of the area surrounding El Pedregal themselves that determined his landscaping design decisions. In this way, Barragán subtly transfigured the topography and vegetation to create paths, and squares, spaces for pause and contemplation, taking the advantage of the volcanic rock’s existing walls and recesses. The photographs Tr. by Benjamin Stewart. The Spanish text mentions the following: “He tenido la tendencia a buscar la emotividad, y mis ambientes son el misterio, la magia, el enigma. Siempre he funcionado en torno al enigma. Un ejemplo fue la fascinación que ejerció sobre mí El Pedregal de San Ángel. La lava fue para mí una cosa incomprensible, ¿por qué esas rocas?, y ¿por qué todo eso que a los demás les parecía tan hostil, a mí me atraía tan poderosamente y me invitaba a quedarme horas allí?” Riggen, Antonio, (ed.), Luis Barragán, escritos y conversaciones, Colección Biblioteca de Arquitectura no. 9, El Escorial, El Croquis Editorial, 2000, p. 109. 1 1 www.seipub.org/ijss International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 that Armando Salas Portugal took at El Pedregal at the time bear witness to Barragán’s obsessive desire to capture those environments where illusion, solitude and magic occur in spaces that take form thanks to the contrasts generated among the rock, the smooth texture of the grass, the cloudless skies, the abundance of vegetation and the twisted trunks of completely dry trees2. Also enigmatic are the desolate plazas which appear isolated sculptural elements, whose shadows extending over the smooth pavements emphasize the dramatic nature of the scene. By the mid‐1950s, El Pedregal had garnered a prominent reputation in México. 3 Of the architectural and landscaping works that Luis Barragán came to undertake throughout his career, El Pedregal is, without doubt, one of the most important. From the various critical reflections produced on this work of landscaping, it has been possible to distinguish a clear link between the Pedregal and the metaphysical aesthetic of the Italian painter De Chirico.4 Barragán’s aspiration to transcend the space dedicated to the gardens through landscaped scenes close to the metaphysical poetry of the Italian painter became evident through the work of the photographer and his portraits5. However, there was an additional intention that complemented Barragán’s aspirations for the El Pedregal gardens. In the same way he recreated these idealized metaphysical landscapes through photography, Barragán came to define the nature of a hypothetical inhabitant who would wander through these very gardens. On 6th October 1951, Barragán was invited by the California Council of Architects to give a paper on the El Pedregal gardens. In this paper, titled Gardens for Environment: Jardines de El Pedregal 6 , Barragán described the common lifestyle of the modern man which, from his perspective, had become essentially public. According to this Mexican master, the large majority of people had become accustomed to dining far from their homes. During vacations they frequented clubs, bars or cinemas and, in general, were constantly exposed to mass media such as the radio, television and telephone. In light of this panorama, Barragán asked himself at what time of the day the modern man was able to meditate and allow his imagination to develop creative and spiritual ideas. Attending to this concern, Barragán saw in the garden a manner of returning to man the physical and spiritual rest that would grant him moments of peace and tranquility. For this, he identified the difference between the concepts of the open7 and private garden. From his point of view, open gardens had been created by the public figure, who passes the large part of his time evading his “boredom” in public life. Contrary to the above, for Barragán, the private garden represented the palliative ideal that liberated its users from the animosity of the modern city. In this way, behind the notion that Barragán creates regarding the private garden lies the intention that the public figure from the big city transcend the hostilities derived from his lifestyle, raising his consciousness in such a way that enables him to aspire to spiritual values and authenticity.8 In the same way that Barragán had his artistic references for photographic representation (the discourse on an environment full of metaphysical artistic values), the Mexican architect also arrived at his own moral and philosophical references, which molded the nature of this Cfr. Marc Treib, “Un escenario para la soledad: el paisaje de Luis Barragán”, in, Zanco, Federica, Luis Barragán: La Revolución Callada, Barcelona, Barragán Foundation‐Vitra Design Museum, Ediciones Gustavo Gili, S.A., 2001, p. 126. 3 From the mid‐1940s until the mid‐1950s, the majority of the national and international architectural publications that publicized Luis Barragán’s work focused specifically on the El Pedregal Gardens. The list of the many articles dedicated to this work can be consulted in idem, pp. 305‐306. 2 Keith Eggener, one of the critics who have focused closely on the work of gardens at El Pedregal. He had described the link between the architect and the artist in Eggener, Keith, Gardens of El Pedregal, New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 2000, P.78 5 Said interest can be verified in the personal library of the Mexican architect, in which are highlighted such volumes as Pittori Italiani Contemporari, 12 opere di Giorgio de Chirico, Second Edition by Milione Milano; The early Chirico by James Thrall Soby (1941). In all of these books, Barragán marked the images related to the works of the Italian painter, such as The Evil Genius of a King (1914‐1915), Self‐portrait (What shall I love if not the enigma?), (1911), and The Departure of the Argonauts (1920). Equally, in 1976, Barragán confirmed to the Mexican journalist Elena Poniatowska the metaphysical influence of De Chirico on his architectural work in the following manner: “De Chirico’s landscapes, and those of many surrealists, are characterized by solitude; and many of my environments (…) cannot fail to summon up the solitude of one of De Chirico’s paintings. I do not propose to express solitude, I do not say to myself: What I want is to give the sensation of solitude. No – solitude emerges on its own, spontaneously; it is the first expression of the human being.” Op. Cit, Riggen, p. 119‐120. 6 The Gardens for Environment: Jardines de El Pedregal lecture, which was given by Barragán before the California Council of Architects, was published in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects, vol. 17, no.4, April, 1952. 7 The concepts written in cursive script are used to emphasize the words that Luis Barragán himself used in his speech. 8 Cfr. Speech which Barragán gave to the California Council of Architects and the Sierra Nevada Regional Conference in 1951, in, op cit. Riggen, pp. 36‐40. 4 2 International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 www.seipub.org/ijss hypothetical inhabitant wandering among the gardens at El Pedregal. The moral and philosophical references on which Barragán constructed this inhabitant were very diverse. Currently, the Luis Barragán House and Studio retains part of the Mexican architect’s personal records and his personal library. An analysis of the books and magazines that Barragán collected over the course of his life reveals a multiplicity of themes and the lines along which his reading was directed by his interests and taste. For this reason, the principal aim developed in this paper is to give light to those authors and philosophical works that provided substance to the collection of ideas synthesized by Barragán in forming the ideological basis on which he undertook the landscaping design of El Pedregal. Luis Barragán’s Intellectual Environment Before dealing with the books that influenced him, information described below is the intellectual panorama in which Luis Barragán was operating at the time that he developed El Pedregal. Before arriving to Mexico City, Barragán had participated in editions of the magazine Banderas de Provincias, the principal organ of a group of conservative intellectuals and the clergy in the city of Guadalajara9. Subsequently, when Barragán came to the capital in 1935, the intellectual climate that predominated was characterized by two well‐defined ideological currents: the cardenista and the neo‐orteguista. The group of intellectuals that sympathized both with the philosophical ideas of José Ortega y Gasset and the first existentialist ideological currents in México proclaimed themselves Los Contemporáneos (The Contemporaries), and were directed by Samuel Ramos.10 Furthermore, the ideas of the Spanish philosopher gained great momentum when, thanks to the international policies of President Lázaro Cárdenas, the Spanish Civil War led to the arrival in Mexico of thinkers such as José Gaos, Eduardo Nicol, and Joaquín Xirau, among others. All of these thinkers were welcomed into academic circles and began to take different philosophical positions, which contributed not only to the promotion and discussion of orteguista and German doctrines, but also to the formation of existentialist Mexican thinking.11 Throughout the last years of the 1930s, Barragán had struck up friendships with a diverse range of intellectuals whose work revolved around neo‐ orteguista thinking. Among these should be mentioned Justino Fernández12, Edmundo OʹGorman13 and the Spanish philosopher José Gaos. Consequently, it is likely that the influence of all of these relationships on Barragán resulted in a particular collection of books that, in one way or another, was able to satisfy his diverse intellectual concerns at the time. Philosophy Books Barragán kept close to 43 volumes of philosophy books. This number is small compared with the 2,192 books and 652 magazine editions that comprise the totality of the Mexican architect’s library. Many of the philosophical texts Cfr. Palomar,Verea Juan, Andrés Casillas de Alba, monografías de arquitectos del siglo XX, no. 7, Secretaría de Cultura del Gobierno de Jalisco, Guadalajara, México, 2006, p. 30. 10 Samuel Ramos was an intellectual who, on repeated occasions, expressed his opposition to the socialist policies of Cardenas. In counterpoint to the latter, Ramos introduced a line of thinking directed towards self‐knowledge, retraction and self‐absorption. In itself, this line of thinking presented a fundamental feature for the development of Mexican thinking over the subsequent decades: neo‐orteguism. In this way, he presence of German philosophy publicized in Mexico by the journal Revista de Occidente and the philosophical doctrine of José Ortega y Gasset as divulged through their publications were the principal means by which neo‐orteguism and existentialism was disseminated in Mexico. Romanell, Patrick, The making of the Mexican mind, a study in recent Mexican thought, Lincoln, Nebraska, E.U., University of Nebraska Press, 1952, p. 147. 9 Cfr. ídem. Throughout the 1930s, Justino Fernández occupied himself with the publication of books aimed at the architectural and artistic valuation of a diverse range of people and places found in the Mexican provinces. His best work is found in his reflection on the work of José Clemente Orozco, to whom he was introduced in 1939 by Luis Barragán. In this regard, Justino Fernández wrote the following: ʺI personally met Orozco in 1939, when the architect Luis Barragán introduced me to him one day in the Prendes restaurant. From that day until his death in 1949, we formed a strong friendship, and I believe I can say that I was the friend with whom he shared the most intimacy in those last ten years of his life. ʺCf. Fernández, Justino, Textos de Orozco (Textson Orozco), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (National Autonomous University of Mexico), General Office for Publications., 1983, p. 115. The friendship between Barragán and this art intellectual continued through the 1940s, where the collaboration of Enrique del Moral, Barragán and Justino Fernández himself led to the construction of a duplex house found in the street Santa Mónica no. 13. Cfr. Noelle, Louise, Luis Barragán, búsqueda y creatividad, Colección de Arte no. 49, Primera Edición, México D.F., Dirección General de Publicaciones de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, C.U., 1996, p. 97. 13 Patrick Romanell maintains that there was a close friendship between Justino Fernández and Edmundo OʹGorman. Cf, op. cit. Romanell, Patrick, p. 183. 11 12 3 www.seipub.org/ijss International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 were published at different times over the course of the Twentieth Century. It should also be noted that many of these texts bear Barragán’s notes on their pages. In general terms, 20% of the books from his personal library bear such notes. Barragán was in the habit of appropriating the themes and ideas that most interested him, marking them by folding page corners or underlining phrases or sentences that for him had relevant meaning. Bookmarks were also found in other texts and magazines in which there were illustrations, photographs or other types of documents. Of the 43 books that Barragán kept on the theme of philosophy, thirteen contain pages bearing this type of notation. These features were of great importance, in that they enabled him to deepen his knowledge specifically in those ideas that interested him. Assuming Barragán read the texts during the years close to the books’ publication dates, this bibliography deepens knowledge of certain ideas which Barragán was assimilating, including those on which the Mexican architect reflected in relation to the gardens at El Pedregal in his discourse before the California Council of Architects. Based on the above, an analysis of the books published before 1951 reveals that Barragán underlined and marked paragraphs with content addressing a great variety of themes. However, there is one theme in particular which is common and recurring in those books analyzed below, namely, the theme of the human condition. It is the same which, in essence, comprises a majority of the ideological content that Barragán established in his discourse on the gardens at El Pedregal before the California Council of Architects. For the purposes of this paper, the most representative books were selected. Barragán and the Human Condition The first book reviewed below is by R. Pierre Sanson, and which, published in 1933, is titled La Souffrance et nous. The most relevant examples are those underlined by Barragán in those pages dealing with the theme of human suffering. Sanson maintains that suffering is nothing more than the ideal state that not only encourages profound realization in the life of men, but also provides the means through which they are given place of honor among the principal spiritual forces of the world. Therefore, suffering is the master of life.14 Sanson accepted with pleasure the advances that, up to that moment, science had attained for the benefit of humanity. However, Sanson maintains, scientific progress cannot increase men’s quality of life at the expense of avoiding human suffering. Comfort and distractions impede the spiritual evolution that all human beings are prone to undergo. Therefore, human suffering is irreducible, given that its absence completely annihilates man. Barragán underlined the following quote (Fig. 1): ʺThis comfort exempts us from all effort and all shame, it makes us run the risk of causing ourselves to regress. It threatens us with the dissolution of our highest faculties and the obstruction of our link with life. (…) ʺBetter to die than rotʺ (...). Perhaps exaggerated comfort will not cause us to die, but we do rot. Suffering is worth one thousand times more than the manner in which comfort acts on our souls, (…)ʺ15 Source: Luis Barragán’s library in Casa‐Museo Luis Barragán in Mexico City. FIG. 1: BARRAGAN’S UNDERLINE IN PAGE 66‐67 IN R.P. SANSON’S LA SOUFFRANCE ET NOUS, 1933. Cfr. Sanson, R.P, La souffrance et nous, Paris, Flammarion, 1933, p. 41. Ibidem, p. 66‐67. Tr. by Benjamin Stewart. This French text mentions the following: ʺ(...) ce confort que essaye de nous exempter de tout effort et de toute peine risque dʹavoir pour conséquence une formidable régression; il menace de dissoudre nos plus hautes facultés et dʹarrêter lʹélan même de la vie. ʺPlutôt mourir que pourrir. (...) le confort à outrance ne nous ferait peut‐être pas mourir, il nous ferait sûrement pourrir. Mieux vaut mille fois la souffrance, qui, agissant un peu sur nos âmes à la façon des parfums utilisés pour lʹembaumement des corps, les préserve de la corruption de ce tombeau quʹest la vie de mollesse et dʹégoïsme.ʺ 14 15 4 International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 www.seipub.org/ijss In terms of the thinkers from stoic philosophy, Barragán gave special attention to Marcus Aurelius. The books that were reviewed were Thoughts of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, Epictetus’ Handbook, the Tablet of Cebes, a compilation of writings by Joaquín Delgado (1929), and Soliloquies (1945). For Barragán, these texts abounded with the strength that every stoic must maintain before the fragility and inconsistency of the human condition. 16 The Mexican architect highlighted the maxims which Marcus Aurelius valued, such as virtud meritoria – the capacity of the stoic to withstand the suffering that comes with all of life’s misadventures. Additionally, from Marcus Aurelius’ point of view, the stoic possesses sufficient strength to resist, among other things, the pleasures in life. Barragán highlighted the following (Fig. 2): ʺXXXIV‐ If the idea of some pleasure pleases you, then, as always, take great care with it, lest you not take the wrong path. (…) Then, consider two different periods: the time for which you enjoy this pleasure, and the time after having enjoyed it, when you will regret it and suffer remorse for it. On the contrary, see what will be your satisfaction, what esteem will you have for yourself, if you abstain from this pleasure.ʺ17 Source: Luis Barragán’s library in Casa‐Museo Luis Barragán in Mexico City. FIG. 2: BARRAGÁN’S UNDERLINE IN PAGE 276‐277 IN DELGADO, JOAQUÍN, PENSAMIENTOS DE MARCO AURELIO, MANUAL DE EPICTETO Y CUADRO DE CEBES, 1929. In turn, Barragán extracted from the Epictetus’ Handbook the idea that the momentary condition of those objects which inspire pleasure distracts the senses, especially in those who adulate vanity.18 Barragán also deepened his knowledge of the ideas collected from the works of Marco Aurelio in other texts such as those by Pascal, specifically in Les Pensées (1947). Large parts of Barragán’s notes in this book are found in the section titled General Knowledge of Man. Barragán followed Pascal’s descriptions of the situation of uncertainty, estrangement, and anxiety that lead all human beings to the need to escape their reality through distractions (divertissements). In this regard, Barragán highlighted the following idea (Fig. 3, 4): “The one thing which consoles us for our miseries is diversion, yet this itself is the greatest of our miseries. For this it is which mainly hinders us from thinking of [40] ourselves, and which insensibly destroys us. Without this we should be weary, and weariness would drive us to seek a more abiding way out of it. But diversion beguiles us and leads us insensibly onward to death.”19 16 Cfr., Delgado, Joaquín, Pensamientos de Marco Aurelio, Manual de Epicteto y Cuadro de Cebes, Casa Editorial Garnier Hermanos, 1929, p. 64‐65. Ibidem, p. 277. Tr. by Benjamin Stewart. The Spanish text mentions the following: “XXXIV‐ Si la idea de algún placer te agrada, entonces, como siempre, ten mucho cuidado con ella, no sea que te arrastres por el mal camino. (…) Luego considera dos períodos diferentes: el tiempo que gozarás de ese placer, y el que después de haberte gozado, te arrepentirás y sufrirás remordimientos de él. Por el contrario, ve cuál será tu satisfacción, cuál estima tendrás por ti mismo si te abstienes de ese placer.ʺ 17 18 Barragán highlighted the following paragraph: ʺXII‐ How quickly everything disappears! Oh, man in the theatre of life and his memory over the passing of the centuries! In the same way, all the objects that distract our senses fade and, even more so those that fatten us on the pasture of pleasure. They terrorize us before the idea of pain or adulate our vanity. How frivolous, despicable, vile, corruptible and rotten does all of this seem to us in the light of reason!”. Ibídem, p. 23. Tr. by Benjamin Stewart. The Spanish text mentions the following: ʺXII‐ (…) ¡Ay! ¡el hombre en el teatro de la vida y su memoria en la sucesión de los siglos! Del mismo modo se desvanecen todos los objetos que distraen nuestros sentidos y más aun los que nos ceban con el pasto del placer, nos aterrorizan ante la idea del dolor o nos adulan nuestra vanidad.” Pascal, Blaise, Pensèes, Paris, La Bonne Compagnie, (introduction and notes de Geneviève Lewis), 1947, pp. 213‐214. The original text in French says the following: ʺLa seule chose qui nous console de nos misères est le divertissement, et cependant cʹest la plus grande de nos misères. Car 19 5 www.seipub.org/ijss International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 Source: Luis Barragán’s library in Casa‐Museo Luis Barragán in Mexico City. FIG. 3,4: BARRAGÁN’S UNDERLINE IN PAGE 213‐214 IN PASCAL, LES PENSÉES, 1947. In another section, Barragán highlighted the reasons for which human beings resort to distractions in order to avoid anxiety: “But upon stricter examination, when, having found the cause of all our ills, I have sought to discover the reason of it, I have found one which is paramount, the natural evil of our weak and mortal condition, so miserable that nothing can console us when we think of it attentively.”20 From Pascal’s perspective, human beings are in no condition to confront the vertigo of nothing if they do not renounce pleasure as a means of evading their own condition. This is why confronting the emptiness is what enables man to recognize his deeper needs. These ideas that Barragán underlined in his copy of Pascal’s Les Penseés are also linked to the content that he also highlighted in the text The Perennial Philosophy (1947) by Aldous Huxley. The large parts of the sections highlighted by Barragán in the pages of this book are found in the sixth chapter titled Mortification, Non‐Attachment, Right Livelihood. According to Huxley, to achieve a full life, it is necessary to separate oneself from avarice and self‐ interest, as well as from feeling, desiring and acting egocentrically. These mortifications are not themselves qualities of saintliness, rather the preparation for the beginning of a full life.21 Barragán coincided with Huxley in the idea of renouncing the passions as the beginning of the path to Supreme Wisdom. Thus: “(…) that mortification is the best which results in the elimination of self‐will, self‐interest, self‐centred thinking, wishing and imagining. (…) [T]he acceptance of what happens to us… in the course of daily living is likely to produce this result.”22 The process of renouncing is painful and, according to Huxley, entails the raising of consciousness, which enables man to embark on his own path toward spirituality. In this regard, Barragán highlighted the following: ʺThe righteous man can only escape suffering by accepting and going beyond it, and can only achieve this by passing from rectitude to total abnegation and a concentration in God.”23 Based on the doctrine of the English preacher William Law, Huxley argued that the spiritual life must occur in a cʹest cela qui nous empêche principalement de songer à nous, et qui nous fait perdre insensiblement. Sans cela, nous serions dans lʹennui, et cet ennui nous pousserait à chercher un moyen plus solide dʹen sortir. Mais le divertissement nous amuse, et nous fait arriver insensiblement à la mort. « Tr. in “The thoughts of Blaise Pascal”, translated from the Text of M. Auguste Molinier by C. Kegan Paul, London, Bell and Sons, 1901. [On line] Online Library of Liberty: a Collection of Scholary Works about Individual Liberty and free Markets (March, 2016) Available: http://oll.libertyfund.org/. 20 Ibídem, 1945, pp. 196‐197. The original text in French says the following: ʺMais quand jʹai pensé de plus près, et quʹaprès avoir trouvé la cause de tous nos malheureux, jʹai voulu en découvrir la raison, jʹai trouvé quʹil y en a une bien effective, qui consiste dans le malheur naturel de notre condition faible et mortelle, et si misérable, que rien ne peut nous consoler, lorsque nous y pensons de près. » Tr. in, ibid. 21 Cfr. Huxley, Aldous, Filosofía Perene, Buenos Aires, Editorial Sudamericana, (Tr. C.A. Jordana), 1947, p. 144. Ibidem, p. 149. The Spanish text mentions the following: ʺ(…) la mejor mortificación es la que conduce a la eliminación de la obstinación, el egoísmo y el pensar, desear e imaginar concentrados en uno mismo. (...) [L]a aceptación de lo que nos sucede (fuera, naturalmente, de nuestros propios pecados) en el curso del vivir cotidiano es probable que produzca este resultado.ʺ Tr. in, Huxley, Aldous, “The Perennial Philosophy”, London, Chatto & Windus, 1947, p. 118. 22 Ibidem, p. 330. The Spanish text mentions the following: ʺEl hombre recto sólo puede escapar al sufrimiento aceptándolo y pasando más allá; y sólo puede hacer esto pasando de la rectitud a una total abnegación y concentración en Dios.ʺ Tr. in, ibídem, p. 267. 23 6 International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 www.seipub.org/ijss climate of silence, and be isolated from all noise and distraction that impedes man from a finding an interior life for himself. Barragán highlighted the paragraph in which Huxley posited that the Twentieth Century is the Age of Noise. Technology and mass media such as the radio have transgressed silence. In many countries, broadcasting stations sell time to advertisers, generating a type of noise that enters via the human senses the regions of fantasy, knowledge, and sensitivity, until arriving at the deepest human desires. Noise entails the generation of desires and longings that impede the free and authentic clarification of that which the human being needs.24 Therefore, the art of advertising “is the principal cause of suffering and wrong‐doing and the greatest obstacle between the human soul and its divine Ground.ʺ25 Finally, The Unquiet Grave 1944 by Cyril Connolly was chosen for its condensed reflections and quotes on the human condition.26 In this text, Barragán underlined very similar ideas to those established by Huxley in relation to anxiety, spirituality and the living conditions of man in the Twentieth Century. From Connolly’s perspective, spiritual life is reached through the degree to which man’s physical satisfaction is intensified by nature. Nevertheless, the author considers it absurd that at the height of the Twentieth Century, we should return to a completely natural environment – to a desert island or to nudism. Thus, what Connolly proposes is to live according to nature, which implies living for the most part in the city, which, from his perspective, is where most subtle human climate is found. However, Connolly pointed out that human beings have erred in terms of the size of cities, in that the great metropolises slow spiritual development through two important factors – apathy and delirium. The first of these is born as a result of the mechanization of modern life, and the second emerges as a result of the violent methods used to escape or evade the great city.27 Therefore, more than evading the metropolis, 24 The paragraph highlighted and underlined by Barragán is the following: ʺThe 20th Century is, among other things, the Era of Noise. Physical noise, mental noise, and the noise of desire (...). And, it is not strange, in that all the resources of our almost miraculous technology has been launched in a general assault against silence. The most popular and influential of all the recent inventions, the radio, is not only a conduct through which flows into our homes a prefabricated racket. (...) It penetrates the mind and fills it with a Babel of distractions (...). There, as happens in many countries, the broadcasting stations support themselves through the sale of time to advertizers, with noise reaching all ears through the regions of fantasy, knowledge and feeling, up to the central nucleus of desires of self. Spoken or printed, and distributed across the ether or on wood pulp, all advertising literature has only one purpose: not to allow the will to achieve silence. The lack of desire is the condition for liberation and clarification. The condition for an expansive and technologically progressive system of mass production is a universal yearning.”Ibidem, p. 249‐250. The Spanish text mentions the following: ʺEl siglo XX es, entre otras cosas, la Época del Ruido. Ruido físico, ruido mental y ruido del deseo (...). Y no es extraño, pues todos los recursos de nuestra casi milagrosa tecnología han sido lanzados al general asalto contra el silencio. El más popular e influyente de todos los inventos recientes, la radio, no es sino un conducto por el cual afluye a nuestros hogares un estrépito prefabricado. (...) Se adentra en la mente y la llena de una Babel de distracciones (...). Y allí donde, como ocurre en muchos países, las estaciones emisoras se sostienen vendiendo tiempo a los anunciantes, el ruido es llevado a los oídos, a través de los regiones de la fantasía, el conocer y el sentir, hasta el núcleo central de los deseos del yo. Hablada o impresa, difundida por el éter o en pulpa de madera, toda la literatura de avisos tiene un solo propósito: no dejar que la voluntad logre nunca el silencio. La falta de deseos es la condición para la liberación y el esclarecimiento. La condición para un sistema expansivo y tecnológicamente progresivo de producción en masa es un anhelo universal. El arte de anunciar es la organización del esfuerzo por extender e intensificar lo anhelos ‐ esto es, extender e intensificar la operación de esa fuerza que (...) es la causa principal del sufrimiento y la maldad, y el mayor obstáculo entre el alma humana y su divina Base.” Op cit., Huxley, Aldous, Filosofía Perene, 1947, p. 308. 25 Ibid. This author was part of the generation of English writers that followed the Bloomsbury group, which emerged at the beginning of the Twentieth Century. Cfr. Connolly, C., Obra Selecta. Cyril Connolly, Barcelona, Editorial Lumen, (Tr. Miguel Aguilar, Mauricio Bach, y Jordi Fibla), 2005, p.19. 26 According to Connolly: “We progress through an intensifying of the power generated by the physical satisfaction of natural man whose two worst enemies are apathy and delirium; the apathy which spreads outward from the mechanical life, the delirium which results from the violent methods we use to escape. Happiness lies in the fulfilment of the spiritual through the body. Thus humanity has already evolved from an animal life to one more civilized. There can be no complete return to nature, to nudism or desert‐islandry: city life is the subtlest ingredient in the human climate. But we have gone wrong over the size of our cities and over the kind of like we lead in them; in the past the clods were peasants, now the brute mass of ignorance is urban. (…) To live according to nature we should pass a considerable time in cities for they are the glory of human nature, but they should never contain more than two hundred thousand inhabitants; it is our artificial enslavement to the large city, too sprawling to leave, too enormous for human dignity, which is responsible for half our sickness and misery.” Connolly, Cyril, The unquiet grave: a word cycle by Palinurus, revised edition with an introduction by Cyril Connolly, printed in Great Britain, [Kindle book version, 20 and 2nd paragraph after “The magic circle” title/Part I]. Available: https:www.amazon.com/ The Spanish text from Barragán’s volume mentions the following: “La felicidad humana yace en la realización del espíritu mediante el cuerpo. Así es como la humanidad ha evolucionado ya de la vida animal a una más civilizada. No puede haber un retorno absoluto a la naturaleza, al nudismo, a la isla desierta: la vida urbana es el ingrediente más sutil del clima humano. Pero nos hemos equivocado con respecto al tamaño de nuestras ciudades y al género de vida que en ellas llevamos; en el pasado, los zafios eran los campesinos; hoy, la masa bruta de la ignorancia es ciudadana. (…) Para vivir de acuerdo con la naturaleza tendríamos que pasar buena parte de nuestro tiempo en las ciudades, que son realmente la gloria de la especie humana, pero que no 27 7 www.seipub.org/ijss International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 Barragán highlighted and underlined the idea that spiritual life begins when human beings seek out creative work, communion with nature, and helping one’s neighbor. Barragán also focused his attention on the paragraphs where Connolly reflected on the decadence of the myth of the vocation of the artist in the Twentieth Century. According to the author, modern society, science and cultural products such as those produced by Disney have honeyed the original aspirations of art. Barragán underlined the following: “The artist, like the mystic, naturalist, mathematician or ‘leader’, makes his contribution out of his solitude (...) Art which is directly produced for the Community can never have the same withdrawn quality as that which is made out of an artist’s solitude. For this possesses the integrity and bleak exhilaration that are to be gained only from the absence of an audience and from communion with the primal sources of unconscious life. One cannot serve both beauty and power: ‘Le pouvoir est essentiellment stupide [Power is essentially stupid]’. A public figure can never be an artist and no artist should ever become one (...).ʺ28 Thus, returning to the manner in which Huxley equated the Twentieth Century as the Age of Noise, the problem established by Connolly in relation to the public figure29 and his tendency to evade his anxiety through the vices of work and pleasure can now be understood. In light of this situation, Connolly set out a path toward transcending the anxiety of the public figure. Barragán underlined the following (Fig. 5): “Reality is what remains when these pleasures, together with hope for the future, regret for for the past, vanity for the present, and all that composes the aroma of the self are pumped out of the air‐bubble in which I shelter. When we have ceased to love the stench of the human animal, either in others or in ourselves, then are we condemned to misery, and clear thinking can begin.”30 Source: Luis Barragán’s library in Casa‐Museo Luis Barragán in Mexico City. FIG. 5: BARRAGÁN’S UNDERLINE IN PAGE 129 IN CYRIL CONNOLLY, THE UNQUIET GRAVE, 1944. Anxiety is a condition indispensable to raising the consciousness of man. Furthermore, Barragán underlined what Connolly said of Heidegger: “The only reality is ʺanxietyʺ in the whole chain of beings. To the man lost in the world and its diversions this anxiety is a brief, fleeting fear. But if that fear becomes conscious of itself, it becomes anguish, the perpetual climate of the lucid man ʺin whom existence is deberían pasar de doscientos mil habitantes. Nuestro esclavizamiento artificial a la gran ciudad, demasiado dilatada para poder abandonarla, demasiado enorme para la dignidad humana, es el responsable de la mitad de nuestras miserias y dolencias.” Connolly, Cyril, La tumba sin sosiego, Buenos Aires, Editorial Sur, 1949, pp. 56‐57. Tr. in, ibidem, [3rd paragraph, second line after “Masterplay” title/Part II]. The Spanish text mentions the following: ”El artista, como el místico, el naturalista, el matemático o el caudillo, contribuye con su soledad. (…) El arte directamente producido para la comunidad jamás podrá tener la misma calidad retraída que el que brota de la soledad del artista. Pues éste posee la integridad y el júbilo interior que sólo pueden dar la ausencia de un público y la comunión con las fuentes prístinas de la vida inconsciente. No se puede servir a la vez a la belleza y a la fuerza: El poder es esencialmente estúpido. Un hombre público no puede ser un artista, y ningún artista podrá ser un hombre público (...).ʺ Ibidem, pp. 85‐86. 28 29 The concepts written in cursive script are used to emphasize the words that Cyril Connolly himself used in his text. Tr. in, ibidem [22nd paragraph after “Part III: La clé des chants” title]. The Spanish text mentions the following: “La realidad es lo que queda cuando estos placeres, junto con la esperanza del futuro, la añoranza del pasado, la vanidad del presente y todo aquello que compone el aroma del ser es extraído de la burbuja de aire en que vivimos. Cuando ha dejado de gustarnos el hedor del animal humano, en nosotros mismos o en los demás, en ese momento nos vemos condenados al sufrimiento y comienza el pensar claro”. Ibidem, p.129. 30 8 International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 www.seipub.org/ijss concentrated.ʺ31 Conclusions At the same time that Barragán recreated, in the photographs of the gardens at El Pedregal, environments inspired by the metaphysical aesthetic of De Chirico, the Mexican architect also recreated an inhabitant in constant reflection on the human condition. Behind the concept of the private garden that he explained in his discourse on the gardens at El Pedregal, Barragán proposed an environment of solitude in which modern man is able to lighten his existential load through a kind of rest that will allow him to meditate and aspire to creative and spiritual ideas. Barragán began his discourse indicating the habits that characterize the public figure. Given the condition of anxiety in which all inhabitants of the great metropolises live, modernity has provided the elements necessary to evade this condition through distractions or diversions. Barragán linked this way of evading the human condition to the way of life of the public figure, which is to say, those social personalities evade their condition through the measure in which they are able to lose themselves in the noisy climate of mass media and consumption. In light of this concern, the Mexican architect proposed private gardens in which an ideal environment of solitude could be recreated where the modern man could develop creative and spiritual ideas in his imagination. In the same way that Chirico represented ascetic environments in his paintings, Barragán proposed private gardens in which human beings could confront their condition in a meditative environment in order to achieve spiritual and physical rest. In this way, the link between the ascetic aesthetic of Chirico and Barragán’s reflection regarding with human condition can be seen in the following idea that Barragan underlined in Connolly’s book: “The masterpieces appropriate to our time are in the style of the early Chirico, (…) somber, magnificent yet personal statements of our tragedy; work of strong and noble architecture austerely coloured by loneliness and despair.”32 Independently of Barragán’s ambitions to recreate landscaped areas for the purposes outlined above, the ideological content on which the landscape design of El Pedregal was based, valid and transcendental. Barragán’s landscape proposal was strengthened by a profound reflection on the human condition which could be seen in the Mexican architect’s preoccupation with bringing a counterweight from his discipline to humanize the inevitable process of modernization underway in both Mexico and the rest of the world. REFERENCES [1] Connolly, C., Obra Selecta. Cyril Connolly, Barcelona, Editorial Lumen, (Tr. Miguel Aguilar, Mauricio Bach, y Jordi Fibla), 2005, 1016p. [2] Eggener, Keith, Gardens of El Pedregal, New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 2000, 162p. [3] ‐Fernández, Justino, Textos de Orozco (Textson Orozco), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (National Autonomous University of Mexico), General Office for Publications., 1983, 183p. [4] Noelle, Louise, Luis Barragán, búsqueda y creatividad, Colección de Arte no. 49, Primera Edición, México D.F., Dirección General de Publicaciones de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, C.U., 1996, 267p. [5] ‐Palomar,Verea Juán, Andrés Casillas de Alba, monografías de arquitectos del siglo XX, no. 7, Secretaría de Cultura del Gobierno de Jalisco, Guadalajara, México, 2006, 119p. [6] ‐Romanell, Patrick, The making of the Mexican mind, a study in recent Mexican thought, Lincoln, Nebraska, E.U., University of Nebraska Press, 1952, 213p. [7] ‐Riggen, Antonio, (ed.), Luis Barragán, escritos y conversaciones, Colección Biblioteca de Arquitectura no. 9, El Escorial, El Croquis Editorial, 2000, 200p. [8] ‐Zanco, Federica, Luis Barragán: La Revolución Callada, Barcelona, Barragán Foundation‐Vitra Design Museum, Ediciones Gustavo Gili, S.A., 2001, 319p. Tr. by Benjamin Stewart. The Spanish text mentions the following: “La realidad es la sola preocupación (Sorge) en la escala entera de los seres. Para el hombre perdido en el mundo y sus diversiones, esa preocupación es un temor breve y fugitivo. Pero si ese temor cobra conciencia de sí mismo se convierte en angustia (Angst), clima perenne del hombre lúcido, en el que vuelve a encontrarse la existencia.” Ibid. 32Tr. in, idem, [7th paragraph after “Masterplay” title/Part III]. The Spanish text mentions the following: “Las obras maestras apropiadas a nuestro tiempo son del estilo de los primeros Chiricos, (…); manifestaciones sombrías, magníficas, y no obstante personales de nuestra tragedia; obras de una robusta y noble arquitectura austeramente coloreadas por la soledad y la desesperación.” Idem, p. 139. 31 9 www.seipub.org/ijss International Journal of Sociology Study, Volume 4, 2016 Luis Barragán’s Library References ‐Barragán, Luis, “The Gardens for Environment: Jardines de El Pedregal lecture”. The Journal of the American Institute of Architects, vol. 17, no.4, April, (1952), 167‐5. ‐ Connolly, Cyril, La tumba sin sosiego, Buenos Aires, Editorial Sur, 1949, 208p. ‐ Delgado, Joaquín, Pensamientos de Marco Aurelio, Manual de Epicteto y Cuadro de Cebes, Casa Editorial Garnier Hermanos, 1929, 333p. ‐Huxley, Aldous, Filosofía Perene, Buenos Aires, Editorial Sudamericana, (Tr. C.A. Jordana), 1947, 427p. ‐Pascal, Blaise, Pensèes, Paris, La Bonne Compagnie, (introduction and notes de Geneviève Lewis), 1947, 588p. ‐Sanson, R.P, La souffrance et nous, Paris, Flammarion, 1933, 228p. Fernando Curiel Gámez Mexico City, 09/23/1976. Author’s Educational Background ‐Architecture Degree: Universidad de las Américas Puebla, A.C., Cholula, Puebla, México, 2001. ‐Arts and Aesthetics Master Degree: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Puebla, Puebla, México, 2005. ‐Architecture Design Master Degree: Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra, Spain, 2007. ‐Phd in Architecture: Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra, Spain, 2012. He is a Mexican architect who graduated from his first Masters degree in Arts and Aesthetics at the Universidad Autónoma de Puebla in 2005, with a dissertation on Daniel Libeskind’s architectural work that focused on the multidisciplinary approach (philosophy, literature, music and film) used in his design process. Years later, Fernando Curiel began his second Masters degree in Architectural Design at Universidad de Navarra, where he met such talented architects, historians and critics as Gonçalo Byrne, Henri Ciriani, Jose Antonio Martínez Lapeña, Francisco Mangado, Kenneth Frampton, Wilfred Wang, Francisco Liernur, Mark Cousins, Juan José Lahuerta and Marco Mulazzani. As soon as he concluded his courses and workshops, he began his PhD studies in architecture, theory and modern criticism at the same university. Given that he was always attracted to Luis Barragán’s architectural work, he decided to explore the philosophical ideas which led Barragán to create his own architecture. In 2007, Fernando returned to Mexico and began his research at Luis Barragán’s house‐studio in Mexico City. Analyzing his personal library, he was able to find some of the essential components of the ideas which supported Barragán’s architectural and landscaping work. In 2012, he presented his PhD dissertation, “Luis Barragán’s library: 1925‐1980”, and, a few months later, began working as a teacher at the School of Architecture at the Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey in Puebla. In 2013, Fernando was invited to give a lecture about “Luis Barragán’s cultural influences” at the Tecnológico de Monterrey Museum. The same year, he began working at the ITESM Postgraduate School as a teacher on the “Master Degree in Architecture and New Urbanism”. During this period, he gave a lecture at the Cancún and Playa del Carmen Society of Architects (Colegio de Arquitectos de Cancún y Playa del Carmen). These lectures were recently transformed into an article, “Fronteras Difusas: arquitectura, ciudad, arte y paisaje” (“Difuse Frontiers architecture, city, art and landscape”), which was published in Sinápsis Social Revista Científica de Sostenibilidad, v.1, no.1, April‐September 2014. In 2015, Fernando worked on an article entitled “Architectures without architects: Luis Barragán’s gaze through North African and Middle‐East architectures” (“Arquitecturas sin arquitectos”: La Mirada de Luis Barragán por las arquitecturas del Norte de África y Medio Oriente), which has already been accepted by the “Architecture, City, and Environment Magazine” at the Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña (Spain). Later, he gave a lecture entitled “Luis Barragán’s philosophical working itinerary between 40’s and 50’s” at the “Philosophy & Architecture International Postgraduate Conference” at the Center of Philosophy of the University of Lisbon. Dr. Curiel’s research interests are critical theory in architecture in Mexico and interdisciplinary design processes in culture and architecture. As a teacher at the School of Architecture at the Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey in Puebla, he is currently defining a research line on architecture and philosophy. 10