- Ninguna Categoria

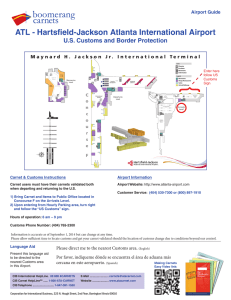

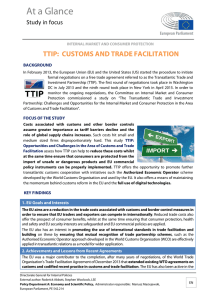

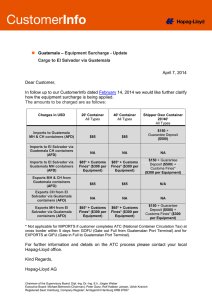

Customs issues falling under INTA`s new remit

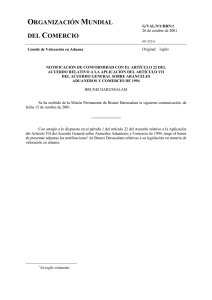

Anuncio