Racial Landscaping of the Frontier

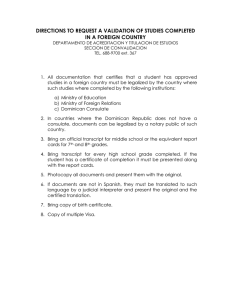

Anuncio