National Identity and Narrative Voice in Mexican Short Stories

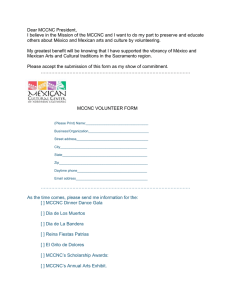

Anuncio

NARRATIVE VOICES AS REFLECTIONS OF THE DYSTOPIAN CITY IN UNA CIUDAD MEJOR QUE ÉSTA VIOLA MIGLIO University of California, Santa Barbara The present paper analyzes the short stories of the collection Una ciudad mejor que ésta (‘a city better than this one’) edited in 1999 by David Miklos, to discover the tension between the narrating voice and the main character(s) in the story.1 This anthology of young Mexican authors is peculiar in that the editor solicited the submission of short stories with the specific request that they should not write about Mexico City, but some other city. The result is a striking collection of stories taking place in many cities, often very far away from the Mexican capital, but at times simply within or below Mexico City. Some of the short stories in the collection portray the city)whichever this may be)as a sort of dystopian reality juxtaposed to a utopian entity (the unreachable El Paso in Parra’s story, or the obsessively tidy artist’s studio in García Bergua’s story), where the individual can still control his/her own destiny. In an effort to raise their stories beyond the parochialism of a local setting, and responding thus to the editor’s request, the language of the stories aims at being 1 I would like to thank Sara Poot-Herrera who first brought to my attention the use of language in M iklos’s collection and gave me the idea to write a paper on this topic. 966 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO ‘neutral’, ‘non-placeable’)paradoxically, however, the nonplaceability of the narration’s idiom becomes entangled with the dystopian image of the city in which the characters find themselves trapped, whereas the Mexican ‘slip-ups’ of the narrator or the openly Mexican idiomatic expressions of the characters seem to represent)if not utopia)at least the comfort zone, a subconscious and subversive declaration of identity that is even beyond the author’s control. The stories have in common that the characters are expatriates of some sort who look at and analyse the ‘alternative’ city where they are located through their Mexican eyes. In this case it is understandable that Mexican idioms and idiosyncrasies surface in their parlance. This is the case in Parra’s short story (Parra 1999), where his Northern Mexican character is almost “nailed” to the Mexican side of the Rio Bravo by his use of language, which is even excessively loaded with low class idioms, while his eyes soar over the tall buildings to his impossible dream city El Paso, so close and yet so far away. Even more interesting are cases where only the idiomatic expression of the characters or the narrator betray the identity of the city: this is the case of Ana García Bergua’s “La ciudad a oscuras”, where free indirect speech blending into stream of consciousness erases the borders between narrator and character, but both narrator and character are undoubtedly Mexican (el súper, mira nada más, su cuarto, una caguama, los niños héroes are just a few examples of linguistic and cultural mexicanismos). The cities they move in are the very imperfect Mexican capital and the perfect version of it reflected in the main character’s room-sized city of paint cans and paintbrushes, kept spotlessly clean and tidy in the artist’s effort to fight against the difficulties of living in the monstrously dirty, chaotic, and polluted city. Finally there are cases where there is a clear tension between the narrating voice and the character, this is the case VIOLA MIGLIO / CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD 967 in Montiel Figueiras’s “Metro”, where the narrator’s Spanish aims at being neutral, highly literary and non-placeable: ... el olfato zaherido por ese violento almizcle del que se han apropiado las habitaciones furtivas del orbe, un cigarrillo deshilachándosele en la comisura de la boca ... (147)2 whereas the characters’ Spanish is clearly Mexican: El teléfono volvió a crepitar. )¿Bueno? ... (144) In this case the city in question could be one of a few big Mexican cities with an underground train system as the title implies; the reader’s curiosity is undoubtedly awakened about the identity of the city; and once again in the different authors of the collection, one finds the neutral Spanish of the narrator pitted against the clearly regional, idiomatic Spanish of the characters, creating a tension that goes beyond the reader’s simple curiosity for discovering the identity of the city. The apotheosis of this tension is to be found in the short story opening the anthology, Jorge Volpi’s “Lo que Natura no da...”, where the author has clearly tried to separate the identity of the third person narrator from the main character, a Mexican young man studying at a university in Spain. Whereas the main character even openly plays on differences between peninsular Spanish and his own Mexican Spanish (see below), the narrator is excessively and unnaturally peninsular. This artificially sounding parlance is almost jarring for the reader, especially the careful one that will discover lexical marks of Mexican Spanish even where the author consciously tries to expunge any and every trace of local idioms. 2 For quotations from the primary texts, I will dispense with the year and only mention the page number. 968 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO I will analyse some of the short stories and show the mixture of regional idioms in the author’s attempt at attaining regional neutrality . LEAVING IT ALL BEHIND The opening verses chosen by Miklos to set the pace for the short stories collected in the book also provide the title for the whole anthology: Iré a otro país, veré otras playas; / I’ll go to another country, go to another shore, buscaré una ciudad mejor que ésta. / find another city better than this one. They are taken from the poem ‘The City’ by the important Greek poet Constantin Cavafy.3 Their tone is upbeat, full of enthusiasm and hope that the narrating ‘I’ of the poem will be able to leave a place which is not ideal (for what reasons the reader cannot know from the fragment), live new and seemingly positive experiences (I will go to another country, I will see different beaches) and find another city where life will be better. Already in Miklos’s choice of this poem we find that peculiar version of dystopia that conceives of the present situation of the character (the city of Cavafy’s poem and that of many of Miklos’s stories) as the “worst of all possible worlds” (Gottlieb 2001:3), juxtaposed to the possibility of redemption offered by the utopian pursuit of “another city”, a city better than this one. However, a twofold deception of the reader is concealed in the two)incomplete)verses quoted by Miklos. First of all, the narrating ‘I’ is not alone in the poem, the complete first line reads as follows: 3 See under Cavafy 2002 for the English version of the poem and Cavafis 1911 for the Spanish one. VIOLA MIGLIO / CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD 969 You said: “I'll go to another country, go to another shore, find another city better than this one.” (Cavafy 2002) Therefore there is a narrating voice different from the speaking ‘I’ of the direct speech, whose importance will become clear shortly. Also, the follow up to the quoted two lines is far from upbeat and optimistic: Whatever I try to do is fated to turn out wrong and my heart lies buried like something dead. How long can I let my mind moulder in this place? Wherever I turn, wherever I look, I see the black ruins of my life, here, where I’ve spent so many years, wasted them, destroyed [them totally. (Cavafy 2002) These lines set the tone for the second stanza, where the importance of the first narrator, the one saying ‘You said’ in line one, becomes as clear as his dooming voice: You won’t find a new country, won't find another shore. This city will always pursue you. You'll walk the same streets, grow old in the same neighborhoods, turn gray in these same [houses. You’ll always end up in this city. Don't hope for things [elsewhere: There’s no ship for you, there’s no road. Now that you've wasted your life here, in this small [corner, You’ve destroyed it everywhere in the world. (ibid.) Apart from being perversely deceptive as a choice of introducing verses)especially after the mutilation of the first part of the line and the reduction of the first stanza to the first 970 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO two lines, Miklos’s choice is exquisitely appropriate to the task at hand. He has asked the young participating authors to write about another city, anything but Mexico City, and they undertake the task full of hope and optimism, but little do they know that they are doomed to fail, that Mexico City will always loom large in the background of their narrative, even when their story takes place thousands of miles away or many centuries before Mexico City even existed. Unlike the novels that Gottlieb analyses, here we are not dealing with “societies in the throes of a collective nightmare” (2001:11), in Cavafy’s poem and in Miklos’s stories, the nightmare is lived by the individual, but there is still a sense that the character is a victim, experiencing a sense of displacement (typical of nightmares, as Gottlieb observes, but also of expatriate literature), and trying in vain to regain control over his/her destiny against superhuman forces that the character often does not comprehend. In Cavafy’s poem, these forces seems to be a sense destiny beyond human control and of guilt caused by the consciousness that the ‘I’ is the cause of his own ruin. In some of Miklos’s stories these incomprehensible forces are represented by the gray, faceless, post-industrial, sprawling city gobbling up its inhabitants. Why would Miklos be so perverse as to dupe the reader into believing that Cavafy’s poem offers any hope of redemption? One can only surmise that Miklos’s interpretation of the collection is in a way similar to the one presented here, i.e. that there is no escaping the looming city, and its dystopian ways, no matter how hard one tries, and that Cavafy’s verses and the title were chosen after the short stories were collected. And yet Miklos maintains that: [...] me llamó la atención una característica compartida por todos estos narradores: la ausencia de crítica política, social o económica patente en sus relatos. De igual manera, se evita casi VIOLA MIGLIO / CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD 971 toda referencia a lo “mexicano”. [...] Todo pareciera indicar que no pretenden heredar la tradición de sus antecesores inmediatos. (Miklos 1999:14) Miklos seems to be contradicting the clever choice of Cavafy’s poem, or at least he does not take it to its extreme conclusions, which is why he may have only excerpted the beginning two lines. Leaving homeland issues and problems behind seems to be a common thread of the very recent short story writers from Mexico in general, as pointed out also by Poot-Herrera (2002:2). How can we see the dogged persecution of these authors by the infamous D.F.? Sometimes the texture of the story admits it openly, at other times we can surmise it in the linguistic subtext that cements the stories. Again, linguistic tension in the Spanish of the short stories builds a parallel with Cavafy’s tension between demotic and purist Greek, which, as Auden mentions (1961) is a very relevant part of all his poetry. Fuguet and Gómez, the editors of McOndo)another Latin American anthology of short stories, very poignantly warn that “Temerle a la cultura bastarda es negar nuestro propio mestizaje” (1996, quoted in Poot-Herrera 2002:6). Denying their origin seems to be exactly what many of Miklos’s authors are trying to do, often literally debasing the mestizo or indigenous component of the Mexican culture and population. For example, Jorge Volpi’s narrator makes a wry comment in “Lo que Natura no da”: among the negative things found in Spain, he mentions: Discriminación en razón del color de la piel: las españolas prefieren que los latinoamericanos sean más morenos. (44) This implies, of course, that the narrator who complains is one of those ‘whiter’ Mexicans (güeros) and that his lighter skin 972 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO colour is one of the reasons why he has not been too successful in seducing Spanish women. Another example of what seems to be mestizo self-hatred manifested in the contempt for the Indian, is to be found in what Miklos mildly terms ‘misanthropy’ (Miklos 2002:14), but should really be defined as vehement misogyny and racism. I am referring to Guillermo Fadanelli’s “3000 pesetas” (Fadanelli 1999). The narrator is a Mexican in Madrid talking about an old flame of his who is now also living in Madrid and with whom he has shared a noche brava of sex and violence in a squalid hotel room. He mentions that the reason for a Spaniard having fallen in love at first sight with the woman is simply related to her ability at performing fellatio and says: ...todos los que estuvimos alguna vez en la cama con Leticia sabíamos que su boca, cuando dejaba de interesarse en las palabras y se concentraba donde debía, no te dejaba otro camino que el enamoramiento. (67) But his contempt for this ingenuous nymphomaniac of Indian origin, a working class Mexican whose parents made enormous sacrifices to put her through school, surfaces time and again: Me gustaba verla fingir una cara de puta que no tenía, una cara que, además de lo obvio, estoy seguro, había terminado de convencer a su amante de traerla a Madrid, ponerle un apartamento y soportar durante varios meses sus desplantes de india cosmopolita. (67) And finally, as the narrator and main character decides to let her wait at the café without showing up: ...pensando en la mujer que me esperó tres horas antes de pagar la cuenta... e irse, muy segura de sí misma... a recorrer el mundo VIOLA MIGLIO / CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD 973 y a mostrarle a los europeos lo que es capaz de hacer una india que ha decidido superarse. (70) So not only are these young authors not interested in political or social engagement, but they create characters)and some of them are suspiciously reminiscent of the authors4)who are politically incorrect intellectual snobs, güeros that feel superior to their fellow-Mexicans both because of social status, education or skin colour. THE NARRATOR AND THE CHARACTER(S) Miklos makes a grouping of the authors taking part in the anthology: who develop an anecdote in present progressive narration (Bergua, Parra, Volpi), those who are fascinated by literary tradition and history and pay particular attention to language (Enrigue, García-Galiano, Granados, Herrasti, Soler Frost), those in between (González Suárez, Montiel Figueiras), and finally those describing the marginalization and excess of a parallel sub-world (Bellatín, Díaz Enciso, and Fadanelli). I would like to propose a different grouping, based on the identity and type of narrator: Author 1s t person narrator Volpi X Herrasti Fadanelli 4 Omniscient narrator Mexican narrator/ main character Mexican city? Mexican X X Other type )) Mexican In two stories, Volpi’s and Gonzáles Suárez’s, the main character is a Mexican who received a scholarship to study abroad, which they misuse doing anything but studying... Their bibliographical note mentions that the authors both received scholarships from the Mexican Writers’ Centre and one of them, Jorge Volpi, was at the time studying in Salamanca, just like his character in ‘Lo que Natura no da...’ 974 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO GarcíaGaliano GonzálezSuárez )) X X Mexican Soler Frost Omniscient blending into 1s t Foreign Bergua X Mexican Enrigue X )) Montiel Figuei. X Mexican Granados S. X Díaz Encisa Bellatin Parra X X Unclear X Foreigner )) X X Mexican X There is no real statistically significant tendency connecting Mexican character and type of narrator, but possibly four out of five first person narrators are Mexican. So that whenever the narrator is a character in the story, the tendency is for the narrator to be Mexican, whereas the more objective third person, often omniscient narrator is usually not connected to Mexico, linguistically or otherwise. In the next three sections I will analyse how the narrator’s use of language reveals a tension between regionalism and globalisation in two authors from Miklos’s anthology. I will not analyse stories that take place in Mexico, because in such stories Mexican idioms are only to be expected. I chose two stories that do not take place in Mexico: one of them has a Mexican narrator/main character (Volpi’s), the other one (Herrasti’s) does not. The analysis will show that there is a VIOLA MIGLIO / CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD 975 tension between what is said and how it is said, the modismos often denying the cosmopolitan desires of the author, doggedly pursuing the narrator to remind him that no matter how far away one flees, one’s nature will always be part of whom we are. LINGUISTIC TENSION IN VOLPI’S “LO QUE NATURA NO DA ...” Volpi’s “Lo que Natura no da” is a story about a Mexican student in Salamanca attending lectures given by a famous Basque professor, becoming infatuated with the professor’s wife, and being the complacent victim of the professor’s jealousy. Most of the dialogues are based on differences between peninsular and Mexican Spanish: –¿De dónde eres?)Me halagó su interés). ¿Colombiano? –Mexicano. –Mejicano )me arremedó con un acento calcado a Speedy González. (25) And also: Ya me disponía a comenzar mi conferencia sobre las particularidades lingüísticas del español de México (el único tema con que lograba atraerme un poco de atención) [...] (26) The peculiarity of the narrator is that he is a Mexican and, as mentioned before, he consciously plays on Mexican idioms and differences between peninsular and Mexican Spanish. Yet there are some linguistic characteristics of the text that aim at making it either linguistically neutral, or even peninsular. One particularly jarring feature is the repeated use of the past subjunctive in –se: of 29 instances in the text, only two are –ra forms, and 27 –se forms. Luego miró su reloj y, como si nada hubiese pasado, se limitó a añadir: –¿Nos vamos? (ibid.:28) 976 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO In Latin American Spanish, this form has basically disappeared apart from literary discourse, where it may still be found sparingly. In Spain it is also most often relegated to cultivated written Spanish. However, not even in Spain would the frequency of this type of form be so high in a text: it must be a conscious manipulation on the part of the author. The author is subtly trying to prove the intellectual superiority of his alter ego-narrator-main character, who suffers at the hands of his Spanish professor and wife. It is a type of grass roots revenge: the character openly criticises the idea of the supposed superiority of the Spaniards, but must often give in. These are examples of his criticism: Sólo un espíritu altivo e irónico como el suyo podría atreverse a iniciar la penúltima de sus conferencias [...] con estas palabras [...] Escandalizado, me volví para mirar al público, pero no pude ver más que sonrisas morosas y gestos de asentimiento [...] (17) Trastabilló un par de veces ... e incluso cometió una pifia al tratar de acordarse de una parte de la Iliada, en griego, y reconocer que había olvidado uno de los versos. (A pesar de la conmovida dispensa que le tributaron mis colegas, yo tenía la impresión de que ninguno notó la falla). (29-30) And this is the ironic but significant attitude of the character: Era una especialista en intimidarme. Con razón Moctezuma había sido vencido por Cortés: no era una cuestión de armas sino que de actitud. (31) And the idea of the Spanish conqueror and the Mexican conquered is taken up a few pages later: Me sentí como un imbécil. No debía permitir que ella dominase la situación; ella podía tener toda la sangre de conquistadora que quisiese, pero yo no iba a dejar el honor patrio por los suelos. (33) VIOLA MIGLIO / CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD 977 Therefore the character possesses the meta-linguistic abilities to discuss at length the differences between Mexican and peninsular Spanish, as well as openly criticising his colleagues and professors and thereby showing his intellectual superiority. The narrator, on the other hand, shows his superiority by his fluency in both varieties)and specifically in peninsular Spanish. Or at least this is what the author would like to show, and he does so by using)se past subjunctives, but also by other means: literary Spanish has adopted a trait that is originally typical of Galician and Galician authors writing in Spanish such as Álvaro Cunqueiro and others. It is the use of a –ra past subjunctive with the meaning of the past perfect (in the case below instead of ‘había reiniciado’): Desde que cuatro siglos atrás fray Luis de León reiniciara su curso en estas mismas aulas [...] luego de los años de injusto encierro que lo habían separado de sus queridas lecciones [...] (17) [my italics] As well as a number of lexical items often openly borrowed, but at times surreptitiously introduced: charla ‘lecture’ (19) instead of Mex. plática, resaca ‘hangover’ for cruda etc. But when it is least expected, the mexicanisms seep through: so that on page 21 one finds plática for charla ‘lecture’, graduarse ‘to graduate’ (30), and even a –ra past subjunctive right in the middle of an apology of the Mexican albur (35). Not to mention that he has his very Spanish character Felicidad use the verb escuchar ‘listen’ for oír ‘hear’ (40), again a very Mexican usage unknown in standard peninsular Spanish. The result is an unfortunate mixture not just of voluntary regionalisms, but also of subconscious ones that make the text very hybrid and prove once again Cavafy’s profecy that “This city will always pursue you.” 978 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO LINGUISTIC PERFECTION AND MEXICANISMS: VICENTE HERRASTI’S “APÓCRIFO TESALIO ” This short story would later become a novel, La muerte del filósofo (Herrasti 2004), that critics have abundantly praised for the refined use of language and the ability to recreate ‘the spiritual universe of the Greeks’ (Miguel León-Portilla quoted in Herrera 2005:1). The story takes place in ancient Greece, where Gorgias, the famous rhetorician, is writing his last speech in what is to be the night before his death. The musings of the old man5 and the thoughts of the tyrant Jason, who is his Maecenas, intertwine in this superbly constructed, complicated short story about personal events that affect not only the main characters (their death), but also the city and the people they have come in touch with. In this short story, diction is paramount and every word has been carefully weighed before being inserted in the text. Miklos has, quite appropriately, placed this author in the group of those who write little (a cuentagotas), and whose main preoccupation is the precision of language (Miklos 1999:13). Consider this passage: Le dolían los ojos y apenas soportaba los calambres que aquejaban las articulaciones de su mano diestra (la siniestra ya de plano estaba inmóvil, pues el meñique se había torcido tanto que desde hace décadas reposaba sobre la primera falange del dedo medio). (49) Not only is there a desire to find the mot juste at all times, but also a strain to find the archaic word (flama for llama, siniestra for izquierda, hinojos for rodillas are just a few examples). 5 In the short story he dies at 109, the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy says 105, 483-378 BCE. (http:// www.iep.utm.edu/ g /gorgias.htm, accessed 12/5/05). VIOLA MIGLIO / CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD 979 Here, and more often than in Volpi’s story, the past subjunctive substitutes the past perfect: [...] vociferó el cetrero analizando ahora las entrañas de la oca que antes persiguiera Gorgias. (61) [my italics] Gorgias se limitó alternativamente a mirar el rostro del tirano y los rollos iluminados por las velas que éste trajera. (62) [my italics] In this case it may be ascribed to the desire of the author to make his text supra-national, adopting thus peninsular traits that have become recognizably literary usage. Another one of such traits is leísmo, i.e. the use of the indirect object pronoun for the direct object, when the referent is a human male: Jasón debía su intempestiva vigilia al cetrero que recién le había visitado en sueños. (53) The narrator is an omniscient third person, and given the setting, no Mexican characters are to be found. Herrasti is a self-defined ‘obsessive compulsive writer because I take great care about correct language use’ (Herrasti interviewed in Herrera 2005:1). Despite the painstaking attention to detail, the omniscient narrator who even penetrates dreams shows some peculiar characteristics that localize him (it?) very solidly in Mexico. Let’s examine them: one may perhaps doubt the use of de plano meaning ‘completely’ as deriving from a more frequent Mexican usage of this adverbial form, but the use of escuchar ‘listen’ for oír ‘hear’ is undoubtedly a mexicanism: “Qué pena que con el hombre muera la palabra”, dijo Jasón por lo bajo, aunque no lo suficiente para evitar que Gorgias escuchara. [...] “Maestro, ¿puede escucharme?” (59) 980 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO Another lexical hint to the origin of the text is the use of the word necio for ‘stubborn’: the first and most common meaning of this word in Spain is ‘ignorant’ according to the R.A.E., but that cannot be the meaning in this case, as Gorgias is talking here about Plato: “Quien se asocia con tiranos tarde o temprano es tiranizado”, bien claro se lo había dicho; mas Platón era joven, impetuoso y necio. (50) There are few certain examples of Mexican idioms in Herrasti’s text, unlike the jarring note that the mixture of regional registers causes in Volpi’s story, only a magnifying glass can reveal the slight linguistic discrepancies. What is peculiar is the desire of the author to make his text supraregional, stamping out Mexican idioms by using many more clearly recognizable peninsular ones. Even in what is an undeniably finely chiselled construction, repressing Mexican parlance is not always completely possible. CONCLUSION We agree with Sara Poot-Herrera (2002:454), who uses the word liminal about the young generations of Mexican short story writers, an epithet that originates with Mauricio Carrera (Riverón and Carrera 2002). He talks in fact about a ‘Liminal Generation’ (Generación del Umbral), that is, a generation of changes and transitions that grew up during decades of economic crisis, which maybe explains why they refuse to write about Mexico, a country marked by frustration and disappointment (Carrera quoted in Poot-Herrera 2002:454). This refusal means turning their back on Mexico and looking for a global context. While the use of standard Spanish is an open attempt at reaching for this global context and it is perhaps important in order not to alienate readers from different regions, it is not always possible to expunge all regionalisms. Depriving the VIOLA MIGLIO / CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD 981 text of the author’s Lokalkolorit can be equated to the objectionable practice of some translators that decide to expunge all local references to the place where the original story takes place in order to make it more appealing to the public that reads the translated text. Such adaptations make the original much less incisive and are ultimately futile, since they fail to make the reader of the translation approach a new and unknown world. I hope to have shown that no matter how neutral authors try to be, some mexicanisms are bound to surface in a longer text. While I will not attempt at broaching the subject of ‘which standard Spanish’ should be used by Mexican writers,6 I would like to point to the tendency that these young writers from Mexico have of equating standard Spanish or neutral Spanish with peninsular Spanish. This is a dangerous misconception: peninsular Spanish is not any more neutral than any other standard variety: forcedly using peninsular idioms runs the risk of producing hybrid languages with a jarring result (as in Volpi’s short story). Moreover it has a problematic ideological side: these authors, so up in arms against Mexico and wanting to leave it all behind, in fact seem to resort to their old colonial masters for linguistic guidance. A perverse twist indeed, if one thinks in terms of postcolonial studies... Their attitude seems to reinforce Mexican malinchismo, excessive appreciation for the foreign and contempt for all things Mexican, the feeling of inferiority and self-betrayal Mexico harbours towards the ‘colonial powers’ (Spain first and later the U.S.A.), embodied by Cortés’s lover Malinche. Even if this were true, the subconscious pointers subversively establish cultural identity revealing the Mexican origin of the text, and rebelling against the author’s levelling hand. 6 Or Latin American ones in general, see the detailed discussion of this topic in Thorgrímsdóttir 1999. 982 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO Clearly, the tension between the narrative voice and the setting or the characters reflects a discomfort of the author with his/her surroundings; perhaps the desire for ‘neutral Spanish’ is an attempt, not only at leaving Mexico and its problems behind, but also at reaching a wider audience, or at being considered global, international writers, rather than merely parochial, Mexican ones. At the same time, the impersonality of the narrating voice reflects the dehumanized, dystopian nature of the big city)a modernist motif, see for instance D. H. Lawrence)from which any escape fails. In this sense, neutral Spanish is also an attempt to control and contain the city, denying its fragmentation and complexity. However, just as the sprawling, grayness, inhumanity and chaos of the big city are unstoppable)language variation is equally irreducible. VIOLA MIGLIO / CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD 983 WORKS CITED AUDEN , W. H. 1961. “Introduction to Cavafy’s poems.” In The Complete Poems of Cavafy. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc. CAVAFIS , C. 1911. ‘La ciudad.’ http:// www. architecthum. edu. mx/ Architecthumtemp/ poemario/cavafis/1ciudad.htm (accessed 11/28/2005) ))))). 2002 (1911). “The City”. Translated by Edmund Keeley & Philip Sherrard http:// plagiarist.com/ poetry/ 2260/. (accessed 11/28/2005) FADANELLI, G. 1999. “3000 pesetas”. In Miklos (ed.) 1999: 65-70. GARCÍA BERGUA , A. 1999. “La ciudad a oscuras”. In Miklos (ed.) 1999: 117-126. GARCÍA -GALIANO , J. 1999. “Grenzgänger”. In Miklos (ed.) 1999: 71-84. GOTTLIEB , E. 2001. Dystopian Fiction East and West: Universe of Terror and Trial. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. MONTIEL FIGUEIRAS, M. 1999. “Metro”. In Miklos (ed.) 1999: 139158. FUGUET , A. and S. GÓMEZ . 1996. “Presentación del país McOndo”. In McOndo. Barcelona: Grijalbo/Mondadori. ))))) (eds.). 1996. McOndo. Barcelona: Grijalbo/ Mondadori. HERRERA , JORGE LUIS . 2005. “Entrevista con Vicente Herrasti”. (1-4) http:// sepiensa.org.mx/ contenidos/ 2005/l_herrasti/herrasti _ 1.htm (accessed 12/5/05) HERRASTI , V. 1999. “Apócrifo tesalio”. In Miklos (ed.) 1999: 4963. ))))). 2004. La muerte del filósofo. México: Joaquín Mortiz. MIKLOS , D. 1999. “Nota preliminar”, Introduction to Una ciudad mejor que ésta. México: Tusquets. 11-15. ))))). (ed.) 1999. Una ciudad mejor que ésta. México: Tusquets. PARRA , E. A. 1999. “El escaparate de los sueños”. In Miklos (ed.) 1999: 217-232. POOT -HERRERA , S. 2002. “El que se mueva no sale en la antología Varia cuentística mexicana: 1996-2000”. In S. Poot-Herrera et al. Cuento bueno hijo ajeno: la ficción en México. Tlaxcala: Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala. 984 CIEN AÑOS DE LEALTAD / VIOLA MIGLIO POOT -HERRERA , S. 2004. ‘El lector se acerca a su cuento: 20002003’. In M. Muñoz et al. Cuento muerto no anda: la ficción en México. Tlaxcala: Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala. RIVERÓN , R. and M. CARRERA (eds.). 2002. Cuentos sin visado. México: Lectorum. THURÍM UR BJÖRG THORGRÍMSDÓTTIR . 1999. Dos normas lingüísticas coexistentes en el español de Costa Rica. Unpublished B.A. Thesis: University of Iceland. VOLPI, J. 1999. “Lo que Natura no da...” In Miklos (ed.) 1999: 1748.