PDV 70 GB ESP.indd

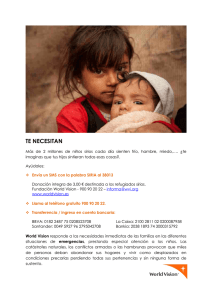

Anuncio