Alta presión isostática: estudio del color

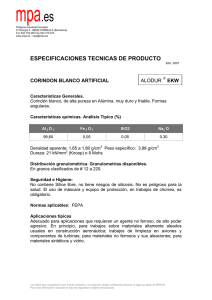

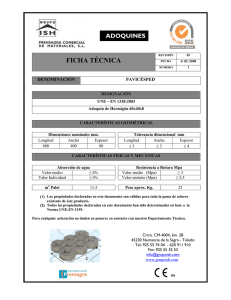

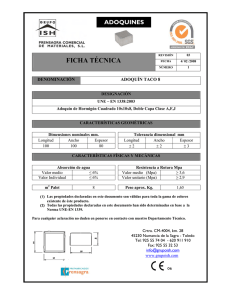

Anuncio