Openness and Geographic Neutrality. How Do

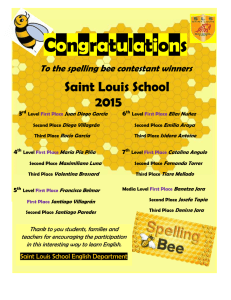

Anuncio