Biotecnología - VI Congreso Internacional

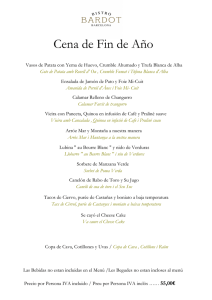

Anuncio