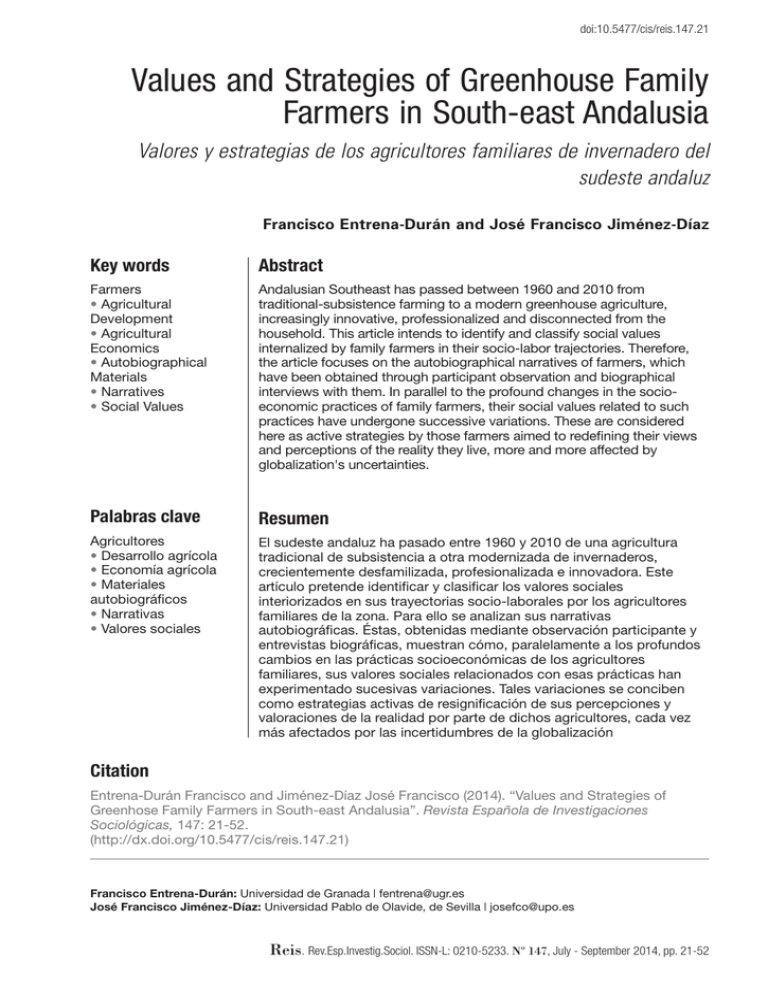

Values and Strategies of Greenhouse Family Farmers in South

Anuncio