Article - University at Albany

Anuncio

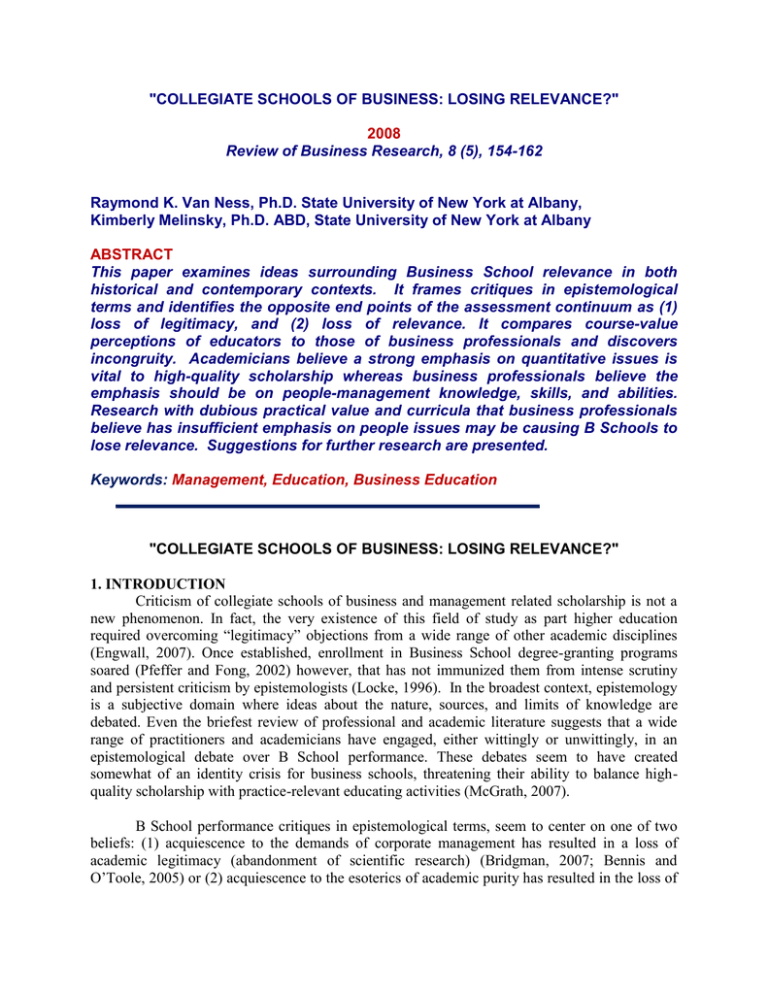

"COLLEGIATE SCHOOLS OF BUSINESS: LOSING RELEVANCE?" 2008 Review of Business Research, 8 (5), 154-162 Raymond K. Van Ness, Ph.D. State University of New York at Albany, Kimberly Melinsky, Ph.D. ABD, State University of New York at Albany ABSTRACT This paper examines ideas surrounding Business School relevance in both historical and contemporary contexts. It frames critiques in epistemological terms and identifies the opposite end points of the assessment continuum as (1) loss of legitimacy, and (2) loss of relevance. It compares course-value perceptions of educators to those of business professionals and discovers incongruity. Academicians believe a strong emphasis on quantitative issues is vital to high-quality scholarship whereas business professionals believe the emphasis should be on people-management knowledge, skills, and abilities. Research with dubious practical value and curricula that business professionals believe has insufficient emphasis on people issues may be causing B Schools to lose relevance. Suggestions for further research are presented. Keywords: Management, Education, Business Education "COLLEGIATE SCHOOLS OF BUSINESS: LOSING RELEVANCE?" 1. INTRODUCTION Criticism of collegiate schools of business and management related scholarship is not a new phenomenon. In fact, the very existence of this field of study as part higher education required overcoming “legitimacy” objections from a wide range of other academic disciplines (Engwall, 2007). Once established, enrollment in Business School degree-granting programs soared (Pfeffer and Fong, 2002) however, that has not immunized them from intense scrutiny and persistent criticism by epistemologists (Locke, 1996). In the broadest context, epistemology is a subjective domain where ideas about the nature, sources, and limits of knowledge are debated. Even the briefest review of professional and academic literature suggests that a wide range of practitioners and academicians have engaged, either wittingly or unwittingly, in an epistemological debate over B School performance. These debates seem to have created somewhat of an identity crisis for business schools, threatening their ability to balance highquality scholarship with practice-relevant educating activities (McGrath, 2007). B School performance critiques in epistemological terms, seem to center on one of two beliefs: (1) acquiescence to the demands of corporate management has resulted in a loss of academic legitimacy (abandonment of scientific research) (Bridgman, 2007; Bennis and O‟Toole, 2005) or (2) acquiescence to the esoterics of academic purity has resulted in the loss of relevance (abandonment of practical research) (Augier and March, 2007). Since academic research is a fundamental element in curriculum development, criticism of one is criticism of both. B School relevance is dependent upon both practical research and classroom activities that address contemporary problems. 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Practical Research Alarmingly, the apparent preoccupation with how they are perceived by other academic disciplines rather than how they influence business practice does not bode well for B School relevance (Watson, 1993). Business schools may be well advised to take a page from natural science researchers who have disregarded epistemological critiques and continued their work on the basis of practicality (Locke, 1996). The consequence of surfeit concentration on “knowledge purely for its own sake” may be a popular concept for academic purists but for pragmatists it is the short path to irrelevance. Achieving and sustaining practical relevance requires the integration of practitioner concerns, challenges, and problems to the management research process (Augier, 2006). Unfortunately, some analysts believe that B Schools have already drifted too far from this concept since there is little evidence to suggest that their research has any influence on management practice (Pfeffer and Fong, 2002). The value of research connected to business practice has long been considered an essential building block of relevant curricula. For example, in May of 1920, while addressing the Association of Collegiate Schools of Business, Horace Secrist of Northwestern University cautioned that although students need to be trained in the elements of scientific methods, they must also be acquainted with business problems in order to render service to business (Secrist, 1920). In July of 1931, a paper presented at the 13th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Business by G. A. Warfield, Dean of the School of Commerce, Accounts, and Finance at the University of Denver echoed the sentiments of Dr. Secrist. Maintaining channels of communication with business using surveys of former students such as those used by Wharton and the University of Pennsylvania provide meaningful data for guiding and strengthening research and the educational process (Warfield, 1931). 2.2 Training versus Educating Unfortunately, research associated with business practice is often viewed as being outside of the scientific model not only by other academic disciplines but also by B Schools themselves (Bennis and O‟Toole, 2005). Thus, practical research – business related – is frequently discouraged thereby enhancing perceptions by business professionals that B Schools are losing relevance (Debnath, Tandon, and Pointer, 2007). It is not impossible to wonder if the fear of being classified as a T School (Training) is an underpinning factor in the intense and frequently myopic focus on the scientific model to the exclusion of practical research. Concerns of this nature have been articulated in the literature for decades. For example, Lillian M. Gilbreth, in 1935, expressed frustration that other disciplines within colleges, including women‟s colleges, failed to recognize the educational values of business studies, viewing them as training activities rather than educational activities. Nevertheless, she believed that criticism by the “uninitiated” did not alter the reality that business education is undeniably important to society. In her opinion, the value of business education was dependent upon the ability of academicians to understand the history of business, comprehend the role of education, observe and understand the business climate, and have the courage to make and accept the required changes (Gilbreth, 1935). 2.3 Perceptions of Educators versus Business Professionals Making and accepting the changes necessary to ensure relevance in research and curricula can be a challenging endeavor. The process is likely exacerbated by epistemological critiques involving the suggestion that suggest B Schools run the risk of transforming themselves into T Schools as they acquiesce to the demands of practitioners. However, this line of criticism is misguided since training concentrates on refining skills for a specific task whereas educating is the process of broadening and enriching the whole person (Walker, Hanson, Nelson, and Fisher, 1998). In other words, training is a narrowly focused program that leads to high proficiency in a specific skill (Moore, 1998) while educating is the process of exchanging knowledge related to a broad range of concepts (Brotheridge and Long, 2007). Business professionals prefer graduates with an educational experience that is broad in scope and one that enables them to understand and communicate ideas on a wide range of issues (Bukics and Fleming, 1999; Lewis and Ducharme, 1990). Training activities are most effectively conducted within corporate settings or by large-scale personnel recruiters (Safon, 2007). Although educators and business professionals generally agree that B Schools are not and should not be T Schools they do have some epistemological disagreements related to the nature and limits of various topics within curricula (Levenburg, 1996). In business, it is understood that stagnation deteriorates relevance. Progress is impossible without change. Similarly, ensuring relevance in academic programs requires periodic restructuring (Klimoski, 2007; Learmonth, 2007; Schlesinger, 1996). Unfortunately, B Schools have a tendency to resist change, which may account for disagreements with business professionals as to the value of specific courses within curricula (Kleiman and Kass, 2007). For example, Quelch (2005) and Bennis and O‟Toole (2005) assert that educators tend to focus too much on the hard analytic skills and not the „softside‟ of management. We therefore propose the following hypotheses regarding the value business professionals and educators place on various content areas within business curriculum. Hypothesis 1: There is a significant difference between educators and business professionals in the perceived value of specific content areas within a business curriculum. Hypothesis 2: Professional designation (business professional versus educator) will have a significant effect on the placement of value of various content areas, such that educators will have a significantly higher mean score in analytical content areas than business professionals. 3. METHODS 3.1 Sample and Procedures Two samples were needed for this study. The first sample, business professionals, was selected at random from the Society of Human Resource Management database of companies throughout the United States. The organizations selected included a cross-section of industries, including manufacturing, professional services, retailing, financial services, health and human services, and information technology. Contact information was collected for individuals holding various positions within each organization. Participation in the survey was voluntary and it was administered by paper via U.S. mail. Anonymity was guaranteed by not including any identifying items on the questionnaire. The second sample of educators was drawn from a website published by the University of Texas, Austin that lists all regionally accredited college level educational institutions in the Unites States. Two-year and four-year educational institutions were selected to participate in the survey. The surveys were directed to individuals identified as Deans, Associate Deans, or Chairs of Business Departments. The surveys were distributed to individuals in paper format through US Mail. Again, anonymity was guaranteed by not including any identifying items on the questionnaire. Of the combined 301 mailings, 108 responses were received, three of which were unusable. This left a total combined sample size of 105 (63 business and 42 educators) and a total usable response rate of 34.9%. Of the 63 business managers that responded, 22% were from manufacturing, 19% from professional services, 13% from retailing, 10% from financial services, 8% from health and human services, 5% from information technology, and 23% from other industries. The business sample had a gender distribution of 65% female and 35% male, with most respondents being between the age of 46 and 55. Of the 42 educators that responded, 36% were from two-year colleges and 64% were from four-year colleges. The educator‟s sample had a gender distribution of 38% female and 62% male, with most respondents being between the age of 46 and 55. 3.2 Measures (1) Perceived Value of Academic Content Areas. A measure was created to assess business and educational professional‟s perceived value of specific academic content areas. Interviews were held with various subject matter experts, including individuals from two-year and four-year academic institutions, business professionals from various industries and an officer of the Society of Human Resource Management. Based on these interviews, critical academic content areas were selected for a survey of educators and business professionals. Content areas included accounting, finance, economics, marketing, management, operations management, humanities/liberal arts, mathematical/analytical and foreign language fluency/international management. Each content area had specific courses listed within them. For example, management included courses such as organizational behavior, leadership and human resource management. Every individual was asked to rate the value of each course on a scale from one to five, one being unimportant to a business education and five being very important to a business education. (2) Professional Designation. The independent variable, professional designation, was measured through data collection. All surveys collected from business professionals were coded 1 and all surveys collected from educators were coded 2. (3)Demographic variables. Demographic variables, such as gender and age group were measured through two simple questions. Gender was simply measured by requesting individuals to denote either male or female on the survey. Females were coded 1 and males 2 for analysis. Age group was measured through a question requesting individuals to denote their age group. Age group classifications were “under 36”, “36-45”, “46-55”, “56-65”, and “65 & up”. Each age group was coded separately for analysis. 3.3 Analyses The means, standard deviations and two-tailed Pearson Correlations were calculated for the dimensions of academic curriculum. The results can be seen in Table 1. Multivariate analyses of variance were then performed to find the differences in the separate areas of academic curriculum as a function of professional designation (business professionals versus educators). The separate dimensions of academic curriculum were calculated using the mean dimension score for each individual participating in the survey. The Wilkes‟ Lambda was calculated, followed by the calculation of separate univariate F-tests and cell means in order to ascertain the impact of the main effect of professional designation on each academic content area. The results of these analyses can be found in Tables 2 and 3. 4. RESULTS As seen in Table 1, there were moderately strong correlations between many of the dimensions of academic curriculum. In general, courses that use analytical assessment, such as Accounting, Finance, Operations Management and Mathematical/ Analytical courses had significant positive Pearson correlations at the p < .01 level. Marketing and Foreign Language Fluency / International Management courses also had significant positive Pearson correlations at the p < .01 and p < .05 levels with each other and the analytical assessment courses above. In addition, management courses tended to have smaller insignificant correlations with the analytical assessment courses and significant relationships with Marketing and Operations Management courses. The significant correlations were to be expected due to the similar nature of the courses. TABLE 1 PEARSON CORRELATION MATRIX OF THE AREAS OF BUSINESS CURRICULUM 1. Accounting Courses 2. Finance Courses 3. Economics Courses 4. Marketing Courses 5. Management Courses 6. Operations Mngt Courses 7. Humanities Courses 8. Mathematical / Analytical Courses 9. Foreign Language Fluency / International Mngt Notes: N = 105; ** p < .01, * p < .05 (2-tailed) Mean 4.30 3.39 3.39 3.55 3.98 4.17 3.03 3.37 2.36 SD 0.73 0.89 0.90 0.84 0.63 0.58 0.76 0.79 0.87 1 0.47** 0.34** 0.24* 0.09 0.33** 0.22* 0.38** 0.16 2 0.38** 0.47** (0.02) 0.04 0.30** 0.25** 0.26** 3 4 0.19 (0.14) 0.26** 0.05 0.15 0.23* 0.21* 0.42** 0.06 0.26** 0.42** 5 6 0.38** 0.07 0.07 (0.07) 0.15 0.10 0.12 7 8 0.25** 0.18 0.31** 9 - The results for the multivariate analysis of variance on the effect of professional designation on the various areas of business curriculum can be seen in Tables 2 and 3. The Wilkes Lambda was moderate and significant, with business or educator identification providing for approximately 34% of variability in the selected course areas. The results of the univariate Ftests and the cell means provided a better understanding of the influence of the main effect of professional designation on the individual academic dimensions. As seen in Table 2, professional designation had a strong significant effect on Finance Courses and Economics Courses with p < .001. It also had a significant effect on Humanities / Liberal Arts Courses and Mathematical / Analytical Courses at p < .01 and Management Courses at p < .05. The data did not support professional designation having a significant effect on the desire to have Accounting Courses, Marketing Courses, Operations Management Courses and Foreign Language Fluency /International Management Courses in a business student‟s academic repertoire. As seen in Table 3, the means of the significant course areas show that educators placed more value on Finance Courses, Economics Courses, Humanities/ Liberal Arts Courses, and Mathematical/Analytical Courses within a business student‟s academic curriculum. Business Professionals placed more value on Management courses within an academic curriculum. Therefore, the results supported our conclusions drawn in Hypotheses 1 and 2. TABLE 2 TESTS OF MAIN EFFECTS AND TESTS OF BUSINESS PROFESSIONALS VS. EDUCATORS ON EACH AREA OF BUSINESS CURRICULUM USING UNIVARIATE F-TESTS IV Name DV Name Business/Education Wilks' Lambda Value (F) Univariate F .66 (5.36)*** Partial Eta2 .34 Accounting Courses --- 1.82 .02 Finance Courses --- 16.98*** .14 Economics Courses --- 22.51*** .18 Marketing Courses --- 1.14 .01 Management Courses --- 4.56* .04 Operations Management Courses --- .00 .00 Humanities/Liberal Arts Courses --- 12.17** .11 Mathematical / Analytical Courses --- 11.84** .10 Foreign Language Fluency / International Management --- 1.63 .02 Notes: ap < .10 *p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001 N = 105 TABLE 3 CELL MEANS AND STANDARD DEVIATIONS OF THE CONTENT AREAS OF BUSINESS CURRICULUM AS A FUNCTION OF BUSINESS PROFESSIONALS AND EDUCATORS Business Professionals and Educators Academic Areas Business Professionals Educators (n = 63) (n = 42) Accounting Courses 4.22 (.73) 4.42 (.71) Finance Courses 3.12 (.86) 3.80 (.78) Economics Courses 3.08 (.83) 3.86 (.81) Marketing Courses 3.48 (.90) 3.65 (.74) Management Courses 4.08 (.48) 3.82 (.79) Operations Management Courses 4.16 (.58) 4.17 (.59) Humanities / Liberal Arts Courses 2.83 (.70) 3.33 (.75) Mathematical / Analytical Courses 3.17 (.84) 3.68 (.57) Foreign Language Fluency / International Management 2.27 (.84) 2.49 (.90) 5. DISCUSSION Overall, our results supported both hypotheses. First, there was a significant difference in between what educators and business professionals perceive to be important in a business curriculum. Quite simply, educators and business professionals place a higher value on different content areas within a business student‟s academic curriculum. When assessing the individual academic content areas, professional designation accounted for approximately 34% of the variance, clearly a substantial proportion of the overall variance. In practical terms, professional designation accounts for a great deal of the difference in the perception of value of various content areas in academic curriculum. This finding supports our decision to explore more thoroughly the different perceptions of educators and business professionals on the value of different content areas within a business curriculum. Our second hypothesis on the value of analytic content areas was confirmed; educators placed a significantly stronger value on analytical courses than workforce business professionals. Educators placed a significantly higher value on most analytic course content, including finance, economics, and mathematical/analytic courses. This confirms statements by Bennis and O‟Toole (2005) and Quelch (2005) that there is a strong focus by educators on the analytic skills and not the softer side of management. Interestingly enough, business professionals placed a significantly higher value on managerial content in business curriculum. Looking at the results as a whole, it appears that educators are more focused on training a business student in how they need to mathematically analyze a problem, whereas business managers are looking for individuals coming out of a business program to have a good understanding of how to deal with people and the softer-side of management. One might even assume that businesses feel that they can train their employees in the analytical needs for the business, but need new employees to know how to deal with one another. This is even more eye-opening when looking at the diversified business sample that brought these results. Multiple industries, including the financial services industry where you would assume there would be a strong analytical focus, are represented. This indicates there needs to be a realignment of business curriculum to meets the needs of businesses. There were a few smaller findings from this study that bare mentioning. First, despite the significant differences in perception of value of analytic courses, there were no significant differences in the value of accounting courses between business professionals and educators. Educators did place a higher value on accounting courses within a curriculum over business professionals, however it was not significant. The most practical reason for this is possibly the inclusion of a managerial accounting course in the overall accounting course content. Business managers could have placed more value on the managerial accounting course due to a stronger managerial focus within the course. The other small finding that came out of this study is that despite the fact that managers valued managerial courses significantly higher than educators, they did not value humanities/liberal arts classes as high as educators. There are several obvious reasons for this significant difference. The most resonant is that managers are focused on softskills in management. They want to ensure that their new employees have a good understanding of how to deal with other individuals in their business and basic business issues. This does not necessarily include a basic understanding of humanities and world history. 6. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH We recognize that there are limitations with this study. First we acknowledge that as a correlational study no causality can be inferred from these results. However, due to the nature of content in this study, one can assume that a there is a correlation between the professional designations of business manager and educator and the differences in valuation of course content and the need for causality is limited. Limited concern can also be drawn from the significant correlations found between some of the variables. However, the analysis and the conclusions drawn from the findings really negate possible issues from this significance. For example, the significantly correlated analytical variables were analyzed as a whole in the conclusions drawn from this study. Based on our findings, our analysis, and our recognition of limitations, we suggest that further studies understanding what businesses desire in new hires will yield important information that can enhance understanding of and communication with the newest entrants to the workforce. Further qualitative examination, including interviews and observations, might identify specific components within business curriculum that are more valuable to businesses. Other studies might include understanding what practical experience in conjunction with education is needed in business curriculum along with studies understanding how values play into the effect of curriculum an employee success. We also suggest that surveys of former students may be a prime source for identifying crucial areas in need of scientific research. Findings from these investigations can be a prime source for strengthening the relevance of educational programs. 7. CONCLUSION All scholarship has a certain element of conceit and pretentiousness because its objective is to be the primary authority (Locke, 1996). However, in our opinion, the aspiration to be primary authority can be a central driver for high-quality research and effective curricula when it is augmented by the desire to assimilate the concerns of practitioners. Academic legitimacy is not sacrificed by linking science to practice (Pfeffer, 2007). The goal of education should be to use research to find evidence of cause-and-effect relationships and assist students in learning and applying what they have learned to their professional practice (Rousseau and McCarthy, 2007). B Schools should be concerned about enhancing and sustaining relevance and to do so they must develop educational programs that address the needs of practitioners (Beamish and Calof, 1989). Perhaps the words of Horace Secrist (1920), G. A. Warfield, (1931), and Lillian Gilbredth (1935) are as apropos today as they were decades ago when they recommended listening to the voices of practitioners in order to ensure B School relevance. REFERENCES Augier, Mie, "Making Management Matter: An Interview with John Reed”, Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5 (1), 2006, 84-100. Augier, Mie and March, James G., “The Pursuit of Relevance in Management Education”, California Management Review, 49 (3), 2007, 129-146. Beamish, Paul W. and Calof, Jonathan L., “International Business Education: A Corporate View”, Journal of International Business Studies, 20 (3), 1989, 553-564. Bennis, Warren.G. and O‟Toole, James, “How Business Schools Lost Their Way”, Harvard Business Review, May, 2005, 96-104. Bridgman, Todd, “Reconstituting Relevance: Exploring Possibilities for Management Educators‟ Critical Engagement with the Public”, Management Learning 38 (4), 2007, 425-439. Brotheridge, Celeste and Long, Stephen, “The „real-world‟ challenges of managers: implications for management education”, Journal of Management Development, 26 (9), 2007, 832-842. Bukics, Rose and Fleming, John, “New Hires”, Pennsylvania CPA Journal, 70, 1999, 22-27. Debnath, Sukumar C., Tandon, Sudhir, and Pointer, Lucille V., “Designing Business School Courses to Promote Student Motivation: An Application of the Job Characteristic Model”, Journal of Management Education, 31 (6), 2007, 812-831. Engwall, Lars, “The anatomy of management education” Scandinavian Journal of Management, 23, 2007, 4-35. Gilbreth, Lillian M., “What Do We Ask of Business Education?”, Journal of Educational Sociology, 8 (9) 1935, 549-554. Kleiman, Lawrence S. and Kass, Darrin, “Giving MBA Programs the Third Degree”. Journal of Management Education, 31(1) 2007, 81-103. Klimoski, Richard, “Introduction: Promoting the “Practice” of Learning From Practice”, Academy of Management Learning & Education, 6 (4), 2007, 493-494. Learmonth, Mark, “Critical Management education in Action: Personal Tales of Management Unlearning”, Academy of Management Learning & Education, 6 (1) 2007, 109-113. Levenburg, Nancy, “General Management Skills: Do Practitioners and Academic Faculty Agree on their Importance?” Journal of Education for Business, 72, 1996, 47-52. Lewis, D. and Ducharme, R., “The Education of Business Undergraduates: A gap in academic/practitioner expectations?” Journal of Education for Business, 66, 1990, 116-124. Locke, Robert. R., The collapse of the American management mystique, Oxford University Press, 1996. McGrath, Rita, “No Longer a Stepchild: How The Management Field Can Come Into Its Own”, The Academy of Management Journal, 50 (6) 2007, 1365-1378. Moore, J., “Education versus Training”, Journal of Chemical Education, 75 (2), 1998, 135. Pfeffer, Jeffrey, “A Modest Proposal: How We Might Change the Process and Product of Managerial Research”, Academy of Management Journal, 50 (6) 2007, 1334-1345. Pfeffer, Jeffrey and Fong, Christina T., “The End of Business Schools? Less Success Than Meets the Eye”, Academy of Management Learning and Education, 1(1) 2002, 79-95. Quelch, John, “A new agenda for business schools” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 52(15) 2005,B19. Rousseau, Denise M. and McCarthy, Sharon, “Educating Managers From An Evidence-Based Perspective”, Academy of Management Learning & Education, (6) 1, 2007, 84-101. Safon, Vicente, “Factors That Influence Recruiters‟ Choice of B-Schools and Their MBA Graduates: Evidence and Implications for B-Schools”, Academy of Management Learning & Education, 6 (2), 2007, 217-233. Schlesinger, Phyllis F., “Teaching and evaluation of an integrated curriculum”, Journal of Management Education, 20 (4) 1996, 479-490. Secrist, Horace, “Research in Collegiate Schools of Business”, The Journal of Political Economy, 28 (5) 1920, 353-374. Walker, Rhett H., Hanson, Dallas, Nelson, Lindsay and Fisher, Cathy, “A Case for more Integrative Multi-disciplinary Marketing Education”, European Journal of Marketing 32 (9/10) 1998, 803-812. Warfield, G. A., “Surveys of Schools of Business”, The Journal of Business of the University of Chicago, 4 (3) 1931, 78-87. Watson, Stephen R., “The Place for Universities in Management Education”, Journal of General Management, 19 (2),1993, :14-42.