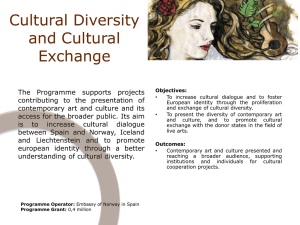

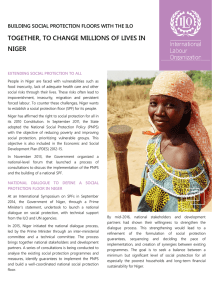

Economic and Social Councils in Latin America and the European

Anuncio