The situation of working-age people with disabilities across the EU

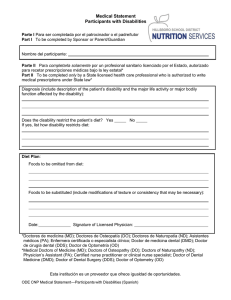

Anuncio