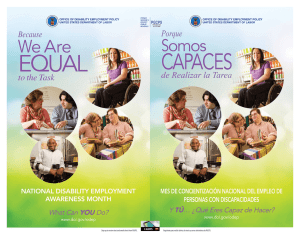

Acceptance ONE WAY OR ANOTHER Reactions toward disability

Anuncio

Acceptance ONE WAY OR ANOTHER Reactions toward disability vary. They depend on the person and the culture from which that person comes. In Mexican-American cultures, the expression “La vida es dura” [Life is hard] is often heard. Hardships, according to this view, are part of life to be endured with dignity and courage. Conditions that cannot be changed, such as health or disability, are to be accepted without blame or continual questioning. Life goes on. In El Paso, Texas, Marta Cofresi’s acceptance has been a springboard for her daughters’ well-rounded lives. Yo te quiero de una manera o de otra. Eres mi hija. Te acepto proque eres parte mia. When Marta Cofresi saw her newborn twin daughters, she said, “I accept you. And because I accept you, people will accept you.” Her words proved true. “Take your sisters for a walk, let them have some sunlight,” Marta used to say to her two older children, both a bit embarrassed about having sisters with cerebral palsy. After Marta would dress Roxela and Roxana in their prettiest clothes, the bashful brothers took them outside. Instead of being embarrassed, their brothers soon became proud to take those walks. Their friends liked seeing the girls in their nice outfits and would take turns pushing the girls in their baby carriages. Any activity, any occasion, any social appearance—Marta was there with her girls. That is how she introduced them to her community, and they soon became the center of every activity. Roxana and Roxela themselves learned that to have friends they would have to treat others as they themselves would like to be treated. Their mother also told them to accept that they would have to answer questions about their disability. “Por que te paso eso? Respondanles como paso todo. Aceptenlos tal como con.” Living with disability also meant believing in God and finding guidance from the Bible. As her children grew, Marta told them, “You are very special. Do what you can do, no more, no less.” Most of their school years were spent in special education classrooms. Then teachers in high school decided the girls would do well in general education classes. Roxana and Roxela Cofresi, now 19, have mental retardation (a diagnosis most people find hard to believe) and cerebral palsy. Roxana, highly verbal, uses crutches, and spends half her day in special education and half in regular education. Roxela has a more pronounced disability, can say some words, and uses a wheel chair. She spends six hours a day in special education. In one high school class, Roxela became acquainted with the captain of the football team. His mother, Roxela’s teacher, introduced them. The football player told his friends about “this nice girl” in his class and soon they became friends with Roxela. Ever since they have been little, all their activities are planned beforehand. This way they are busy and around several groups.” [Marta Cofresi] Said Irma Lorea, teacher, “I would invite Carlos, Bobby, and Adrian to eat with us, and say ‘hi’ from the hall. We got Roxela to say ‘Carlito’ and she would get real excited when Carlos came in. Roxela is very friendly. She’ll talk about anything with you, especially dating boyfriends, games, who she likes, who she doesn’t like.” In a short time, the boys were bringing Roxela candy, flowers, and other nice things. When they had to do school errands, the football players invited Roxela to ride along in the car. Many of Roxana’s friendships started in her leadership club—Vocational Industrial Clubs of America—where Roxana learns about electronics. This vocational club meets after school and on weekends. Members also have the opportunity to travel to other towns. Said Fernando Arias, club sponsor, “Right away I could tell Roxana was a natural-born leader. She communicates well with others. She’s outgoing. She’s friendly. This made it easy for her to make friends, in my class especially.” “She gained their respect through her leadership ability. She took charge—what needed to be done, she did. We participated in opening and closing ceremonies, and the other students realized she was the leader. When it came time to elect officers, they unanimously voted her president.” Saul, 19, fellow student, said, “Roxy always pays attention. She’s organized. Even her backpack is neat and nice. She’s smart, too. She doesn’t need my help for studying because she’s very smart. So I ask her for help when studying. I like helping her, too. She has other friends, too, not only me, who wait to see if she needs any help. She treats everybody nice. Everybody likes her.” The girls also have friendships outside school. They meet many people at church, football games, shopping malls, and other places. “Fuera de la escuela, ellas van a los football games. Y tambien tienen actividades en la iglesia,” Marta said. “Y en la iglesia tienen bastantes amigos, amigas, y salen. Inclusive tienen amistades que van de compras al mall.” “The Hispanic community has a tendency to be together because of big families and extended family,” Arias said, “This gives us a sense of bonding.” “Some people with the same disability don’t have friends. That’s why a parent needs to get involved like what Ms. Cofresi does. She takes her kids out and they communicate with the public. I’m sure Ms. Cofresi realizes the only way to get ahead is to go out and for it. Go out. Do it.” Yo te quiero de una manera o de otra. Eres mi hija. Te acepto porque eres parte mia.