- Ninguna Categoria

T7. Tipos de cambio: enfoque monetario

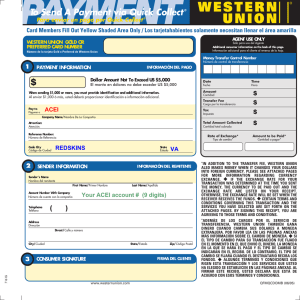

Anuncio

Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run T7: El tipo de cambio nominal: El modelo monetario con precios flexibles Carlos Llano Referencias: • Tema 5 del Programa. • Capítulo 3 de Feenstra&Taylor (2011) 1 Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 1 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model • A largo plazo el tipo de cambio se determina por la relación entre los niveles de precios en los dos países. Pero : ¿Qué determina los niveles de precios? • La teoría monetaria proporciona una respuesta: en el largo plazo, los niveles de precios se determinan en cada país por la demanda y la oferta de dinero. • Esta sección resume los elementos esenciales de la teoría monetaria y muestra cómo encajan en nuestra teoría de los tipos de cambio en el largo plazo. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 2 of 87 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run What Is Money? • El dinero tiene tres funciones en una economía: • Es un depósito de valor: ya que puede ser utilizado para comprar bienes y servicios en el futuro. Si el coste de oportunidad de tener dinero es bajo, vamos a mantener el dinero antes que otros activos menos líquidos (acciones, bonos, etc.). • Aporta una unidad de cuenta. • Es un medio de intercambio que nos permite comprar y vender bienes y servicios sin la necesidad de participar en el trueque. El dinero es el activo más líquido. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 3 of 87 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model The Measurement of Money FIGURE 14-4 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run The Measurement of Money This figure shows the major kinds of monetary aggregates (currency, M0, M1, and M2) for the United States from 2004 to 2010. Normally, bank reserves are very close to zero, so M0 and currency are virtually identical, but reserves spiked up during the financial crisis in 2008, as private banks sold securities to the Fed and stored up the cash proceeds in their Fed reserve accounts as a precautionary hoard of liquidity. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 4 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model The Demand for Money: A Simple Model • Las familias necesitan dinero para hacer transacciones. Por tanto depende del nivel de renta. • Un modelo sencillo para definir la Demanda de Dinero es la Teoría Cuantitativa del Dinero: d M Demand for money ($) L A constant PY Nominal income ($) Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 5 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model The Demand for Money: A Simply Model • Dividiendo el elemento anterior por los precios se obtiene la Demanda de Saldos Reales de una economía: d M L Y P A constant Real income Demand for real money • Mide el poder de compra de una moneda en términos de los bienes y servicios producidos en ella. • Es diréctamente proporcional a la renta real. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 6 of 87 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run Equilibrium in the Money Market El mercado de dinero está en equilibrio cuando la oferta de saldos reales es igual a la demanda de saldos reales. M L PY M LY P Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 7 of 87 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run A Simple Monetary Model of Prices • Una expresión para el nivel de precios en US y en EU: M US PUS LUSYUS M EUR PEUR LEURYEUR • Asumimos que en el largo plazo, los precios son flexibles y se ajustan según esta ecuación de equilibrio en el mercado de dinero. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 8 of 87 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model A Simple Monetary Model of Prices Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run FIGURE 14-5 Building Block: The Monetary Theory of the Price Level According to the LongRun Monetary Model In these models, the money supply and real income are treated as known exogenous variables (in the green boxes). The models use these variables to predict the unknown endogenous variables (in the red boxes), which are the price levels in each country. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 9 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model A Simple Monetary Model of the Exchange Rate Si “enchufamos” la expresión anterior de precios, a la equación vista anterior acerca de la PPA absoluta, obtenemos que: M US L Y M US / M EUR PUS US US E$/ EU M EUR LUS YUS / LEUR YEUR PE Exchange rate Ratio of price levels LEUR YEUR Relative nominal money supplies (14-3) divided by relative real money demands Esta es la ecuación fundamental para la “teoría monetaria de los tipos de cambio a largo plazo” Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 10 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model Money Growth, Inflation, and Depreciation Las implicaciones de la ecuación fundamental del enfoque monetario de tipos de cambio son intuitivos: Supongamos que, todo lo demás igual, aumenta la oferta de dinero de Estados Unidos. Se produce un aumento en la oferta de dinero nominal en EEUU en relación con EU (lado derecho) ; esto causa el aumento del tipo de cambio (el dólar se deprecia frente al euro). Ahora supongamos que aumenta la renta real de EE.UU. El lado derecho de la igualdad disminuye, (aumenta la demanda real de dinero americano respecto al europeo), haciendo que el tipo de cambio caiga (el dólar de EE.UU. se aprecia frente al euro). Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 11 of 87 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run Money Growth, Inflation, and Depreciation La oferta de dinero americana: MUS, y la tasa de crecimiento de la masa monetaria americana es μUS: US ,t M US ,t 1 M US ,t M US ,t Rate of money supply growth in U.S. La tasa de crecimiento de la renta real americana es gUS: gUS ,t YUS ,t 1 YUS ,t YUS ,t Rate of real income growth in U.S. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 12 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model Money Growth, Inflation, and Depreciation Mezclando lo anterior, la tasa de crecimiento de los precios − en US, será: PUS =MUS/LUSYUS la diferencia entre las tasas de crecimiento de la masa monetaria (μUS ) menos la de la renta real (gUS). El crecimiento de los precios en usa es us tasa de inflación: πUS. Por tanto: US,t US,t gUS,t (14-4) De forma equivalente, para Europa tenemos que: EUR,t EUR,t gEUR,t (14-5) Cuando el crecimiento de la masa monetaria es superior a la de la renta real, tenemos más dinero para menos bienes, y eso crea inflación. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 13 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model Money Growth, Inflation, and Depreciation Combinando la Eq (14-4) y la Eq (14-5), resolvemos ahora para los diferenciales de inflación y obtenemos una expresión que predice la tasa de depreciación del tipo de cambio: E$ / € t US ,t EUR ,t US ,t gUS ,t EUR ,t g EUR ,t (14-6) E$ / € ,t Inflation differential Rate of depreciation of the nominal exchange rate US ,t EUR ,t gUS ,t g EUR ,t . Differential in nominal money supply growth rates Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. Differential in real output growth rates 14 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 2 Money, Prices, and Exchange Rates in the Long Run: Money Market Equilibrium in a Simple Model Money Growth, Inflation, and Depreciation Las consecuencias de la ecuación anterior son importantes: ■ Si EEUU aplica una política monetaria en el largo plazo que es superior al crecimiento de la renta real, el Dolar tenderá a depreciarse más rapidamente. ■ Si EEUU aplica una política monetaria en el largo plazo que es inferior al crecimiento de la renta real, el Dolar tenderá a apreciarse. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 15 of 87 3 The Monetary Approach: Implications and Evidence Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model • Cuando queremos predecir el comportamiento del tipo de cambio en el futuro, nos preguntamos: • Qué recorrido seguirá si los precios son flexibles y la PPA se cumple? Forecasting Exchange Rates: An Example • Asumimos que U.S. y EU tienen un crecimiento de renta real nulo: 0%. • EU tiene un nivel de precios constante, por lo que su inflación es cero. • Analicemos dos casos: Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 16 of 87 3 The Monetary Approach: Implications and Evidence Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model Forecasting Exchange Rates: An Example Caso 1: Incremento puntual en la masa monetaria USA: a. 10% de incremento en M. b. Los saldos reales M/P se mantienen constantes, porque la renta real se mantiene constante. c. Por tanto, P y M se mueven en la misma proporción, por lo que habrá un incremento del 10% en el nivel de precios P. d. Según la PPA, el tipo de cambio E y los precios P se mueven en la misma proporción. Por tanto, se produce un aumento del 10% en E: por tanto, el dolar se deprecia un 10%. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 17 of 87 3 The Monetary Approach: Implications and Evidence Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model Forecasting Exchange Rates: An Example Caso 2: Un incremento en la tasa de crecimiento de la masa monetaria en USA. La tasa de crecimiento de la masa monetaria era fija y con valor μ. En un momento T , US incrementa esta tasa hasta μ + ∆μ. a. La masa monetaria real M/P se mantiene constante, como antes. c. Por tanto, los precios P y M se mueven en igua proporción. d. La PPA implica que el tipo de cambio E y los precios P se mueven proporcionalmente, luego E sigue siendo un múltiplo constante de P (y d M). Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 18 of 87 3 The Monetary Approach: Implications and Evidence Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model Forecasting Exchange Rates: An Example FIGURE 14-6 (1 of 4) Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run An Increase in the Growth Rate of the Money Supply in the Simple Model Before time T, money, prices, and the exchange rate all grow at rate μ. Foreign prices are constant. In panel (a), we suppose at time T there is an increase ∆μ in the rate of growth of home money supply M. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 19 of 87 3 The Monetary Approach: Implications and Evidence Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model Forecasting Exchange Rates: An Example FIGURE 14-6 (2 of 4) Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run An Increase in the Growth Rate of the Money Supply in the Simple Model (continued) In panel (b), the quantity theory assumes that the level of real money balances remains unchanged. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 20 of 87 3 The Monetary Approach: Implications and Evidence Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model Forecasting Exchange Rates: An Example FIGURE 14-6 (3 of 4) Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run An Increase in the Growth Rate of the Money Supply in the Simple Model (continued) After time T, if real money balances (M/P) are constant, then money M and prices P still grow at the same rate, which is now μ + ∆μ, so the rate of inflation rises by ∆μ, as shown in panel (c). Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 21 of 87 3 The Monetary Approach: Implications and Evidence Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the Simple Model Forecasting Exchange Rates: An Example FIGURE 14-6 (4 of 4) Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run An Increase in the Growth Rate of the Money Supply in the Simple Model (continued) PPP and an assumed stable foreign price level imply that the exchange rate will follow a path similar to that of the domestic price level, so E also grows at the new rate μ + ∆μ, and the rate of depreciation rises by ∆μ, as shown in panel (d). Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 22 of 87 APPLICATION Evidence for the Monetary Approach FIGURE 14-7 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run Inflation Rates and Money Growth Rates, 1975–2005 This scatterplot shows the relationship between the rate of inflation and the money supply growth rate over the long run, based on data for a sample of 76 countries. The correlation between the two variables is strong and bears a close resemblance to the theoretical prediction of the monetary model that all data points would appear on the 45-degree line. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 23 of 87 APPLICATION Evidence for the Monetary Approach Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run FIGURE 14-8 Money Growth Rates and the Exchange Rate, 1975–2005 This scatterplot shows the relationship between the rate of exchange rate depreciation and the money growth rate differential relative to the United States over the long run, based on data for a sample of 82 countries. The data show a strong correlation between the two variables and a close resemblance to the theoretical prediction of the monetary approach to exchange rates, which would predict that all data points would appear on the 45-degree line. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 24 of 87 APPLICATION Hyperinflations of the Twentieth Century Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run Economists traditionally define a hyperinflation as a sustained inflation of more than 50% per month. HEADLINES The First Hyperinflation of the Twenty-First Century By 2007 Zimbabwe was almost at an economic standstill, except for the printing presses churning out the banknotes. A creeping inflation—58% in 1999, 132% in 2001, 385% in 2003, and 586% in 2005—was about to become hyperinflation, and the long-suffering people faced an accelerating descent into even deeper chaos. Three years later, shortly after this news report, the local currency disappeared from use, replaced by U.S. dollars and South African rand. Ink on their hands: Under President Robert Mugabe and Central Bank Governor Gideon Gono (seen clutching a Z$50 million note), Zimbabwe became the latest country to join a rather exclusive club. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 25 of 87 APPLICATION Hyperinflations of the Twentieth Century Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run Currency Reform Hyperinflations help us understand how some currencies become extinct if they cease to function well and lose value rapidly. Dollarization in Ecuador is a recent example. A government may then redenominate a new unit of currency equal to 10N (10 raised to the power N) old units. Sometimes N can get quite large. In the 1980s, Argentina suffered hyperinflation. On June 1, 1983, the peso argentino replaced the (old) peso at a rate of 10,000 to 1. Then on June 14, 1985, the austral replaced the peso argentino at 1,000 to 1. Finally, on January 1, 1992, the convertible peso replaced the austral at a rate of 10,000 to 1 (i.e., 10,000,000,000 old pesos). In 1946 the Hungarian pengö became worthless. By July 15, 1946, there were 76,041,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 pengö in circulation. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 26 of 87 APPLICATION Hyperinflations of the Twentieth Century PPP in Hyperinflations Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run FIGURE 14-9 The data show a strong correlation between the two variables and a very close resemblance to the theoretical prediction of PPP that all data points would appear on the 45-degree line. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. Inflation Rates and Money Growth Rates, 1975–2005 The scatterplot shows the relationship between the cumulative start-tofinish exchange rate depreciation against the U.S. dollar and the cumulative start-tofinish rise in the local price level for hyperinflations in the twentieth century. Note the use of logarithmic scales. 27 of 87 APPLICATION Hyperinflations of the Twentieth Century Money Demand in Hyperinflations Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run FIGURE 14-10 The Collapse of Real Money Balances during Hyperinflations This figure shows that real money balances tend to collapse in hyperinflations as people economize by reducing their holdings of rapidly depreciating notes. The horizontal axis shows the peak monthly inflation rate (%), and the vertical axis shows the ratio of real money balances in that peak month relative to real money balances at the start of the hyperinflationary period. The data are shown using log scales for clarity. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 28 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model • El problema con la teoría cuantitativa utilizada hasta aquí es que asume que la demanda de dinero es estable, y esto no es plausible. • En esta sección, se explora un modelo más general que permita la demanda de dinero varíe con el tipo de interés nominal. • Consideramos que los vínculos entre la inflación y el tipo de interés nominal en una economía abierta, y luego volvemos a la cuestión de la mejor manera de entender lo que determina los tipos de cambio en el largo plazo. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 29 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model The Demand for Money: The General Model • Ahora el tipo de interés recoge el coste de oportunidad de tener activos líquidos no rentables (dinero) • Un aumneto en el tipo de interés reduce la demanda de dinero: d M Demand for money ($) L(i ) P Y A decreasing function Nominal income ($) • Dividiendo por P, tenemos: Md P Demand for real money L(i ) Y Real A decreasing function Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. income 30 of 87 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model The Demand for Money: The General Model Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run FIGURE 14-11 The Standard Model of Real Money Demand Panel (a) shows the real money demand function for the United States. The downward slope implies that the quantity of real money demand rises as the nominal interest rate i$ falls. Panel (b) shows that an increase in real income from Y1US to Y2US causes real money demand to rise at all levels of the nominal interest rate i$. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 31 of 87 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model Long-Run Equilibrium in the Money Market Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run M P Real money supply (14-7) L(i )Y Real money demand Inflación y Tipos de Interés en el Largo Plazo • Ahora mezclamos la PPA y la PDI : • Obtenemos una expresión importante para analizar los tipos de interés en las economías abiertas: E$/e € E$/ € Tasa de depreciación esperada del dolar e e EUR US Diferencial esperado de inflación E$/e € E$/ € y Tasa de depreciación esperada del dolar Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. i$ Tipo de interés neto del dolar (moneda local) i€ Tipor de interés neto del euro (divisa) 32 of 87 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model The Fisher Effect Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run • Las diferencias nominales de tipos de interés igualan a los diferenciales de inflación: i$ i€ Nominal interest rate differential e e US EUR Nominal inflation rate differential (expected) • Todo lo demás constante, un incremento en la tasa esperada de inflación llevará a un incremento equivalente en su tipo de interés nominal. • Este es el Efecto Fisher. • Implica que el cambio en el coste de oportunidad de mantener dinero (i), es igual no sólo al cambio en el tipo de interés nominal, sino también al cambio en la inflación. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 33 of 87 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model Real Interest Parity • Reordenando la última ecuación, tendremos que: Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run e i$ US i€ eEUR (14-8) • Cuando la tasa de inflación (π) es restada al tipo de interés nominal (i), obtenemos el tipo de interés real (r), esto es, el tipo de interés corregido de inflación. r r e US e EUR • Resultado importante: si la PPA y la PDI se cumplen, entonces los tipos de interés reales esperados entre los dos países se igualan. Esta es la paridad del interés real. • Esto implica que: El arbitrage en los mercados de bienes y financieros es suficiente, en el largo plazo, para promover una igualación de los tipos de interés reales entre países. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 34 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model Real Interest Parity • En el Largo Plazo, todos los paíse compartirán un tipo de interés real esperado equivalente: r r e US e EUR r * (14-9) • Por tanto, podemos tomar r* como dado, como variable exógena, algo que escapa al control de la política monetaria y a la acción de un país particular. • Bajo estas condiciones, el efecto Fisher es aun más claro, ya que, por definición: e e i$ rUSe US r * US , Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. e i€ rEUR eEUR r * eEUR . 35 of 87 APPLICATION Evidence on the Fisher Effect Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run FIGURE 14-12 Inflation Rates and Nominal Interest Rates, 1995–2005 This scatterplot shows the relationship between the average annual nominal interest rate differential and the annual inflation differential relative to the United States over a ten-year period for a sample of 62 countries. The correlation between the two variables is strong and bears a close resemblance to the theoretical prediction of the Fisher effect that all data points would appear on the 45-degree line. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 36 of 87 APPLICATION Evidence on the Fisher Effect Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run FIGURE 14-13 Real Interest Rate Differentials, 1970–1999 This figure shows actual real interest rate differentials over three decades for the United Kingdom, Germany, and France relative to the United States. These differentials were not zero, so real interest parity did not hold continuously. But the differentials were on average close to zero, meaning that real interest parity (like PPP) is a general long-run tendency in the data. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 37 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model The Fundamental Equation under the General Model • Este modelo se diferencia del anterior más sencillo (basado en la Teoría Cuantitativa) sólo en permitir que L dependa de i. M US L i Y ( ) M US / M EUR PUS US $ US (14-10) E$ / € PEUR M EUR LUS (i$ )YUS / LEUR (i )YEUR Exchange rate Ratio of price levels Relative nominal money supplies LEUR (i )YEUR divided by Relative real money demands • Ahora, sólo cuando varíen los tipos de interés nominales, el modelo genera conclusiones diferentes. Por tanto, este modelo general subsume el anterior cuando los tipos no varían. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 38 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model • Ahora reexaminamos el problema de predicción para el caso en el que hay un aumento en la tasa de crecimiento del dinero en EE.UU. • Planteamos que en el momento T, Estados Unidos estaba aumentando la tasa de crecimiento de la oferta de dinero desde un tipo fijo μ a una tasa ligeramente superior μ + ∆μ. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 39 of 87 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model FIGURE 14-14 (1 of 4) Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run An Increase in the Growth Rate of the Money Supply in the Standard Model Before time T, money, prices, and the exchange rate all grow at rate μ. Foreign prices are constant. In panel (a), we suppose at time T there is an increase ∆μ in the rate of growth of home money supply M. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 40 of 87 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model FIGURE 14-14 (2 of 4) Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run An Increase in the Growth Rate of the Money Supply in the Standard Model (continued) This causes an increase ∆μ in the rate of inflation; the Fisher effect means that there will be a ∆μ increase in the nominal interest rate; as a result, as shown in panel (b), real money demand falls with a discrete jump at T. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 41 of 87 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model FIGURE 14-14 (3 of 4) Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run An Increase in the Growth Rate of the Money Supply in the Standard Model (continued) If real money balances are to fall when the nominal money supply expands continuously, then the domestic price level must make a discrete jump up at time T, as shown in panel (c). Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 42 of 87 4 Money, Interest Rates, and Prices in the Long Run: A General Model Exchange Rate Forecasts Using the General Model FIGURE 14-14 (4 of 4) Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run An Increase in the Growth Rate of the Money Supply in the Standard Model (continued) Subsequently, prices grow at the new higher rate of inflation; and given the stable foreign price level, PPP implies that the exchange rate follows a similar path to the domestic price level, as shown in panel (d). Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 43 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 4 Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes • Un aspecto principal de la política económica de un país es el deseo de mantener la inflación dentro de ciertos límites. Para lograr tal objetivo requiere que los políticos estén sujetos a algún tipo de restricción en el largo plazo. Tales restricciones son llamados anclas nominales. • El anclaje nominal a “largo plazo” y la flexibilidad a corto plazo son las características del marco de políticas que los economistas llaman el “régimen monetario de un país”. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 44 of 87 Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run 4 Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes The Long Run: The Nominal Anchor Volvemos a etiquetar nuestros países como Home (H) y Foreign (F). Consideramos 3 “ánclas nominales”: objetivos de tipo de cambio; objetivos de oferta monetaria; objetivos de tipos de interés. ■ Objetivos de Tipos de cambio: • Si la PPA relativa establece que la inflación nacional depende de la tasa de depreciación de la moneda y la inflación externa (exógena), una manera de “anclar nuestra inflación” es establecer una tasa de depreciación constante de la moneda local. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 45 of 87 4 Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run The Long Run: The Nominal Anchor ■ Objetivo de la Masa Monetaria: • Otra alternativa, sería establece una tasa constante de crecimiento de la Masa Monetaria, por ejemplo, del 2% anual. • Aquí el problema lo plantea el último elemento: la tasa de crecimiento de la renta real puede ser inestable y difícil de conocer. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 46 of 87 4 Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run The Long Run: The Nominal Anchor ■ Objetivos de Tipos de Interés: e Home iHome Tipo _ de int erés no min al Ancla • • • r* Tipode int erés rea l no min al El Efecto Fisher dice que la inflación en Home surge de la diferencia entre el tipo de interés nombial en Home y el tipo de interés real extranjero. Si el último se asume como constante, entonces, si mantenemos contstante nuestro tipo de interés nominal, la inflación se mantendrá constante. Este “ancla nominal” está siendo utilizada cada vez con más asiduidad. Asumir un tipo de interés real para el mundo no es una mala hipótesis. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 47 of 87 4 Monetary Regimes and Exchange Rate Regimes Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run TABLE 14-2 Exchange Rate Regimes and Nominal Anchors This table illustrates the possible exchange rate regimes that are consistent with various types of nominal anchors. Countries that are dollarized or in a currency union have a “superfixed” exchange rate target. Pegs, bands, and crawls also target the exchange rate. Managed floats have no preset path for the exchange rate, which allows other targets to be employed. Countries that float freely or independently are judged to pay no serious attention to exchange rate targets; if they have anchors, they will involve monetary targets or inflation targets with an interest rate policy. The countries with “freely falling” exchange rates have no serious target and have high rates of inflation and depreciation. It should be noted that many countries engage in implicit targeting (e.g., inflation targeting) without announcing an explicit target and that some countries may use a mix of more than one target. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 48 of 87 APPLICATION Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run Nominal Anchors in Theory and Practice An appreciation of the importance of nominal anchors has transformed monetary policy making and inflation performance throughout the global economy in recent decades. In the 1970s, most of the world was struggling with high inflation. In the 1980s, inflationary pressure continued. In the 1990s, policies designed to create effective nominal anchors were put in place in many countries. Most, but not all, of those policies have turned out to be credible, too, thanks to political developments in many countries that have fostered central-bank independence. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 49 of 87 APPLICATION Nominal Anchors in Theory and Practice Chapter 14: Exchange Rates I: The Monetary Approach in the Long Run TABLE 14-3 Global Disinflation Cross-country data from 1980 to 2004 show the gradual reduction in the annual rate of inflation around the world. This disinflation process began in the advanced economies in the early 1980s. The emerging markets and developing countries suffered from even higher rates of inflation, although these finally began to fall in the 1990s. Copyright © 2011 Worth Publishers· International Economics· Feenstra/Taylor, 2/e. 50 of 87

Anuncio

Descargar

Anuncio

Añadir este documento a la recogida (s)

Puede agregar este documento a su colección de estudio (s)

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizadosAñadir a este documento guardado

Puede agregar este documento a su lista guardada

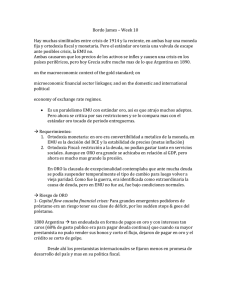

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizados