Perspectives on Religious Freedom in Spain

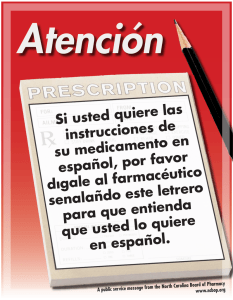

Anuncio