`Con nuestro propio esfuerzo`: Understanding the Relationships

Anuncio

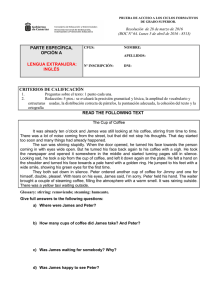

European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 93, October 2012 | 25-40 ‘Con nuestro propio esfuerzo’: Understanding the Relationships between International Migration and the Environment in Guatemala Mariel Aguilar-Støen Abstract: International migration from rural areas affects the environment in numerous and complex ways. The inflow of economic and social remittances changes production and consumption patterns, social relations, and social and economic institutions in the places of origin of migrants. In this case study, I discuss how migration is pushing a local process of land redistribution in Guatemala. Such a process is also changing patterns of land use and land cover. The process is influenced by the emergence of local cooperatives, which in turn are stimulated by organizations and networks in wider temporal and spatial contexts. Land acquisition by migrant families has also improved their position vis-àvis traditional landowners. My study suggests that in contexts where local organization is successful and linked to actors and networks at wider scales, transnational households are in a good position to negotiate the outcomes of the use of remittances. These families are improving their living standards without degrading the environment irreversibly. Keywords: migration, Guatemala, land-use change, environment, cooperatives. In 2011, 214 million international migrants were remitting an estimated 414 billion dollars to their countries of origin on a global scale (IOM 2011). Approximately 10 per cent of Guatemala’s population work abroad and remittances account for 10 per cent of the national GDP, constituting the largest single source of foreign income to the country (BANGUAT 2011; PNUD 2010). It is reasonable to expect that inflows of new capital from remittances are affecting the environment of the places from which Guatemalans are migrating. Migration affects the environment in several ways. Remittances change production and consumption patterns, affect social relations and social and economic institutions in the places of origin of migrants (Curran 2002; Moran-Taylor and Taylor 2010), and affect the asset base with which households build their livelihoods. What is the effect of migration and remittances on land tenure, land use, and the environment? This paper addresses this question focusing on how households gain and secure access to resources and networks, and how such access affects the environment. In this paper, environment refers to natural resources including agriculture and forests (Moran-Taylor and Taylor 2010). I argue that migration is fostering a process of land redistribution. From a situation in which land was concentrated in the hands of a few powerful landowners, now more households have acquired land both for agricultural production and for house building. Access to land has been mediated by access to at least three broader networks: migrant networks, national producers’ organizations, and money-transfer operators and banks. Households secure their access to some of these networks by membership in the local cooperative. As also non-migrants are members of the cooperative, the effects of changing agricultural production are also evident in these types of households. Some patterns of inequality have been broken within the community, particularly those which concern access to land, credit, and technical assistance. Published by CEDLA – Centre for Latin American Research and Documentation | Centro de Estudios y Documentación Latinoamericanos, Amsterdam; ISSN 0924-0608; www.cedla.uva.nl 26 | Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 93, octubre de 2012 However, households without membership in the cooperative have not reaped the same benefits as those who are members, and some household members remain excluded from certain activities. This is particularly the case for women. I spent six months of fieldwork between October 2009 and January 2011 in Santa Teresa, Guatemala. During my fieldwork I combined standard qualitative methods and conducted two surveys with the help of eight field assistants.1 The GIS laboratory of the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala analysed, using standard methods, satellite images from 1990, 2000, 2006, and 2010. The paper is organized as follows: in the first section I describe the conceptual background and approach framing my study. This section is followed by a description of the background of the place where my study was conducted and of the origins of the local cooperative. The third section analyses changes in land tenure and land use, and the fourth section analyses the non-material dimensions of changes in land tenure and land use. This section is followed by a conclusion. Migration, remittances, and the environment: The approach of this study It has been hypothesized that migration would lead to the abandonment of agriculture due to lost labour, which would materialize in large amounts of agricultural land turning into fallows and eventually forest (Lambin and Meyfroidt 2011). This hypothesis ignores the possibility that labour could be substituted by household members, sharecroppers, hired workers, or mechanization (Hein 2006), or by turning to less labour-intensive, but more land-intensive agricultural activities, e.g. cattle ranching (Schmook and Radel 2008). The empirical literature shows that migration can result in deforestation or reforestation in the areas of origin of migrants, depending on the investments made by households, markets, policies, and institutions (Conway and Lorah 1995; Hecht et al. 2006; Holder and Chase 2011; Kull et al. 2007; Moran-Taylor and Taylor 2010; Naylor et al. 2002; Taylor et al. 2006). It also shows that migration might affect patterns of land tenure (Hein 2006; Taylor et al. 2006; Zoomers 2010). It might weaken agricultural production in general and food production in particular (Moran-Taylor and Taylor 2010), or it might not affect them in significant ways (Gray 2009; Jokisch 2002; Schmook and Radel 2008). The evidence on the effects of remittances on land use is so far insufficient to draw generalizations (Lambin and Meyfroidt 2011). This might be because the effects of migration on the environment could become evident only after certain household needs such as food, clothing, and education have been met (Massey et al. 1987). Santa Teresa is a good site for studying the effects of migration on the environment. The almost forty years that have passed since migration started in Santa Teresa may have given migrant households the opportunity to fulfil their more immediate needs, and to accumulate some capital for investing in land-related activities, or in non-farm activities. To better understand the effects of migration on the environment, this paper focuses not only on the outcomes (i.e. how the effects materialize in the landscape), but also on the role of networks and social capital in mediating such changes. Some suggest that focusing on networks and social capital will allow for better understanding of the links between migration and the environment (Curran 2007). Migration and remittances could contribute to building more sustainable livelihoods, increase the re- European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 93, October 2012 | 27 source base, and improve the opportunities of households of using their assets for improving their living standards. Organizations and networks seem to play a central role in supporting migrant localities to renegotiate relationships with the market, and with state and non-state actors. Such new relationships can result in new resources, entitlements, and opportunities that facilitate the emergence of local processes of agricultural intensification, or the establishment of non-agricultural activities that can ameliorate both poverty and environmental degradation (Bebbington 1997, 1999). I pay special attention to the ability (or lack of ability) of households and their members to sustain and increase access to resources (i.e. credit, land, skills, labour) and to networks, social organizations, state and non-governmental organizations, and market actors. Access refers to the use or acquisition of resources and the beneficial exploitation of livelihood opportunities (de Haan and Zoomers 2005). Access is mediated by social relations (i.e. age, gender, class, ethnicity, religion) and institutions (i.e. laws, property rights, markets). Organizations (i.e. government agencies, NGOs, cooperatives, private companies) are groups of individuals joined for the purpose of achieving certain objectives (Ellis 2000) . Access to resources is key for transforming people’s livelihoods, but accessing resources happens within the context of social relations and transactions between household members and other actors. In trying to access resources, people engage in relationships with local and more distant actors in broader temporal and spatial scales (Ellis 2000). Some suggest that access to other actors comes prior to access to material resources in the determination of livelihood strategies (Bebbington 1999; Ellis 2000). What we observe in Santa Teresa today is influenced by the effect of previous initiatives and organizations, and by projects and organizations that are not physically present in the town at all times. Another approach suggests two dimensions of access to networks. The first one is horizontal connections which allow people ‘to get by’. The second is vertical connections which allow them ‘to get ahead’, also referred to as ‘bonding’ and ‘bridging’ social capital (Woolcock and Narayan 2000). Different combinations of vertical and horizontal connections will result in different outcomes (Woolcock and Narayan 2000), some of which would materialize in the landscape. Having access to networks or to other actors alone would not determine the direction of environmental change. Other assets in the household (e.g. education, labour, skills, capital) would influence environment-related decisions. In this essay I will look at how access to networks and organizations affects the ability of households to increase their assets and how this affects the environment. Previous empirical work suggests that the impacts of migration are manifested not only in migrant households. Investments such as in land, production, health, education, house building, and small business can have a positive multiplier effect through which the benefits of remittances might also accrue to non-migrant households (Hein 2006), especially if non-migrant households have access to networks and organizations. Santa Teresa Santa Teresa2 is located in the Santa Rosa valley in eastern Guatemala. According to the last population census, 1,806 persons (849 males and 958 females) lived 28 | Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 93, octubre de 2012 there as of 2002 (INE 2002). Almost 99 per cent of the population consider themselves Ladinos.3 This part of Guatemala has been referred to as the ‘Forgotten East’. Despite facing serious economic, environmental, social, and security challenges, this area has not attracted much attention from researchers, policy makers, or non-governmental organizations (Moran-Taylor 2008). The land of Santa Teresa lies in an altitudinal range between 1,000 and 1,500 m.a.s.l. The soils and rainfall patterns are suitable for agriculture. The territory where Santa Teresa is located has a long settlement history, starting before the Spanish invasion (Letona Zuleta et al. 2003). During the colonial period the land of what today constitutes Santa Teresa was allocated as an encomienda (Certificación 1873),4 and later to a family of Spanish descent, the Solares (AFEHC 2007), whose members maintained control over the land and the landless population until late in the twentieth century. Consequently land-use decisions were mostly made by the owner of the finca. Land was dedicated to coffee production, sugarcane, wheat, and extensive cattle ranching. Profits from agricultural production remained in the hands of large landowners and little was invested in improving the infrastructure of the community or the living conditions of the workers. The situation has since radically changed. More families own land, areas dedicated to cattle ranching have been converted to coffee, and more families are involved in other economic activities like small businesses, construction, and commercialization of dairy products. Migration started in Santa Teresa in the late 1960s. Today approximately 50 per cent of the households have a relative living abroad, mainly in California. The structure of the population in Santa Teresa reflects the increased participation of young males in migration: 50 per cent of the population is in the age range between 0-20 years (of these 65 per cent are women), only 1 per cent is in the age class 3140 (64 per cent of these are women), and 9 per cent are in the range between 41 and 50 years of age. Compared to previous decades, a far higher percentage of the population now has access to education and to credit and savings, lives in better houses, and has access to health care. Furthermore, although poverty is still a widespread problem, Santa Teresa scores higher than the national average on the Human Development Index (0.625 for Santa Teresa and 0.525 for the country in 2002, as reported by UNDP). How can this transformation be explained? This transformation is the result of the ways in which households in Santa Teresa have changed their livelihood strategies. This change has happened within the context of structural changes in the national political economy, international markets, organized interventions, and demographic change. Shifting policies are important in explaining these changes. Two other related factors are worth considering. The first one is the role played by local institutions, which has been strengthened by the links these institutions have developed to national and international organizations. These links are reinforced also by the process of international migration and the inflow of economic and social remittances to the community. From finca to cooperative Guatemala is characterized by extremely unequal patterns of land distribution; approximately 2 per cent of the population owns approximately 80 per cent of arable land (Gauster and Isakson 2007; PNUD 2010). Access to land has been contested European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 93, October 2012 | 29 for centuries in the country. In this context, numerous cooperatives were organized from the 1940s onwards with the aim of improving access to land, credit, markets, and other services; and the cooperative movement became an important base for peasant organization in Guatemala (Anderson 1988). By 1976 there were 510 cooperatives functioning in Guatemala (Lyon 2007; Stølen 2007). Cooperative formation was supported by the state and by international development agencies, especially USAID and the Catholic Church. During the 1970s the Church, influenced by the spirit of ‘Liberation Theology’, embarked on development projects in different parts of the country (Stølen 2007). The Church in Santa Teresa has promoted ideals linked to ‘communitarian organization’, broad participation in decisionmaking in the community, and education. In the 1960s priests and nuns engaged in literary courses and offered training through a farmers’ school (escuela campesina). By the early 1990s the farmers’ school was transformed into a non-profit private high-school, which continues to be run by the nuns today. The school has a special scholarship programme for girls from low-income households. An agrarian cooperative was established in Santa Teresa in the 1960s, although it did not last long. The aim of the cooperative was to support small-scale agricultural production, much of which occurred in rented lands. Although land did not change hands in significant ways during that time, the cooperative served as a channel through which campesinos got in contact with other organizations. One of them was the National Reconstruction Committee (CRN) created after an earthquake in 1976. The CRN was in charge of orienting and coordinating the reconstruction of the country to promote economic development (FAO 1994). In Santa Teresa the CRN had a local committee in which many of the members of the cooperative were involved. Another important contact was with the Guatemalan Peasant Federation (Federación Campesina de Guatemala – FCG). Tereseños participated in activities organized by the FCG including training as ‘community developers’, visits to similar organizations in other countries, meetings, assemblies, etc. With time they came to occupy leadership positions within the FCG. The Esperanza cooperative started its modest operations in 1986 as a savings and credit cooperative with 30 associates. Fifteen members of the cooperative bought an old cattle finca (large estate) in the neighbouring town. Land was later divided into fifteen parcels owned individually by an equal number of associates, and coffee was planted. At the same time Santa Teresa witnessed the departure of many of its sons. During the 1980s young men sought ways of escaping recruitment into forced military service, which exclusively targeted poorer boys in the town. Tobacco production collapsed when the National Tobacco Company, owned by British American Tobacco, terminated its contracts with local farmers in the 1980s, resulting in a surplus of labour in many households. Tobacco is a very labour-intensive cash crop suitable for smallholders relying on family labour (Chapman and Wong 1990). The factors above, together with the devaluation of the Guatemalan currency (in 1986 the exchange rate was changed from parity with the U.S. dollar to 2.5 Quetzales per US$ 1 (Morán Samayoa 2011)), acted as push factors for the migration of young men. Many regularized their migratory situation with the amnesty granted to agricultural workers through the Special Agricultural Workers Program (SAW) in 1986, or they were granted political asylum. With this, 30 | Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 93, octubre de 2012 the doors for family reunification of Tereseños were opened and the process of migration firmly established in the community. The material dimension: changes in land tenure and land use One of the most evident features of present-day Santa Teresa is the increased urbanization of the town centre. Close to the settlement centre, houses scattered alongside milpa fields occupy an area previously devoted to agriculture. Migrant households have built their houses in land previously used for coffee production and until recently belonging to the Solares family. A high percentage of migrant households (44 per cent) owns the house in which they live (for non-migrants the figure is 30 per cent). In their newly acquired plots, they build a house and reserve an area for maize cultivation and for keeping animals to feed the family. In addition to being essential for starting a family, building a house was spoken of by my interviewees as important to overcoming a sense of deprivation that had been experienced previously. As Carranza explains, ‘When you have only eaten beans once a day all your life, and suddenly you have the opportunity of eating meat, you try to eat meat three times a day. You try to eat as much as you can because you could not do it before; it was a luxury only others could afford…. It is the same thing with the houses and the cars’. Turning agricultural land into urban plots seems a logical strategy for those who until recently lacked the means of owning a house. Owning a house is linked to family formation and economic independence. It is also important for maintaining ties to the community. Some of those settled in California have built holiday and retirement houses in Santa Teresa. They hope to come back to the village to live close to their relatives when the time for their retirement comes. A large body of empirical literature has discussed the relationship between migration and house building (Cohen 2011; Hein 2006; Massey et al. 1987; Parrado 2004); few have discussed how it affects land use and land tenure (e.g. Zoomers 2010). In Santa Teresa, house building is taking some agricultural land out of production in a rather irreversible way. The dimension of the phenomenon however, does not indicate that this land-use change might compromise agriculture, and especially food production, in the locality. There is more area cultivated with coffee and less area of forest now than in the past. The area with agriculture and cattle decreased in the period 1990-2000 (-484 ha.) to make room for coffee. There was a slight recovery of forest area in the period 2000-2006 (372 ha). Land-use/land-cover change is dynamic, and in short periods of time some forest recovery can be observed (Jokisch and Lair 2002), although this is better understood within the dynamics of agricultural production (Fairhead and Leach 1996) (Table 1 and Figure 1). Sugarcane cultivation and cattle ranching are carried out on small scale in Santa Teresa. Both activities together with maize production have persisted since the 1800s. Agricultural production is adjusted to the biophysical features of the landscape, and to the potential income households can generate with the combination of different crops and available household labour (Figure 1). European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 93, October 2012 | 31 Table 1: Land use and land cover in Santa Teresa and its area of influence (1990-2010) in hectares Year Forest Agriculture and cattle Agroforestry (coffee) 1990 2000 2006 Total area (44,803 ha) 9,694 10,067 19,949 19,542 15,159 15,195 10,575 20,434 13,626 2010 change 9,020 20,370 15,414 - 1,556 - 64 1,787 The area in this study comprises Santa Teresa and its area of influence where some of my interviewees have their plots. Coffee is cultivated mainly in higher-altitude plots, where biophysical conditions are favourable. These plots were previously forested areas, milpa, or fallow areas resulting from the abandonment of cattle ranching. Figure 1: Timeline showing changes in agricultural production in Santa Teresa. The main cash crop is presented in italics. ~1800 sugarcane, wheat, maize-beans, cattle, fallows, forest 1970-1990 sugarcane, maizebeans, tobacco, coffee, fallows, cattle, forest 1950-1970 sugarcane, maize-beans, potatoes, cattle, fallows, forest 1990- sugarcane, maize-beans, coffee, cattle, fallows, forest Sixty-one per cent of the respondents to the questionnaire have access to or own at least one plot of agricultural land. Of those, 63 per cent have access to or own at least one hectare of land, 21 per cent between one and three hectares of land, and 16 per cent more than three hectares. In all categories of land size, migrants are more frequently represented (Table 2). Fifty-two per cent of migrant households report that they did not own any land before migrating. Table 2: Size of agricultural properties and crops cultivated in Santa Teresa < 1 ha 1-3 ha > 3 ha Only maize Only coffee Maize and coffee Only beans Maize and beans Maize, coffee, beans Other crops NonMigrant without Migrant with migrant remittances remittances Size of agricultural property (% of households) (n=100) 27 1 34 4 3 14 1 0 14 Agricultural crops (% of households) 42 100 19 12 28 15 19 4 2 23 19 4 12 0 2 Total 63 21 16 31 21 18 2 19 8 1 32 | Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 93, octubre de 2012 How being a member of the cooperative facilitates access to land For the Esperanza cooperative and for the people of Santa Teresa, the coffee crisis resulted in severe losses and poverty, but also new opportunities and challenges. The failure to renew the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) in 1989, and the entry into the coffee market of new producer countries, resulted in a historic fall in international coffee prices. This had devastating consequences for small coffee producers worldwide (Daviron and Ponte 2005). The price paid to Guatemala’s producers in 1990 was US$ 0.55 per pound, falling to US$ 0.40 per pound in 1992 (Daviron and Ponte 2005; ICO 2011). In addition to the economic losses resulting from their role as intermediaries, large landowners in Santa Teresa had to face their own losses as coffee producers and were forced to sell portions of their land to pay off their debts. The cooperative bought the land and later sold it as urban plots. Migrant and non-migrant households who are members of the cooperative were in a better position to buy this land. Membership in the cooperative secures access to information about land availability. Members also supported with their votes the decision of the cooperative to buy the land. Cooperative members could apply for credit for buying land and in this way adjust to fluctuations in the amount of money remitted and to other priorities in the household. Migrants in California are also members of the cooperative and can use their membership to acquire land. Fifty per cent of migrant households in the survey were associated with the cooperative. Fifty-four per cent of the respondents to the survey owned land. Of those, 70 per cent bought the land from the cooperative or with credit obtained from the cooperative. Forty-seven per cent of these were households with migrants. Remittances sent from California have also played a role in strengthening the cooperative, allowing it to increase its lending capacity. Since 2006 Esperanza has been involved in transferring remittances to Santa Teresa through its alliances with two Guatemalan banks: Banco Industrial, the largest in the country, and Banco G y T. The increasingly important role played by remittances in the economy of the country, and the situation of many migrants in the USA,5 has fostered alliances between Money-Transfer Operators (MTO) in the USA and banks in Guatemala (Cheikhrouhou et al. 2006). MTOs in the USA have been extremely creative in reaching senders and beneficiaries. These operators have large networks of agents in the USA but especially in states with high concentration of migrants, like California. Increasingly, rural credit and savings cooperatives are getting involved in remittance transfers. These organizations are close to the places of origin of migrants, where traditional banks are usually absent. This alternative is also cheaper and safer than other options. Structural changes in Guatemala also contributed to securing the position of the cooperative. Neoliberal reforms implemented in the 1990s introduced a series of changes in the economy of Guatemala (Gwynne and Kay 2000; Segovia 2004), and state-owned organizations were sold or transformed. During the transition, only one private bank, Bank of Coffee (BANCAFE), was operating in the municipal capital of Santa Rosa. In 2006 this bank went bankrupt and people transferred their savings to the cooperative. Once the cooperative became involved in money transfers from the US, the flow of money rose to approximately US$ 4 million between European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 93, October 2012 | 33 2007 and 2010. The number of associates in the cooperative grew from 695 in 2003 to 3,003 in 2010. This has been accompanied by an improvement of the managerial and administrative capacities of the cooperative. The current manager has a university degree in business administration and most employees have finished a type of accountant degree in the local high-school run by the nuns. This stands in stark contrast with the past, when all the work of the cooperative was done by the board of directors or members of the committees, many of whom were illiterate. The non-religious activities organized by the Church, and the increased participation of community members in national-level organizations in the 1970s, provided support to human capital formation and the creation of a stronger yet flexible cooperative. The increase in membership incorporated cooperative members into formerly inaccessible financial services. The value of savings and credit increased respectively from US$ 236,333 and 164,688 in 2003 to US$ 1.9 million and 1.5 million in 2010. In 2010 the cooperative granted 1,150 loans. Forty-six per cent were used for agriculture-related expenses, 20.5 per cent for house improvements, and 16 per cent in commerce-related activities. The cooperative has an important role in the transformation of agricultural production in Santa Teresa by providing the credit necessary for coffee production. The price of agricultural and urban land has increased tenfold during the last 15 years. Remittances have inflated land prices and created new patterns of inequality. Non-migrant and migrant households without remittances are to some degree excluded from the land market. The reason is not restricted to lack of economic means. Some land transactions, like those in which the cooperative is involved, happen in the locality and can be said to be ‘open’. Those lacking the money for the initial capital required to be a member of the cooperative cannot purchase land from it or obtain loans for doing so. In many other cases, land in Santa Teresa changes hands in California. When this occurs, the transactions are often entangled in a complex web of reciprocity between migrants in California and their families in Santa Teresa. Tereseños settled in California might finance the trip of relatives and friends, and those trips are paid back with land acquired from the cooperative. Being part of the migrant network secures access to resources and information not available to non-migrants. Why cultivate coffee? In 2003 the Esperanza cooperative established a committee for coffee commercialization and associated with a second-tier cooperative: the Federation of small coffee producers of Guatemala (Federación de cooperativas de pequeños productores de café de Guatemala, FEDECOCAGUA). This federation is composed of a network of 148 first-level cooperatives representing together approximately 20,000 small coffee producers in Guatemala. FEDECOCAGUA facilitates the access of first-level cooperative members to the globalized market through certification for specialty markets (fair trade, organic, rainforest alliance, Utz). FEDECOCAGUA also provides technical assistance, financing, and commercialization. It is through this second-tier cooperative that the coffee of Esperanza is exported. The national association of coffee producers, ANACAFE (a private organization), and 34 | Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 93, octubre de 2012 FEDECOCAGUA launched a series of initiatives targeted at small coffee producers in Guatemala in the 2000s. Funding was provided in part by USAID. Such initiatives aim at supporting the conversion of coffee production for eligibility in coffee-certification schemes. Through these markets, associates would receive better prices for their coffee, although they have to make changes in their farming and production practices. Consumers in the USA and Europe and their desire of ‘better coffee’ or at least a ‘different coffee’ (Fischer and Benson 2006) are in part at least, connected with changes in coffee production practices in Santa Teresa. Coffee as Rosenberry (2005) argues links consumption zones (and the people who consume coffee, with their lifestyles, desires and incomes) and production zones in Latin America and other parts of the global south (and the peasants who grew, cut or picked coffee in their own land or in the land of large land owners). Specialty coffees are included ‘in a widening spectrum of foods through which one [in the USA and Europe] can cultivate and display taste’ (Rosenberry 2005). The rise of specialty coffees is in part explained by the increasingly important role played by small roasters in the international coffee trade in the aftermath of the coffee crisis, but also by changing preferences and desires of consumers of the American middle class (Rosenberry 2005). Membership in FEDECOCAGUA and participation in ANACAFE’s activities has allowed the Esperanza cooperative to build its administrative and organizational capacity, to increase its political participation within ANACAFE and FEDECOCAGUA, and to facilitate contact with other actors. One of these actors is TechnoServe, a non-governmental organization with its base in Washington, D.C., which works for the development of business and industries in the south. In Guatemala, with funding from USAID and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), TechnoServe launched a project to foster small farmers’ participation in high value chains. The Esperanza cooperative participated in a project to develop a strategic plan for improving the quality of the coffee. During the project, the cooperative participated in a business meeting in Minneapolis, Minnesota. There they met with coffee roasters and brokers from around the world. During that meeting the coffee of Esperanza achieved second place in the quality competition, receiving a prize of US$ 5,000 and resulting in a portion of its coffee production being bought by an overseas company. For that lot the cooperative received US$ 1.50 per pound of coffee, while the price in the stock market was US$ 1.17. Although in economic terms this event was short-lasting, the cooperative got in contact with roasters in Europe. These roasters financed further improvements to the processing and stockpile plant recently bought by the cooperative. It has since been in a better position to buy coffee from its associates. In 2003 the cooperative bought 572,900 pounds of coffee, and in 2009 it bought 4.9 million pounds. The number of coffee producers associated with the cooperative increased from 32 in 2003 to 216 in 2009. This has also been fostered by a positive price trend in the international coffee market. Data from the International Coffee Organization indicates that the price increased from US$ 0.48 per pound in 2003 to US$ 1.09 per pound in 2009 for coffee sold in the traditional market (ICO 2011). The price of certified coffee is US$ 1.25 plus a US$ 0.10 premium per pound (FairtradeInternational 2011). Almost 90 per cent of the coffee from Esperanza was sold to niche markets in 2010. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 93, October 2012 | 35 The growth of the specialty coffee market has also resulted in new arrays of social, political and ethical concerns, in which there is a growing attention to social and environmental issues (Rosenberry 2005). This in turn is reflected by the creation of certification organizations like Fair-trade International which regulate coffee production practices and prices in Santa Teresa and other sites around the global South. Considering that agro-ecological and market conditions are favourable, it is not strange that farmers in Santa Teresa have turned to coffee production. An equally important factor is that through the cooperative’s links to larger national-level organizations (i.e. FEDECOCAGUA and ANACAFE), cooperative associates benefit from better prices. These organizations also provide agricultural extension and training, something that is highly appreciated by farmers in Santa Teresa. As a result of the structural transformation of the economy in the 1990s in Guatemala, the role of private actors and producer’s organizations in the provision of technical assistance has been enhanced (Eakin et al. 2006). The non-material dimensions of changes in land tenure and land use Owning agricultural land is clearly related to economic independence, but it also has other meanings affecting the way in which people perceive themselves and others, their environment, and their possibilities and constraints. One interviewee expressed, ‘When they [migrants] started to own the land…well we became more irreverent with those who owned the land before’. Another interviewee, a 28-yearold returnee, explained it as follows, ‘Before, they would tell you “I am a Solares”, but now, nobody tells you that. Before, they could decide if they wanted to employ you or not, how much they will pay, now it is different…now even some of them work for us. When I was a kid, people were ashamed of being poor, they were afraid of asking for their rights, and now…we are even invited to their parties!’ Owning land, which is clearly related to migration, has given the opportunity to both migrants and non-migrants in Santa Teresa to demand higher wages. Furthermore, my interviewees spoke of a new sense of equality between people in Santa Teresa, expressing for example that ‘we are more equal now’ and ‘now it is impossible to tell the difference between us [the Solares family] and them’. Interviewees often referred to changes in land tenure and the investments that migrants have made in education and housing as factors that have helped to erase ‘the difference’. By improving their access to resources (land, skills, education, health), people in Santa Teresa have also challenged power relations. This has occurred by means of the interrelation between migration and remittances and the strengthening of the cooperative. Rowlands (1997) refers to this as ‘power with’ or networking with others for joint action and change of power relations (Rowlands 1997). However, migration contributes to new inequalities where households without remittances are excluded from many of the new opportunities that households with remittances have. Lacking the money to travel to the USA or to associate with the cooperative has meant that some have to continue cultivating in rented land and working for others. Non-migrants face more problems in sending their children to school or in building houses with better sanitation services. Women whose husbands did not succeed in finding a job abroad, or whose husbands established a 36 | Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 93, octubre de 2012 new family in California (which is common), might manage to build a house; but if the inflow of remittances stops, their situation is sometimes worse than what was the case before. Acquiring new knowledge is highly appreciated by farmers in Santa Teresa. The cooperative, with support from extension technicians from ANACAFE, regularly organizes training workshops. In addition to agronomic issues, cooperative members can attend courses on how to improve their managerial capacity. They have been trained as baristas and know better how to distinguish desirable traits in their coffee. For the most part, those participating in capacity-building activities are men who cultivate coffee. Women benefit little from this type of activity. Households with remittances can afford to buy maize and cultivate it less than other households (Table 2). Decreases in maize production is affecting the pool of genetic diversity of this crop in Santa Teresa. Varieties which are no longer available or are difficult to find (for example a variety of black maize) were often described. The loss of genetic diversity also entails loss of environmental knowledge (Aguilar-Stoen et al. 2009; Steinberg and Taylor 2002). Commercial varieties of maize require higher agrochemical inputs for production, with consequences for water quality and people’s health. Increased coffee cultivation is associated with waste-management challenges. The water used to wash coffee beans and remove the coffee cherry (the fruit covering the bean) needs to be discarded, and this is usually done in the rivers. The cooperative is composting the by-products of coffee processing to make organic fertilizer and is starting a water-treatment project. However, not all coffee produced in Santa Teresa is processed by the cooperative and waste-management problems might be carried to other localities. Sixty-eight per cent of migrants with remittances use a combination of firewood and propane gas for cooking, whereas 72 per cent of non-migrants and 67 per cent of migrants without remittances rely mostly on firewood for the same purpose. This difference is explained in part by the price difference between propane and firewood. Switching to a combination of sources of fuel might reduce the pressure on trees, but it is also important for improving health conditions in the household. Conclusion Before I left Santa Teresa, Don Lencho, former president of the cooperative, told me, ‘We thought we had to go to El Petén [the agricultural frontier] to get our dream of a plot of land fulfilled…. We went to other places instead and bought our land here’. This statement captures one of the most important changes taking place in the locality during the last few years: a local process of migration-driven land redistribution. This has materialized in two ways in the landscape. The first way is the conversion of agricultural land into urban plots; the second way is the increasing importance of coffee as a cash crop in the locality. Although in Santa Teresa house building has claimed agricultural land, the magnitude of the change does not grant that it would compromise agricultural or food production. On the other hand owning a house contributes to breaking the European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 93, October 2012 | 37 cycle of poverty and inequality in which many families are trapped in poor rural areas (Parrado 2004), and this is the case in Santa Teresa. The redistribution of land from a few powerful landowners to numerous members of the community has both material and non-material dimensions. Increased engagement in coffee production has clearly had positive impacts on the income of many families. Their participation in niche markets might also have positive consequences for the environment, as shade-grown coffee production takes place in forest-like environments (Aguilar-Stoen et al. 2011), although it also entails some challenges related to water and waste treatment. Land-use decisions are no longer exclusively in the hands of a handful of people, so these challenges might be better tackled by an organization anchored in the community and with more participatory mechanisms for decision-making. It is important to mention as well that land use decisions are affected by consumers’ demand of particular products. Such consumers have desires and concerns that influence what type of coffee is going to be produced and under what conditions it is going to be produced. The people of Santa Teresa and their cooperative have been flexible in adjusting to challenges brought about by structural changes. This flexibility is in part explained by the way in which the cooperative and its members have gained access to broader networks: migrants remitting money, money-transfer operators, and coffee producers’ organizations. This access has allowed the diversification of the activities of the cooperative, including credit and savings, land purchasing, and coffee commercialization. The approach taken in this paper allowed me to explore how efforts and initiatives taking place in the 1970s resulted in human capital formation that was mobilized when new opportunities arose. Although in general the living standards of many families have improved thanks to remittances and its effects, there are still some people and family members who have not benefited from these new opportunities, notably women and poorer households without migrants. The flow of remittances and remittance practices varies over time and with the situation of the migrant (Cohen 2011), making it difficult to generalize about the causes and consequences of remittances on the receiving households and localities. My study suggests that in contexts where local organization is successful and linked to actors and networks at various scales, transnational households are in a good position to negotiate the outcomes of the use of remittances, improving their living standards without degrading the environment irreversibly. Shade-grown coffee production is less environmentally harmful than other agricultural practices, e.g. extensive cattle ranching. Non-migrant households have also benefited from the strengthening in local organization as long as they too are members of the cooperative and participate in its benefits. *** Mariel Aguilar-Støen is a Senior Researcher at the Centre for Development and the Environment, University of Oslo. Her research focuses on social-environmental relationships and environmental governance in Latin America. She studies the impact of international migration on land tenure, land use and land use change in Mexico and Guatemala. In Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Colombia, Brazil and Guatemala, she is examining, together with other partners, how economic-based ideas to 38 | Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 93, octubre de 2012 confront deforestation (PES and REDD) create new types of alliances between governments, NGOs, donors, citizens, researchers and the private sector and how these engagements foster new forms of organization and decision making. Among her recent publications are: M. Aguilar-Støen, A. Angelsen, and S.R. Moe (2011) ‘Back to the forest: Exploring forest transitions in Candelaria Loxicha, Mexico’, Latin American Research Review 46(1): 194-216; P. Pacheco, M. Aguilar-Støen, J. Borner, A. Etter, L. Putzel, and C. M. Vera-Diaz (2011) ‘Landscape transformation in tropical Latin America: Assessing trends and policy options for REDD+’, Forests 2(1):1-29. <[email protected]> Acknowledgments: This project was financed by the Norwegian Research Council project number 193710. I would like to thank my colleagues in the project ‘Migration and Land Use Change in rural Guatemala and Mexico: Is there a forest transition? – MIRLU’, Edwin Castellanos, Matthew Taylor, and Helda Morales for stimulating discussions. I am also grateful with the people of Santa Teresa, especially with the board of the cooperative whose members helped me in understanding their locality. Thanks to Catherine Tucker for her comments to an earlier version of the paper. Finally I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers for the constructive comments. Notes 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Standard qualitative methods included interviews, focus-group discussions, meetings with organized groups, and participant observation. I conducted thirty qualitative interviews with one or several members of the household. Interviewees included migrants, returnees, and non-migrant men and women from 18 to 70 years of age. I interviewed migrants who have settled in the USA while they were visiting the town and I also visited migrants in California in their houses and workplaces. The survey covered socio-economic aspects as well as demographic aspects, education, land use, agriculture, consumption, strategies to cope with crisis, migration, remittances, and investments made by the household. The survey was conducted with the participation of 115 households. I conducted a second survey with fifty additional households to gain a better understanding of their relationship with the cooperative. To protect the identity of my interviewees, their names and the name of the locality have been changed. This is a term used in Guatemala to refer to people of mixed descent. Certificación de los títulos del sitio de Santa Rosa que obran en el archivo de tierras del supremo Gobierno, compilado a solicitud de Santiago García, Alcalde 2º, Francisco Cortez, Síndico, y Juan Galicia, Secretario de la Municipalidad de Santa Rosa. 1893. Fotocopies. Undocumented Guatemalan migrants (which are the majority) do not feel comfortable approaching banks in the USA, and US banks have not tailored their services to attract Guatemalan migrants, which has allowed greater room to other actors like MTOs (Cheikhrouhou et al. 2006). Bibliography AFEHC ‘Antonino Solares’, http://afehc-historia-centroamericana.org/index.php?action=fi_aff&id= 1725. Aguilar-Støen, M.; S. R. Moe, and S. L. Camargo-Ricalde (2009) ‘Home Gardens Sustain Crop Diversity and Improve Farm Resilience in Candelaria Loxicha, Oaxaca, Mexico’, Human Ecology, 37 (1), 55-77. Aguilar-Støen, M.; A. Angelsen, and S. R. Moe (2011) ‘BACK TO THE FOREST Exploring Forest Transitions in Candelaria Loxicha, Mexico’, Latin American Research Review, 46 (1), 194-216. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 93, October 2012 | 39 Anderson, T. P. (1988) Politics in Central America: Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua.Washington: Praeger Publishers. BANGUAT ‘Ingreso de divisas por remesas familiares’, http://www.banguat.gob.gt/inc/main.asp?aud= 1&id=33190&lang=1. Bebbington, A. (1997) ‘Social capital and rural intensification: local organizations and islands of sustainability in the rural Andes’, Geographical Journal, 163, 189-97. ––– (1999) ‘Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty’, World Development, 27 (12), 2021-44. Chapman, S.; and W. L. Wong (1990) Tobacco control in the Third World: A resource atlas. Penang Malaysia: International Organization of Consumers Unions. Cheikhrouhou, H., et al. (2006) ‘The U.S.-Guatemala remittance corridor. Understanding better the drivers of remittances intermediation’. In The World Bank (ed.) World Bank Working Paper 86; Washington. Cohen, J. H. (2011) ‘Migration, remittances and household strategies’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 40, 103-14. Conway, D.; and P .Lorah (1995) ‘Environmental protection policies in Caribbean small islands: some St. Lucian examples’, Caribbean Geography, 6 (1), 16-27. Curran, S. (2002) ‘Migration, social capital, and the environment: Considering migrant selectivity and networks in relation to coastal ecosystems’, Population and Development Review, 28, 89-125. Daviron, B.; and E. Ponte (2005) The coffee paradox. Global markets, commodity trade and the elusive promise of development. London: Zed Books. de Haan, L.; and A. Zoomers (2005) ‘Exploring the frontier of livelihoods research’, Development and Change, 36 (1), 27-47. de Haas, H. (2006) ‘Migration, remittances and regional development in Southern Morocco’, Geoforum, 37 (4), 565-80. Eakin, H.; C. Tucker, and E. Castellanos (2006) ‘Responding to the coffee crisis: a pilot study of farmers’ adaptations in Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras’, Geographical Journal, 172 (2), 156-71. Ellis, F. (2000) Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Fairhead, J.; and M. Leach (1996) Misreading the African landscape. Society and ecology in a forestsavanna mosaic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. FairtradeInternational ‘The Arabica coffee market 1989-2010: comparison of Fairtrade and New York prices’, http://www.fairtrade.org.uk/includes/documents/cm_docs/2010/a/arabica_pricechart_89_10 _aug10.pdf, accessed 18.08.2011. FAO (1994) ‘Microempresas asociativas integradas por campesinos marginados en America Central. Aspectos juridicos e institucionales. FAO (ed.), (Rome). Fischer, E. F.; and P. Benson (2006) Broccoli and desire. Global connections and Maya strugles in postwar Guatemala. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. Gauster, S.; and S. R. Isakson (2007) ‘Eliminating market distortions, perpetuating rural inequality: an evaluation of market-assisted land reform in Guatemala’, Third World Quarterly, 28 (8), 1519-36. Gray, C. (2009) ‘Rural out-migration and smallholder agriculture in the southern Ecuadorian Andes’, Population & Environment, 30 (4), 193-217. Gwynne, R. N.; and C. Kay (2000) ‘Views from the periphery: futures of neoliberalism in Latin America’, Third World Quarterly, 21 (1), 141-56. Hecht, S. B., et al. (2006) ‘Globalization, forest resurgence, and environmental politics in El Salvador’, World Development, 34 (2), 308-23. Holder, Curtis; and Gregory Chase (2011) ‘The role of remittances and decentralization of forest management in the sustainability of a municipal-communal pine forest in eastern Guatemala’, Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1-19. ICO ‘Historical Data. Prices to growers annual averages’, <http://www.ico.org/new_historical.asp? section=Statistics>. INE (2002) ‘Censo de Poblacion Guatemala’. INE (ed.), (Guatemala). IOM (2011) ‘World migration report 2011. Communicating effectively about migration’. In International Organization for Migration (ed.) Geneve, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration. 40 | Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 93, octubre de 2012 Jokisch, B. D. (2002) ‘Migration and agricultural change: The case of smallholder agriculture in highland Ecuador’, Human Ecology, 30 (4), 523-50. Jokisch, B. D.; and B. M. Lair (2002) ‘One last stand? Forests and change on Ecuador’s eastern cordillera’, Geographical Review, 92 (2), 235-56. Kull, C. A.; C. K. Ibrahim, and T. C. Meredith (2007) ‘Tropical forest transitions and globalization: Neo-liberalism, migration, tourism, and international conservation agendas’, Society & Natural Resources, 20 (8), 723-37. Lambin, E. F.; and P. Meyfroidt (2011) ‘Global land use change, economic globalization, and the looming land scarcity’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108 (9), 3465-72. Letona Zuleta, J. V.; C. Camacho Nassar, and J. A. Fernández Gamarro (2003) ‘Las tierras comunales Xincas de Guatemala’. In: FLACSO (ed.) Tierra, identidad y conflicto en Guatemala. Guatemala: FLACSO. Lyon, S. (2007) ‘Fair trade coffee and human rights in Guatemala’, Journal of Consumer Policy, 30, 241-61. Massey, D. S., et al. (1987) Return to Aztlan. The social process of international migration from western Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press. Moran-Taylor, M. J. (2008) ‘Guatemala’s Ladino and Maya migra landscapes: The tangible and intangible outcomes of migration’, Human Organization, 67 (2), 111-24. Moran-Taylor, M. J.; and M. J. Taylor (2010) ‘Land and Leña: linking transnational migration, natural resources, and the environment in Guatemala’, Population and Environment, 32 (2-3), 198-215. Morán Samayoa, H. E. ‘Dinámica macromonetaria de una crisis cambiaria: un indicador de crisis cambiaria para Guatemala’, http://www.banguat.gob.gt/inveco/notas/articulos/envolver.asp?kar chivo=1401&kdisc=si, accessed 24.08.2011. Naylor, R. L., et al. (2002) ‘Migration, markets, and mangrove resource use on Kosrae, Federated States of Micronesia’, Ambio, 31 (4), 340-50. Parrado, E. A. (2004) ‘U.S. migration, home ownership and housing quality’ In: J. Durand and D. S. Massey (eds) Crossing the border. Research from the mexican migration project. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. PNUD (2010) ‘Informe nacional de desarrollo humano 2009-2010. Guatemala’. PNUD (ed.). Guatemala. Rosenberry, W. (2005) ‘The rise of yuppie coffees and the reimagination of class in the United States’. In: J Watson and M.I. Caldwell (eds) The cultural politics of food and eating. A reader. Maine: Blackwell Publishing, 122-43. Rowlands, J. (1997) ‘Questioning Empowerment. Working with Women in Honduras’. Oxford: Oxfam. Schmook, B.; and C. Radel (2008) ‘International Labor Migration from a Tropical Development Frontier: Globalized Households and an Incipient Forest Transition’, Human Ecology, 36 (6), 891-908. Segovia, A. (2004) ‘Centroamérica después del café: el fin del modelo agroexportador tradicional y el surgimiento de un nuevo modelo’, Encuentros, 1, 5-38. Steinberg, M. K.; and M. J. Taylor (2002) ‘The impact of cultural change and political turmoil on maize culture and diversity in highland Guatemala’, Mountain Research and Development, 22 (4), 344-51. Stølen, K. A. (2007) Guatemalans in the aftermath of violence. Philadelphia: University of Pennsilvania Press. Taylor, M. J.; M. J. Moran-Taylor, and D. R. Ruiz (2006) ‘Land, ethnic, and gender change: Transnational migration and its effects on Guatemalan lives and landscapes’, Geoforum, 37 (1), 41-61. Woolcock, M.; and D. Narayan (2000) ‘Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy’, World Bank Research Observer, 15 (2), 225-49. Zoomers, Annelies (2010) ‘Globalisation and the foreignisation of space: seven processes driving the current global land grab’, Journal of Peasant Studies, 37 (2), 429-47.