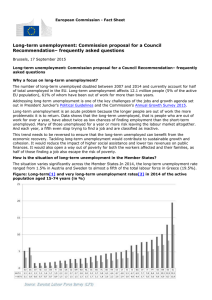

Integrated support for the long-term unemployed in Europe

Anuncio