ART. A REMARKABLE MEXICAN PAINTER. The Hour, Nueva York

Anuncio

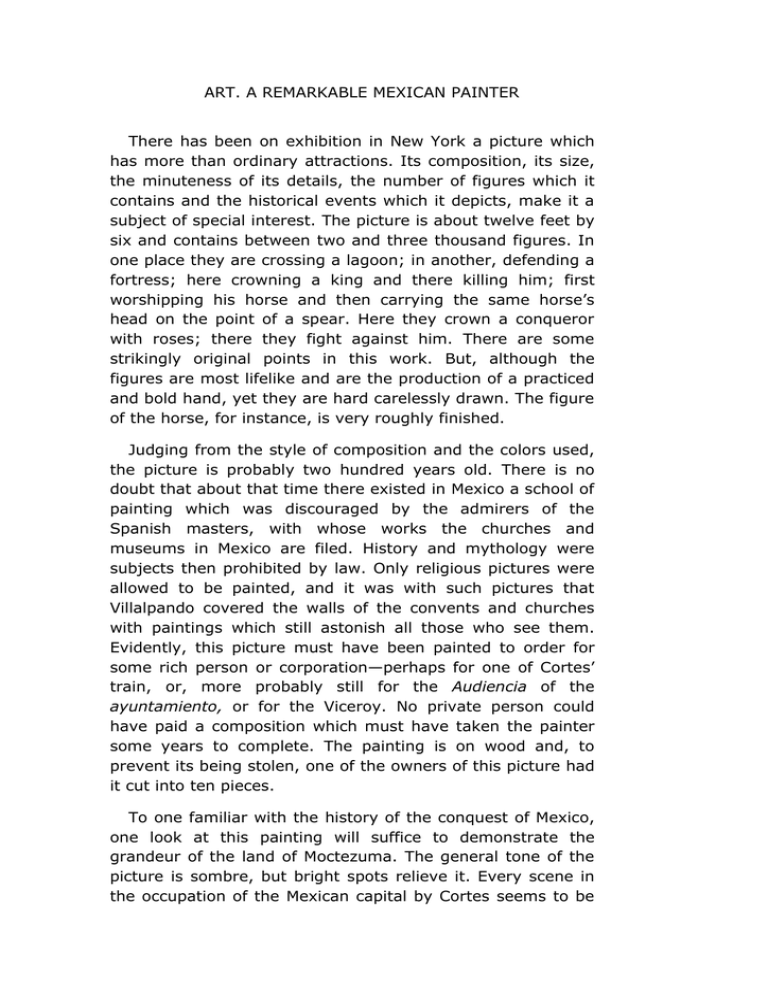

ART. A REMARKABLE MEXICAN PAINTER There has been on exhibition in New York a picture which has more than ordinary attractions. Its composition, its size, the minuteness of its details, the number of figures which it contains and the historical events which it depicts, make it a subject of special interest. The picture is about twelve feet by six and contains between two and three thousand figures. In one place they are crossing a lagoon; in another, defending a fortress; here crowning a king and there killing him; first worshipping his horse and then carrying the same horse’s head on the point of a spear. Here they crown a conqueror with roses; there they fight against him. There are some strikingly original points in this work. But, although the figures are most lifelike and are the production of a practiced and bold hand, yet they are hard carelessly drawn. The figure of the horse, for instance, is very roughly finished. Judging from the style of composition and the colors used, the picture is probably two hundred years old. There is no doubt that about that time there existed in Mexico a school of painting which was discouraged by the admirers of the Spanish masters, with whose works the churches and museums in Mexico are filed. History and mythology were subjects then prohibited by law. Only religious pictures were allowed to be painted, and it was with such pictures that Villalpando covered the walls of the convents and churches with paintings which still astonish all those who see them. Evidently, this picture must have been painted to order for some rich person or corporation—perhaps for one of Cortes’ train, or, more probably still for the Audiencia of the ayuntamiento, or for the Viceroy. No private person could have paid a composition which must have taken the painter some years to complete. The painting is on wood and, to prevent its being stolen, one of the owners of this picture had it cut into ten pieces. To one familiar with the history of the conquest of Mexico, one look at this painting will suffice to demonstrate the grandeur of the land of Moctezuma. The general tone of the picture is sombre, but bright spots relieve it. Every scene in the occupation of the Mexican capital by Cortes seems to be compressed in it, from his imposing entry, to the noche triste, when the inhabitants so fiercely revenged themselves upon him for his temerity. From these life-like representations the reality of those terrible days can be imagined. The battles, processions, vessels, castles, volcanoes and the blue lagoons of that period are seen in this great picture. Were it only for the truthfulness with which it represents the costumes of the inhabitants, the weapons of the Spaniards, the pomp of the emperors and the singular contrast between the two peoples facing each other—the Spaniard accoutered in steel, the native half naked—the picture would be well worth seeing. This artist’s deviation from the beaten path, his transition from slavish ideas to a free scope of the study of nature, his absolute disdain of imitation of masters or conventional colors and his contempt for the opinion of a prejudiced school, all tend to make this great painting well worth studying. The Hour, Nueva York, 14 de agosto de 1880 [Mf. en CEM] ARTE. UN NOTABLE CUADRO MEXICANO (Traducción) En Nueva York se ha estado exhibiendo un cuadro con atractivos nada corrientes. Su composición, su tamaño, la minuciosidad de sus detalles, el número de figuras que contiene y los hechos históricos que representa, lo hacen un asunto de especial interés. El cuadro tiene aproximadamente doce por seis pies y contiene de dos a tres mil figuras. En un lugar están atravesando una laguna, en otro defendiendo una fortaleza; aquí coronan un rey y allá lo están matando; primero están adorando su caballo y después están cargando a pico de lanza la cabeza de ese mismo caballo. Aquí coronan al conquistador con rosas; allá están peleando contra él. Hay algunos puntos de originalidad notable en esta obra. Pero, aunque las figuras son muy naturales y han sido pintadas por una mano avezada y audaz, sin embargo están dibujadas con dureza y descuido. La figura del caballo, por ejemplo, está muy mal acabada. Juzgando por el estilo de la composición y los colores usados, el cuadro probablemente tiene doscientos años. No hay duda ninguna de que en aquella época una escuela de pintura existía en México que fue desalentada por los admiradores de los maestros españoles, de cuyas obras están llenas las iglesias y museos de México. La historia y la mitología eran entonces asuntos prohibidos por la ley. Solamente se permitía pintar cuadros religiosos, y fue con tales cuadros que Villalpando cubrió las paredes de los conventos y las iglesias, con pinturas que todavía sorprenden a todos los que las ven. Evidentemente, este cuadro debe haber sido pintado por orden de alguna persona o entidad rica—quizás para algún acompañante de Cortés, o, lo que es aún más probable, para la Audiencia del ayuntamiento o para el virrey. Ningún particular puede haber pagado un cuadro que debe haberle tardado al pintor algunos años para terminarlo. La pintura está sobre madera y para evitar que fuese robado, uno de los dueños de este cuadro lo hizo cortar en diez pedazos. Para el conocedor de la historia de la conquista de México, una mirada al cuadro será suficiente para reconocer la grandeza de la tierra de Moctezuma. El tono general del lienzo es sombrío, atenuado por algunos claros. Cada escena de la ocupación de la capital mexicana por Cortés parece hallarse en esta obra, desde su entrada imponente hasta La Noche Triste, cuando los habitantes se vengaron tan ferozmente de su temeridad. De esta presentación tan natural, la realidad de aquellos días terribles puede imaginarse. Las batallas, las procesiones, los buques, los castillos, los volcanes y las lagunas azules de aquella época se ven en este gran cuadro. Si solo fuera por la veracidad con que pinta los trajes de la época, las armas de los españoles, la pompa de los emperadores y el contraste singular entre los dos pueblos enemigos—el español protegido por el acero, el indígena medio desnudo—el cuadro bien valdría la pena de verse. La salida del artista de los campos trillados, su transición de ideas esclavas a un estudio libre de trabas de la naturaleza, su maestros y por las tendencias todo tiende a estudiado. desdén absoluto por la imitación de los los colores convencionales y su desprecio por de una escuela de arte llena de prejuicios, hacer este gran cuadro bien digno de ser