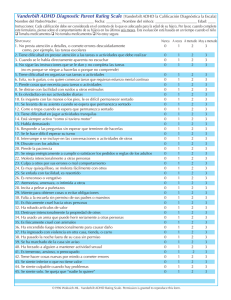

Executive Functioning and Motivation of Children with Attention

Anuncio