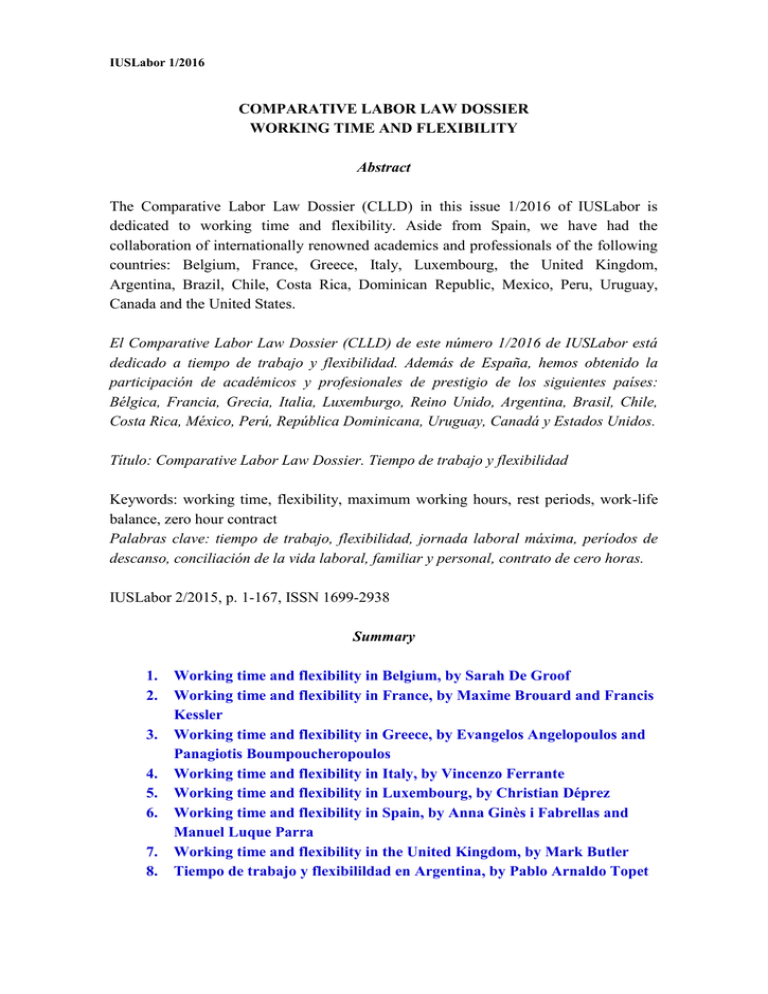

Working time and flexibility

Anuncio